Raven Leilani can’t believe she’s made the New York Times bestseller list for her debut novel, Luster. “It’s been a real whirlwind,” she says of the past few months, during which her book went from one of the season’s most anticipated new releases to one of its most-purchased volumes. “I truly didn’t expect this kind of response, especially because of the moment we’re in, but also because I used to work in publishing, so I had a real, practical idea of how this generally goes,” notes Leilani, a writer and artist born and raised in New York, between the Bronx and Albany.

Luster tells the story of a 23-year-old disillusioned editorial assistant named Edie whose dreams of becoming a professional painter have been dashed by her day job at a publishing house, where she survives on a meager salary and suffers quiet, quotidian racism in a “creative” environment that is in fact overwhelmingly corporate.

Looking for an escape, she meets Eric, an older white man in an open marriage with whom she begins an exploratory, if not questionable sexual relationship. When she loses her job, she moves in with his family—including his immaculate wife Rebecca and their lonely 12-year-old daughter Akila—and, soon, her world turns upside-down.

Many of the book’s most poignant moments come not from its violent sex scenes, but from Edie’s relationship to painting, which recall Leilani’s own attempts to become a visual artist. Though she ultimately chose to pursue writing professionally, the author still paints in her spare time, often taking weeks or even months to complete a portrait.

Leilani spoke to Artnet News about the art of painting and writing, how they differ, and what it takes to hone your craft.

Before you became a writer, you wanted to pursue a career as a painter. What got you hooked on painting?

It all started with my brother, who was the first artist I knew. I saw how art fed him and I wanted that, too. He worked in illustration and went to an art school in Pittsburgh, and so growing up, I inherited his comics, the sketchbooks he didn’t want, and art supplies that were way too good for a kid. All of that forged a love of the blank page; I started with mimicry, which I think a lot of artists do. They find a style that they latch onto and they start to copycat on the page.

I also grew up steeped in anime and video games. Then in college, I’d go to Waldenbooks—back when there was a Waldenbooks—and I would get a sketchbook each week and fill it. It was the high point of the week.

