People

‘Everything Is Connected’: Collector and Curator Raquel Cayre on Why There’s No Point in Differentiating Between Art and Design

Cayre spoke to Artnet News about her mission to change the way we think about art and design.

Cayre spoke to Artnet News about her mission to change the way we think about art and design.

Noor Brara

The Tomorrowists is a four-part interview series with young art world innovators who are hoping to shake up the art industry with cutting-edge initiatives and projects.

The curator, collector, and advisor Raquel Cayre, 29, has long viewed the art and design worlds as one in the same—two spheres whose differences are superficial, bound by the fact that they share the power to stir the soul through the eyes of the beholder.

In the years since starting her Instagram account @ettoresotsass—which began as a love letter to Sotsass, the founder of the Memphis Milano movement, whose work Cayre has come to collect herself—the young design aficionado has carved out a place of her own in the industry, earning the attention of such design heavyweights as Kelly Wearstler and Sotsass’s widow, Barbara Radice.

Beyond her personal collecting and social media presence, Cayre is also developing a series of projects that aim to offer audiences novel ways to experience design. For her monthlong design exhibition “Raquel’s Dream House,” she took over a New York City townhouse to create a distinctly domestic-feeling display; in “Chairs Beyond Right & Wrong,” she teamed up with R & Company to present 50 chairs from famous designers around the globe, encouraging audiences to consider them more as art than functional design.

Cayre’s latest endeavor, Open Source, is an online platform that showcases an individual artist or designer’s work that is then sold via her online shop.

Last week, we spoke to Cayre about how she fell in love with art and design, why she loves Sotsass so much, and what the design world might look like in 10 years.

Tell me a little about your background. How did you come to fall in love with art and design?

Lots of travel, books, and museums, and connecting with the right people in the field. I guess I’m an autodidact. I draw from direct experiences. When I was still a student, I took a year off from university to travel. One trip to Milan and boom! Everything changed.

I think it’s fair to say you are one of the foremost young collectors and appreciators of Ettore Sottsass and an expert on the Memphis Milano movement more generally. How did you become interested in this period and work?

I fell into Memphis Milano by chance, and with some luck. I first encountered Ettore’s earlier works (1955–69) in Milan and was attracted to his use of natural materials: rosewood, walnut, bronze, and terracotta. With Memphis, it was the plastics and laminates in bright colors and pattern that drew me in. I bought every out-of-print book on Sottsass I could find and really nerded out. I fell in love with his work and design process as a whole. His output wasn’t limited to just Memphis… it pushed outward into other disciplines.

What, in your view, distinguishes great design from good design?

László Moholy-Nagy describes the project for design as “seeing everything in relationships.” Great design is seeing relationships disappear.

Cayre’s first acquisition, a work by Cory Arcangel. Photo courtesy Raquel Cayre.

Let’s focus a little more specifically on how you began collecting. What was the first piece you got, and what’s the story behind how you came to acquire it?

In 2014, I stumbled into Cory Arcangel’s exhibition “tl;dr” (that red-carpet install!) at Team gallery, where he was presenting works from his “Lakes” series. As sculpture, these consist of flatscreen televisions turned on their sides, displaying images with the Java applet “lake” overlaid. I knew I wanted to live with the lake of Larry David and Skrillex—two opposite worlds colliding, which is something Cory was activating with the material and dated graphics in the work too.

How did that initial acquisition grow into a collection?

Everything is connected. A collection is about making these connections visible. Like design, it’s about seeing relationships. I am always re-examining traditional methods of presenting, viewing, and experiencing art as much as its corresponding mode of display.

What are some lessons you learned in bringing all these pieces together?

