Reviews

What Is the Real-World Value of a Left-Wing Art Show?

Our critic visits SITE Santa Fe and wonders whether biennials are ever able to truly live up to their grand ambitions.

Our critic visits SITE Santa Fe and wonders whether biennials are ever able to truly live up to their grand ambitions.

Ben Davis

“Casa Tomada,” the 2018 biennial at SITE Santa Fe in the New Mexico capital, is a jewel-box biennial.

It includes just 21 artists, spread across four galleries and a few outdoor spaces, barely larger than a large summer group show. A sense of mission will have to do the heavy lifting of welding this into something that arrests the conversation.

The show’s brief is to define “New Perspectives on the Americas.” This 2018 edition presents works spanning from Patagonia (Paz Errázuriz’s “Nomads of the Sea” portraits of the last of the Kawésqar people) to the Canadian arctic (Jamasee Pitseolak’s talismanic jade sculptures of everyday objects). It has no less than three curators: Jose Luis Blondet, Candice Hopkins, and Ruba Katrib.

As I reflect on the show, it may even be that this struggle, between the need to participate in some very big conversations and the actual capacity (and resources) to do so, makes “Casa Tomada” a particularly emblematic kind of art event for me.

The title, “Casa Tomada” (Spanish for “Occupied House” or “House Taken Over”) comes from a short story by the great Argentine fabulist Julio Cortázar. It is meant to stand for a complex network of themes that the curators want the public to discover in the show: questions about the nature of place and dispossession, who belongs and who is a foreigner.

Exterior of Site Santa Fe. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

To summarize Cortázar’s story does a disservice to its dreamlike compression, but essentially it describes upper-class siblings living in a large mansion in reclusive and contented routine. One day, they find part of the house occupied. They react by reshaping their lives around the occupation, coping with dignity—only to find the rest of the house slowly claimed by the mysterious invaders, until all their possessions are gone. At last, the siblings are ejected from the house.

Originally from 1946, the story is usually thought of as a metaphor for Argentine politics in the era of Juan Perón’s authoritarian populism. What haunts me in Cortázar’s story is the final passage, after the siblings have lost the house:

I still had my wristwatch on and saw that it was 11 P.M. I took Irene around the waist (I think she was crying) and that was how we went into the street. Before we left, I felt terrible; I locked the front door up tight and tossed the key down the sewer. It wouldn’t do to have some poor devil decide to go in and rob the house, at that hour and with the house taken over.

What Cortázar’s “Casa Tomada” is actually a parable of, it seems to me, is an establishment culture so out of touch with the social forces around it, so isolated and turned in on itself, that it doesn’t even know when it is losing. Instead of planning effective counter-measures, the siblings console themselves with a meaningless symbolic protest: to throw the house key away, so that no one can steal what has already been stolen from them.

This really does seem to me to speak to something about the predicament of culture in 2018.

Recently, at each new art opening or event where soaring statements and theoretical pronouncements denounce the evils of our moment, I wonder how I might know whether all the righteous talk is a meaningful call to action or a pantomime, complicit in exhausting political language by turning it into a detached simulacrum of itself.

Installation view of Ángela Bonadies and Juan José Olavarria, La Torre de David (2010-ongoing), documenting the residents of the Torre de David, an unfinished bank building that was taken over by squatters.

For its part, “Casa Tomada” takes up everything from the crisis in Venezuela, in Angela Bonadies and Juan Jose Olavarria’s documentary photos of the famous “Torre de David” highrise slum in Caracas, to the geopolitics of seed vaults, in Jumana Manna’s film Wild Relatives (a great work, though strangely about Norway and Syria, not the Americas).

Installation view of Jumana Manna, Wild Relatives (2018).

Biennials in general have a hortatory streak. They are meant to have the moral gravitas of civic Occasions. But today, chest-pounding moral indictment is also the bread and butter of a lot of perfectly ordinary mainstream entertainment. If culture is not about politics right now, no one is talking about it.

And that state of affairs accentuates the question of what value progressive fulminations offer in the weaker medium of exhibitions, when art no longer seems an alternative media channel but rather a small media bubble within a much larger foam.