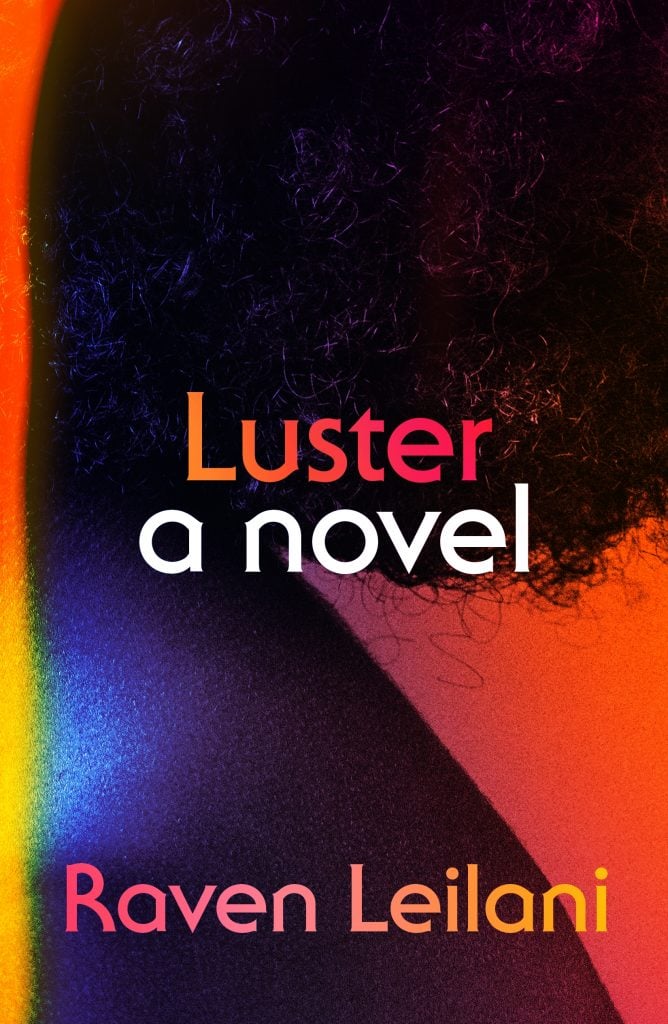

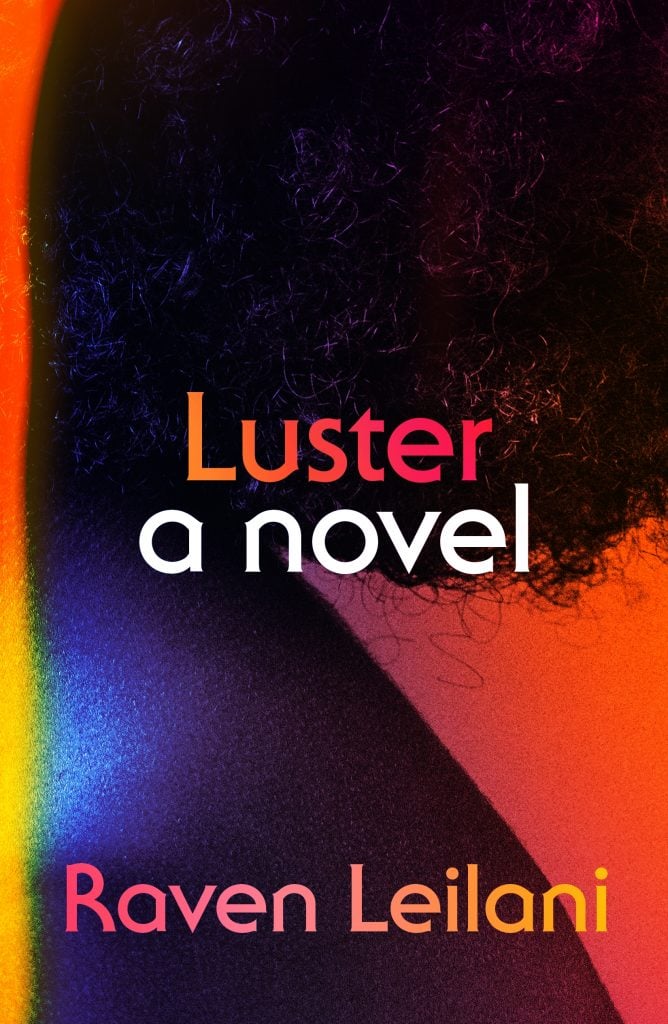

Image courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Did you intend to study art in college?

When I started making work, I was in upstate New York. My public school had a really wonderful art program. It was incredibly rigorous—the first time I tried to get in, my portfolio wasn’t fully up to snuff. We did figure drawing, art history, general illustration, and so on. It was also oriented around critique. My peers, of course, were all teenagers, but we were all serious in that way—we talked honestly and openly about what we felt was working and what wasn’t. At the time, we just thought that’s how you talked about something you made. I didn’t realize how special that was until I had distance from it.

I thought I was going to go to art school for college, but at the very last moment, I chose not to because—and I really mean this, people always think I’m being self-deprecating—you have to be practical about your skill level, especially if you want to go into art professionally. My parents and mentors were always really open and supportive, but they would also say, “You have to know that this field is competitive.” So I thought about it and I was like, “Okay, I’m maybe not quite there yet, so what I’m going to do is go to a liberal arts college that has fine-art courses” so that I could keep my options open.

I do feel validated in that because my first year in undergrad was really wonderful and atypical: they sent me and nine other students abroad to Florence, a city that’s just teeming with art. I had a teacher—a very small Italian woman with a very big voice—and she taught me how to mix color. That was the first time that I’d ever mixed anything myself using primary colors, and I realized that I could make anything from those three essentials. That opened my mind in a different way in terms of expression, as did looking at the art of the Florentine masters.

You say you were still toying around with the idea of being an artist while in Florence, during that first year of college. Did something change on that trip?

When I first got there, I had almost no respect for that kind of art. Part of that maybe came from my own inability to accurately depict the human form. When we see the human form in art, we—without trying, because we’re all human—innately understand if the proportions are right or wrong. I really struggled with those parts that were almost mathematic. There was part of me that was like, “Oh, it’s easy to replicate a human figure, but what about art that’s more about an impression, where you feel the artist’s fingerprint?” That still is my favorite kind of art, but in Florence I had a real come-to-Jesus moment about the observation and care that you need to replicate the human form. A portrait, to this day, is what I look for when I’m museum-hopping.

But in realizing all of this, I knew that I couldn’t pursue it professionally because there was just… you know, critique really orients you. It forces comparison as a matter of course. I looked at my peers and saw how capable they were. I’ve enjoyed honing my craft in private, on my own schedule. I feel I can be a little less self-conscious and that helps me be more free on the canvas. But I’m still less forgiving about my art than I am about my writing. I don’t know why that is.

Photo courtesy Evan Davis.

I wanted to ask about how you feel when you’re shifting between the roles of writer and artist. Since you touched on it, do you contend with difficulty and challenge better in your writing than in your art?

I do, in general, feel more confident and in control on the page than on the canvas. Even when it comes to being a real person in the world, I prefer the page. I can say exactly what I mean and I can take the time I need to do that.

When it comes to the canvas, I feel very much out of control. For me, painting is a process of discovery. I put down a sketch of what the thing is going to be. To be honest, the final product never adheres to that first sketch, which is weird. Sometimes my partner will come into the room—I paint in bed, like I write in bed—and I’ll say, “Please don’t look yet.” Occasionally, he’ll see the work in, say, its third iteration. And I’ll say, “Don’t tell me if you like that, because it’s going to change.”