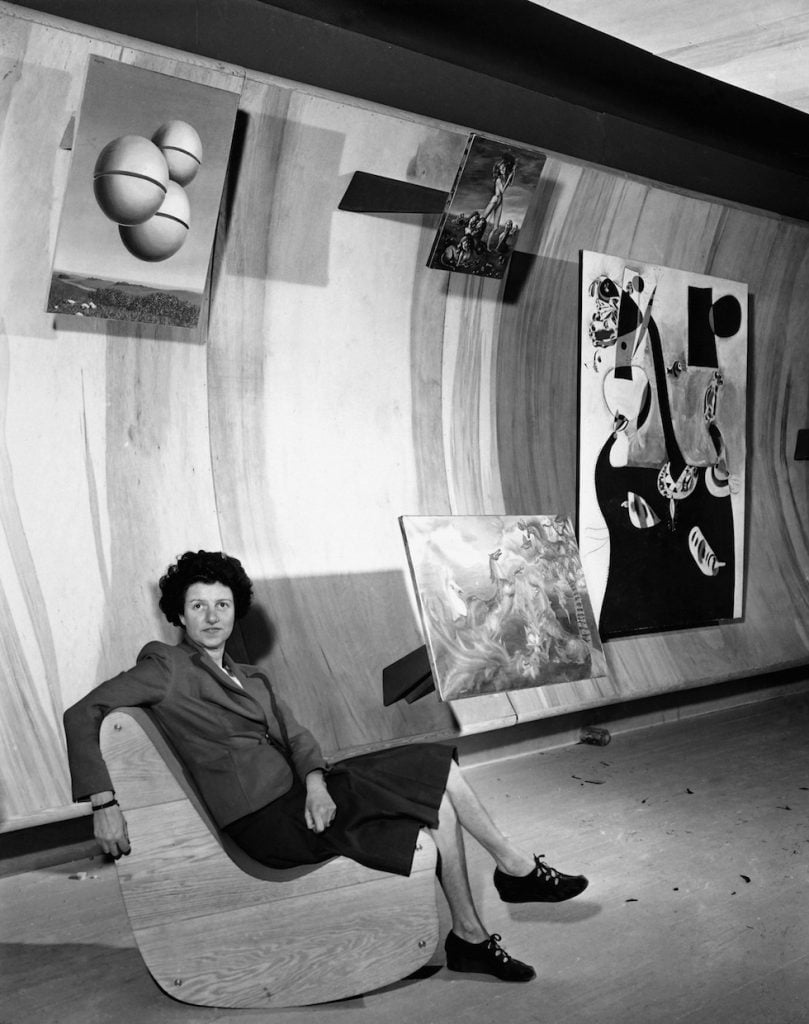

I’ve been thinking a lot about Peggy Guggenheim’s experimental gallery, Art of the Century. She’s a great inspiration for someone who wants to learn about the rules of collecting by abolishing them. She translated the act of collecting into a way of life.

How do you like to display your collection? Do you have any decorating tips for aspiring design collectors or young appreciators of design?

It’s always changing. To quote some lines from Sottsass: “These objects, which sit next to each other and around people, influence not only physical conditions but also emotions… They can touch the nerves, the blood, the muscles, the eyes, and moods of their observers… There is no special difference between [art] and design. They are two different stages of invention.”

Art collector Peggy Guggenheim poses with paintings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Oct. 22, 1942. Photo courtesy Getty Images.

It seems that in recent years, design has come to be valued as art in its own right. There’s also a lot of crossover between the two fields, with many new galleries, art fairs, and shops showing art and design alongside one another. Do you think that will become the norm over time?

This really isn’t a new idea. Since the early 20th century, we’ve been thinking about interdisciplinary art practices and museums without walls. The flatness of painting has always been linked to the flatness of pages, posters, and the flattening out of different mediums and disciplines, like the flatness of an interface. There are connections forged between photography and typography or illustration and exhibition design, between decorative objects and a poem. Everything is connected.

Perhaps what has changed is the model for making these relationships more equitable, more commercial. Instead of a museum without walls, we get a museum shop without walls. The interface isn’t just about reproduction, but where taste and subjectivity are constructed. It brings equivalence to the relationship between production and reception. We are the museum.

In your view, how should we engage with design in order to try and view it in a different or more meaningful way?

I always start by asking the question: Is it productive?

What are you focused on at the moment?

Right now, I’m working on Open Source, an online initiative to present works by individual artists and designers through my website. Works are sold through the website’s online shop and focus on one artist at a time. It does not propose to rethink e-commerce or the exhibition format, but, like a laboratory or workshop, test and iterate as it develops instead. Right now, there are no [formalized] shows, programs, seasons, or space. I’m presenting works by Nikako Kanamoto and Jasmine Gutbrod next.

What do you think the design world will look like in 10 years?

Nature. Design is always coupled with relationship and context. Like music, it’s about the production of space. Design thinking traffics in experience and reconstitutes as an act of being and seeing in the world.