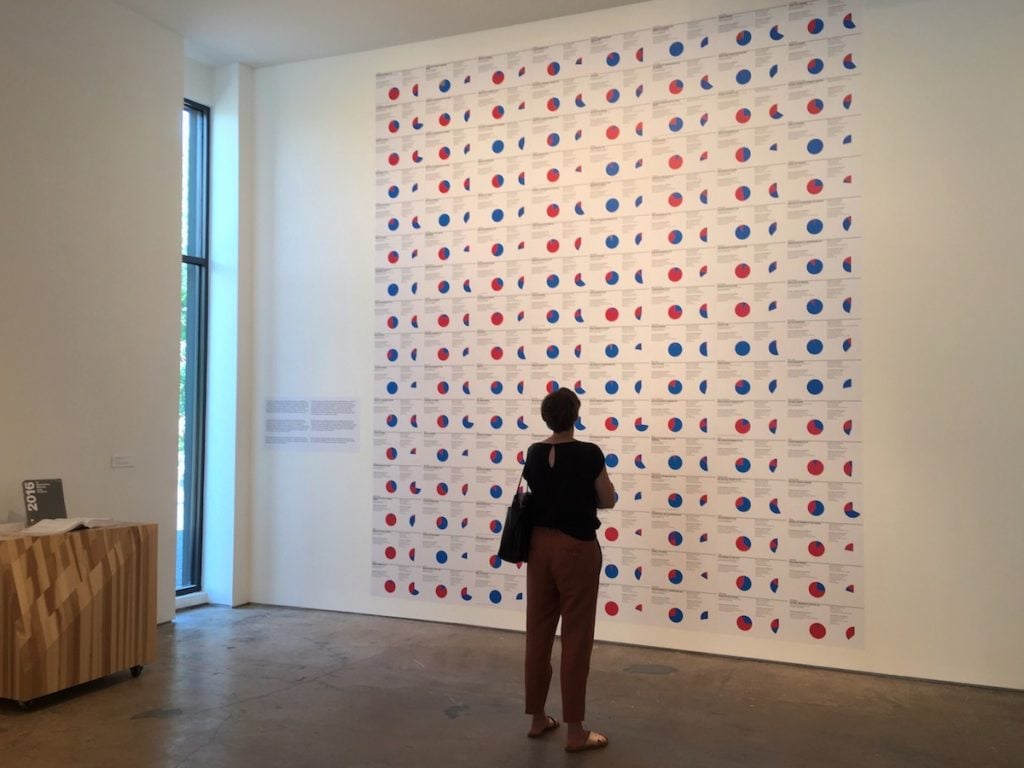

In “Casa Tomada,” this particular set of questions swells most visibly into view right at the entrance, with a major work that serves a kind of marquee function here: 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, by the well-known institutional critique artist Andrea Fraser. Essentially, it is an orderly wall mural of pie charts based on a huge research project Fraser did on the political contributions of various board members of museums across the country.

Installation view of Andrea Fraser’s 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, documenting the political contributions of board members of US museums.

Fraser’s 2016 is a tremendous work of data collection, and fascinating. She was inspired to do the work in the wake of Donald Trump’s election, when she began seeing art through the new lens of its links to unsavory Republican causes and wanted to do something about it.

And yet what it all is meant to make you feel is unclear. Rich and influential people give to museums, no surprise there: They literally have their names on the buildings. In fact, the data overall shows that the museums are more of a Democratic thing than a Republican thing. Am I supposed to be relieved?