My process is a series of mistakes that I work to correct as I’m making them. And there’s a looseness and a freeness to that that I really, really dig. When you do work about the human body, you are trying to communicate a thing that everyone is an expert on. And in making paintings, that fills me with anxiety. With writing, you’re the one who kind of summons it out of nothing. You can take liberties in a different way.

With painting and with visual art, I will always be grappling with the part that is about metrics and math. The part that’s about color and impression comes naturally. My favorite part is establishing a palette and figuring out what kind of colors I’m going to put down. But filling out the figure feels almost like an agenda—it’s drier.

Luster is about the life of a young Black female creative who is trying (sort of) to paint. How much of your own experience did you draw on for Edie? And to what extent did you pass on your art-related anxieties onto her?

There’s a clear line from me to Edie. I would say that there’s some curiosity about how much of her is me. [Laughs.] In the case of art-making anxieties, there’s a very deep parallel.

Part of that has to do with the jobs I took. When was writing this book, I was working full-time and working a couple part-time gigs, too. That frenzy bled into the pages. Even before that, during my undergrad experience, I had to balance schoolwork, needing to pay the bills, and wanting to make things on the side. In college, I painted one or two things throughout all four years. There was a senior art show, and I thought I could carve out time to do something for it. But I couldn’t.

“It” was gone for a long time and this precarious balance followed me into my adult life. I took the first job I could find. The need for that first job defined the trajectory of my work life until, basically, now. I had to send my résumé over to someone recently and there are so many jobs on the list, and they’re so disconnected.

As a young Black woman trying to achieve gainful employment, there’s less room for the less practical questions. It made the act of making things private, and sometimes it even felt delusional. That’s the thing with book stuff, too—you’re doing it in your off time and because it’s a private process that only you see, there’s an aspect of un-realness to it. You want affirmation that what you’re doing is real and good—Edie feels that. She hasn’t painted for two years. It was important for me to talk about what it looks like to move from that kind of stasis into a more generative state because that transition is really hard for a lot of artists—the ability to put a long period of not producing anything behind you.

I wanted to write about what it means to have to generate that kind of faith for yourself. But I also wanted to talk about the economic component. It was a thing that almost kept me from coming back to New York for my MFA. Edie wants to know that she has worth and she’s seeking that [affirmation] in places that will not yield real results. I’ve done that… especially with people whose co-sign you deeply, deeply want. Rebecca [the wife of Edie’s love interest] introduces a different kind of rigor to [Edie’s] work. People like that are the most important mentors—they don’t just tell you that you’re good. They push and challenge you and maybe they hurt your feelings a little bit, you know?

https://www.instagram.com/p/CCLpQ0DBqg0/

How do you feel that your process or practice as a writer has changed over the years? Do you feel that it has the value that you wanted it to have?

I can’t articulate it, because I’m still so deeply in this moment, but I feel reinvigorated and affirmed to have worked through those years that I just described and to have had those moments where I worked on things that no one saw, where I tried to have discipline in balancing work and art, and sometimes failed because you’re human and you’re tired.

There were moments where I felt very bare and stripped-down writing this [book]. I feel really, truly lucky that people are connecting with it. I had practical teachers who taught me to manage my expectations and I worked in publishing, so rejection was central to my experience with writing. It’s vulnerable to hope—but I think to make anything is really an act of hope. It’s a book that I wrote to be read. And the world met my hope, and there are almost no words for that.

At first, my writing was very much oriented inward. Everything that I felt, I spewed onto the page. The work that I did in that period is work that I’m proud of, but when I started to submit it to journals and my story would get rejected four times—four was my number—I would look at the story and think, “What could I do better?” I started to think differently about revision, about crafting a story in a way that was inviting.

The MFA program was really about figuring out—and there’s a real echo of this in visual art—that I was allergic to structure. I could feel the way that it constrained me and the rigor that I would need to meet those demands. I started looking not just at the beauty of the sentence and the thematic intent, but the way that books are put together, technically. There’s something so sexy about understanding the control behind that.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B814F5WB4Dj/

It’s funny that you say that, because in a way there are parallels to your reluctance to understand the formal elements of Florentine art when you were trying to paint—and in writing, you’ve realized that that kind of structure and technicality is not only necessary but can have, as you say, this sexiness to it. I think so many artists and writers—myself included—are like you in that we’re drawn to unbridled expression. But to cultivate and maintain rigorous, studied structure that doesn’t take away from the work’s complexity is sometimes the hardest thing.

It’s really the hardest thing. I taught briefly after I graduated the program, and I would ask students, “What are the choices that the writer is making?” We don’t necessarily have to talk about what they mean, but I just want to show you how in control this person is and why they’re doing what they’re doing. They’re putting this book together in a way that will that lead you to the next page.

When I realized that structure was not an unartistic preoccupation—that it is, in fact, a thing that would welcome a reader to my work—I felt on fire. Unbridled expression and structure—they can both exist. That’s really how I changed in terms of my craft as a writer—and what preoccupies my life as a painter.