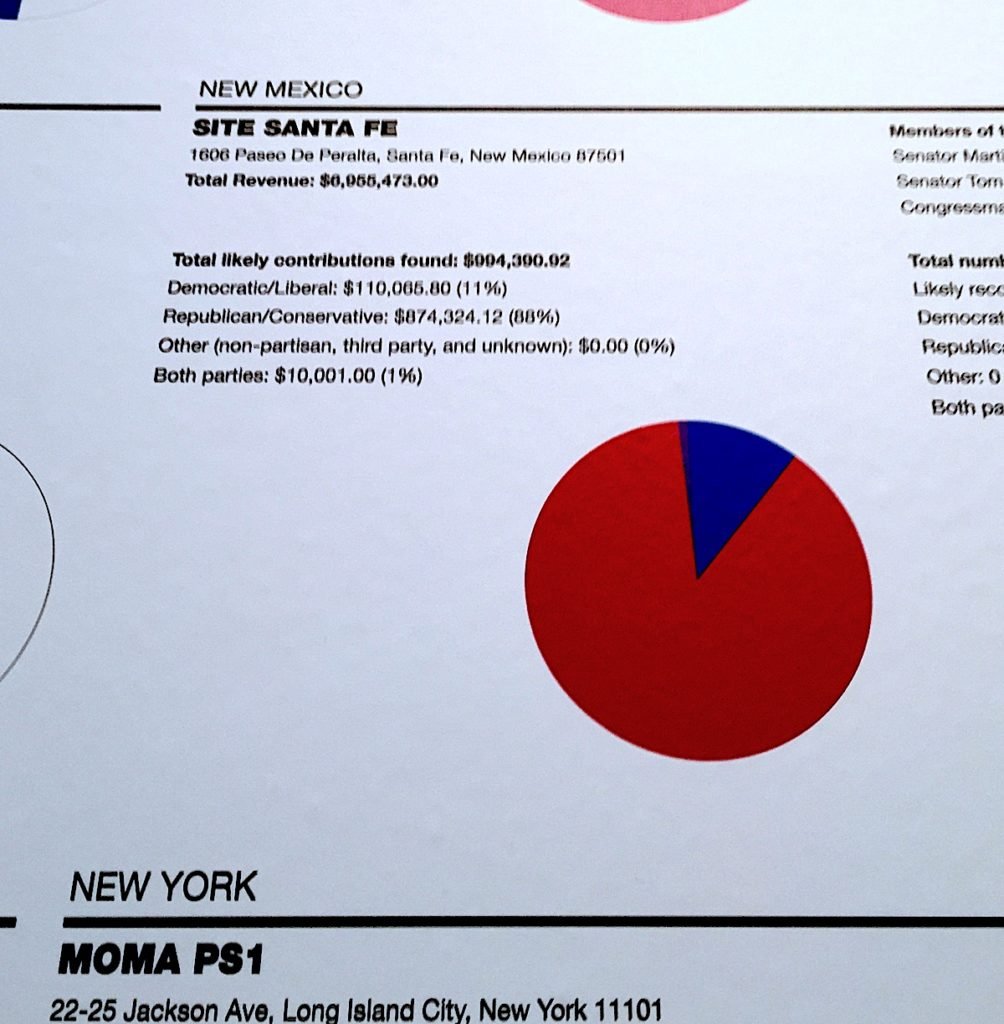

The relevant graph for SITE Santa Fe itself shows that it evidently has a staunchly Republican board. What am I supposed to do with that data?

Detail of Andrea Fraser’s installation.

Writing of the project, Fraser says that she fears it will contribute to polarization and “alienating the patrons on whose voluntary service and generosity almost all US arts organizations depend.” She even says that the project has actually increased her appreciation of their service.

“My hope is that at least some of the subjects of this study will be open to considering their roles in the political and economic context that it frames,” Fraser writes. Honestly considered, perhaps that is the ‘who’ that such a project effectively targets: not the broad public, but the affluent people who fund it.

But you could run this critique in reverse. Looking at Fraser’s pie graphs, you could say that the knowledge that a biennial as enlightened as “Casa Tomada” is linked back to money that also flows from Trump-sympathetic donors means that such agents are pre-insulated to the criticism, that there is no contradiction to be unearthed between supporting one and supporting the other, that critical art is exactly no threat to them….

I am not sure, in other words, that Fraser’s piece isn’t one of those “throwing-the-key-into-the-sewer” sorts of gestures.

I contend that Santa Fe is an interesting kind of place to reckon with such thoughts. It is a boutique enclave within a state that has the highest child poverty rate in the entire nation. The challenges of making art feel meaningful here, where the extremes are even more extreme, probably look more like the challenges of our inexorably widening divides and hyper-unequal future than those navigated by similar events on either coast.

NuMu (El Nuevo Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Guatemala), a work by artists Jessica Kairé and Stefan Benchoam), outside SITE Santa Fe. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Santa Fe is an interesting kind of art crossroads. The region has experimental-art cred as the place where figures from Judy Chicago to Lucy Lippard to Bruce Nauman have retreated to get perspective and space. It has one of the country’s largest gallery scenes, though its strengths are concentrated in craft art, the kind of stuff that contemporary art’s cerebral posture defines itself against.

It is the capital for Native arts in the country; the just-concluded Indian Market is a huge economic engine. For that matter, it has also of late become a kind of lab for what I call Big Fun Art—the artist-designed theme park attractions that are starting to multiply everywhere—via the über-popular Meow Wolf art environment, which started here and is fast expanding.

Within all this aesthetic cross-shear, Site Santa Fe is trying to make sense of itself and the present, to be spectacular but also relevant, to capture its place but to plug into the international zeitgeist.

Installation view of works by Jamasee Pitseolak. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Six years ago, SITE rebranded its signature biennial, one of the country’s oldest, to focus on the Americas (instead of on the implicitly Euro-American axis of most biennials) and wrench itself away from the sameyness of the international art circuit, dominated by celebrity curators and their stables of favorites, through its focus on collaboration. The refreshed focus has yielded an interesting mix of Latin American and Native art, making it feel genuinely as if it were opening worthwhile new channels of conversation.

But SITE’s biennials have been difficult to review in the past, I think because its mission is slightly unresolved. It’s about “the Americas,” but that is hardly a story that is possible to tell satisfyingly in the available space. It has looked to teams of multiple curators to acknowledge this scope via different perspectives, but what that ends up meaning is that it neither feels like a single subjective curatorial vision nor a coherent survey of any one geography or scene.

I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how all the various stories told by the artists fit together as a Statement, or, alternatively, where exactly the borders of one curator’s sensibility ended and another’s began. In the end, I decided that it probably does not fit together—but maybe, in the end, that reflects how the story of the Americas probably doesn’t fit together, not really, not without lines of conflict.

On the most prosaic register, my take is this: The 2018 SITE Santa Fe Biennial is difficult but pretty good!

There are definite moments that do not work. Fernanda Laguna, an important and multi-faceted Argentine artist, hangs her paintings in a paper environment that is supposed to look scrappy and alternative, but just ends up looking like not much at all.

Installation view of Fernanda Laguna in “Casa Tomada.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

But there are also works like this painting by Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun that make it all worthwhile, vibrant and full of unsettling wit.

Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Floor Opener (2013). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Nevertheless, because you have to come out of a biennial with some kind of overview, it’s tempting to focus on the works that themselves seem to thematize the difficulties of telling one story.

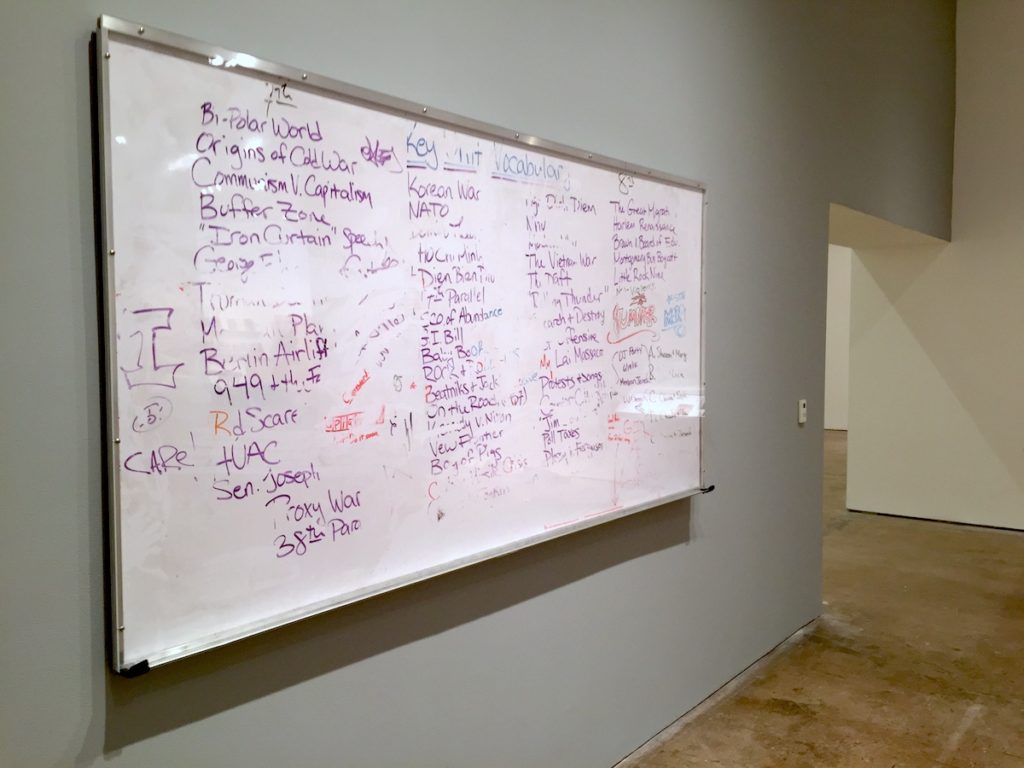

Not far from Andrea Fraser’s graphs, New York artist Lutz Bacher presents Whiteboard, a found school whiteboard, crowded with half-erased topics for a semester’s worth of Cold War History from some long-ended class: “Capitalism vs. Communism,” “Search and Destroy,” “The Great Migration.” Somewhere in there is the suggestion of a “DJ Party.”

Lutz Bacher, Whiteboard (2018).

Bacher’s blank joke seems to be how comically inadequate the available space of representation is when the crowded matters of world history try to squeeze into it. Which, translated sideways, could also be how comically inadequate something like a biennial with an educational mission is to telling the story of a hemisphere’s worth of contemporary culture.

A sculpture by Curtis Talwst Santiago.

Elsewhere, among the most compelling works on view are Curtis Talwst Santiago’s small boxes, each filled with a little diorama representing riffs on art history (an image of Manet painting Olympia) or horrors of the present (a boat at sea, laden with refugees).

The channel-surfing quality of this gallery of mini-artworks combined with their precious scale redound back onto you as a sympathetic art viewer. These fragments of history and culture feel as if they stand for the ways you are bombarded with troubling images, how you carry them with you everywhere, even as they remain remote, experienced in distanced and miniaturized form.

Victoria Mamnguqsualuk, Snake Man (1982). Image courtesy Site Santa Fe.

My favorite pieces in “Casa Tomada” might be woodblock prints by Victoria Mamnguqsualuk (1930-2016), a well-known Canadian Inuit artist. These are modestly sized, depicting mythological scenes, humans eating animals and vice versa, nature merging with humans in various ways.

I like these because of their engaging iconography—and how unconcerned they are with the context of art I know. But by the same token, I have to admit that I know next to nothing about the symbolic language Mamnguqsualuk draws on, how momentous or average these particular images are, how personal versus conventional. (I read that she is “only exceptional” because of her “renown and financial success,” but I don’t know if I believe that.)

That’s homework for me. Here, her works can only appear like the subject headings on Bacher’s whiteboard or the fragments in Santiago’s boxes.

I guess being made to feel the limits of your knowledge—of being productively particularized—may be a constructive function of a biennial like this one.

Ultimately, the key symbolic gesture of “Casa Tomada” is probably not an artwork at all.

If Cortázar’s story gives it one theme, the other bookend is provided by a sculpture of an oversize booted foot, spurs and all. This is not an artist’s gesture, but a curatorial flourish. In the 1990s, the town of Alcalde erected a bronze sculpture of Juan de Oñate, a Conquistador—indeed, sometimes remembered as “The Last Conquistador.”

Cast of the foot of a monument to Juan de Oñate, which was stolen by anonymous vandals in 1997. The act serves as a central metaphor for “Casa Tomada.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

In 1997, the statue’s right foot was hacked off and stolen in a guerrilla act of symbolic revenge. Oñate was well known for severing the feet of his own Pueblo captives.

Current debates about monuments to oppression have given the controversy around the Oñate monument new life (the vandal, evidently, still has the original foot and recently spoke to the New York Times).

The curators of “Casa Tomada” had the booted extremity recreated, and they display it here, along with a variety of the news clippings about the dispute, standing thematically for the battles over power and memory and narrative that flow uneasily through the show. In a funny way, you learn more context for this non-artwork than about most of the artworks in the show.

As society grows aware of its intensifying polarities, the question of how art relates, or does not relate, to a larger social context is only going to become more and more pressing. The charges, including from its left, that its moral claims are just self-congratulatory theater are only going to get louder. And this left critique of “art politics” at a certain point becomes isomorphic to the conservative critique of “radical chic.”

So it behooves everyone to ask themselves what they really would want from such events, positively. An art that does not question its own institutions? Just pleasing, pretty art?

Monument to Juan de Oñate at the Oñate Monument Resource and Visitors Center in Alcalde, New Mexico.

On a scorching New Mexico afternoon, I went with a herd of other art journalists to the Oñate Cultural Center, off State Road 68. In the sun and the dust, the big bronze horseman stands frozen, its foot now replaced.

At the site, the representatives of the Oñate Center explained to us, firmly, that they had decided not to tear down the monument, despite its colonialist symbolism. I gather that in New Mexico, it has its defenders. Oñate is a symbol of the Spanish roots of the area, and so of Hispanic pride asserting itself against the Anglo narrative of the West.

Caught between these forces, the Center has decided to propose its own solution: a “culture garden,” to multiply around the criminal Conquistador’s equestrian statue tributes to other diverse heroes with the hope of relativizing, decentering, and so diffusing the Oñate sculpture’s charge. But they don’t have the money for that yet; nor, indeed, do they even have the resources to tear it down and responsibly dispose of it, so they say.

Detail of the Monument to Juan de Oñate’s foot, now fixed.

Is this biennial-esque idea of multiplying and decentering stories a satisfactory solution? Probably not for fully reckoning with the past.

What I like about SITE’s boot is that it points beyond the show, out here, where the easy statement of solidarity becomes the actual problem of making solidarity happen. Maybe that’s a starting point to begin thinking art out of its bubble without giving up what it offers as a sanctuary. Weirdly, you might have to leave art’s house to move back in and inhabit it with care.