People

‘I Want Her Name to Be Remembered’: The Art World Reflects on the Life and Death of Curator Rebeccah Blum

Those close to Blum also vehemently criticized the early reporting on her death.

Those close to Blum also vehemently criticized the early reporting on her death.

Kate Brown

The Berlin-based curator Rebeccah Blum died on June 22 at the age of 53. Reports that she had been murdered by her partner sent ripples of shock and pain through the international art world. An American who spent much of her career in Germany, Blum was a multifaceted art-world professional who worked as a dealer and curator and helped develop the careers of artists including Monika Baer and Jorinde Voigt.

Last Wednesday night, Blum’s longtime partner, artist Saul Fletcher, 52, is suspected to have killed Blum in their Berlin apartment before dying by suicide himself. A police report states that an investigation into a violent murder is ongoing, as well as Fletcher’s apparent suicide in their summer home shortly thereafter.

For many close to Blum, the media coverage of her death added more pain to an already horrific tragedy. Initial reports honed in on Fletcher’s “moody” art practice and his accolades, obfuscating the brutal nature of Blum’s killing, as well as her own accomplishments.

Details of the evening are also now coming into focus. Contrary to early coverage, the now-dead suspect did not call his daughter, or Blum’s daughter, to confess; instead, he called an unrelated friend, who called the police. A source close to the family says that authorities showed up at Blum’s daughter’s door at 3 a.m. looking for Fletcher, who it seems had driven from the apartment the couple shared to Blum’s summer cabin outside the city. He was later found dead.

As the news and fallout reverberated on social media, art-world figures, friends, and family offered a counter-narrative, drawing attention to Blum’s life. “I want her name to be remembered and nobody else’s,” wrote Blum’s daughter, Emma, in an Instagram post Wednesday.

Who was Rebeccah Blum, and why wasn’t the question asked right away?

Those who knew her remember her as an intelligent, kind, and reliable person. A close friend and former roommate, Jane Rosenzweig, describes her as “present” and “curious.” Though they lived on separate continents, their lives often ran in parallel: they had kids around the same time, they got summer cabins—Blum loved her lakeside summer home in outside Berlin. Rozenszweig says they both met their partners around the same time, too.

In her professional life, Blum was an editor, publicist, coach, networker, curator, and art dealer. New York gallerist David Nolan, for whom Blum served as a European representative, said in an statement that she “was no ordinary American transplant on the Berlin art scene.” The two had met at the 2007 Venice Biennale, and the dealer recalled feeling struck by “her natural understanding of art and empathy for the underlying motivations of artists.”

Over the years, Blum introduced Nolan to several valuable talents, including Berlin-based Jorinde Voigt, whom he now represents.

Blum was born in Berkeley, California, in 1967 to Susan Bockius, an author, and Mark Blum, a professor. She studied art history in Washington, DC, before arriving in Germany in the early 1990s, where she spent years in the Düsseldorf art scene, then the beating heart of the German art world, before relocating to the still-fledgling arts hub of Berlin.

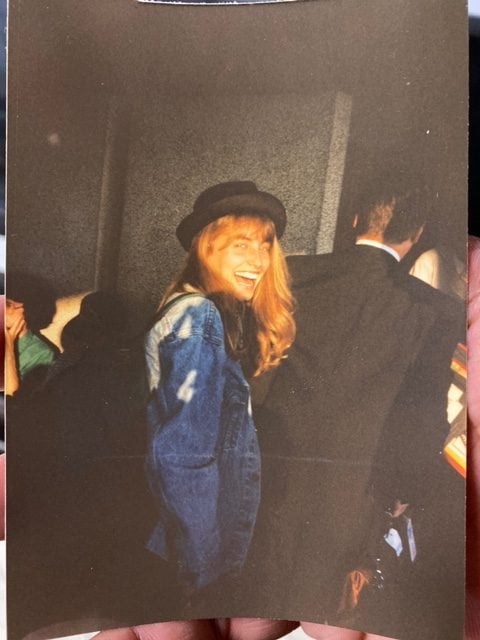

Rebeccah Blum (circa 1987). Courtesy Jane Rosenzweig.

Marie-Blanche Carlier from Berlin gallery carlier | gebauer recalls learning from a mutual friend that Blum had encouraged several artists to move from Düsseldorf to Berlin, and often hosted them in the German capital. “Rebeccah was creative, funny, generous, open-minded—one could always stay for diner she would magic something spontaneously,” Carlier told Artnet News. “She was extremely engaged, serious, and precise in her passing of knowledge about the artists she promoted while remaining friendly and full of humor.”

After moving to Berlin, she was hired by gallerist Aurel Scheibler to help helm the ScheiblerMitte project space, which organized shows of Alice Neel, Michel Auder, and others. In 2012, Blum struck out on her own, working with artists, galleries, and collectors as a project manager through her own company, Blum Fine Art Management. Two years later, she established a project space with Kit Schulte called Satellite Berlin, which focused on interdisciplinary art engaged with the humanities and sciences. “We put our heart and soul” into the project, Schulte wrote in an obituary.

Blum was also a devoted mother. “She was fully committed to provide her daughter the best context and education to grow, which is not easy while having a career,” Carlier said. She wove her love of children into Satellite Berlin; photos from 2015 show Blum working with a third-grade class at the project space.

In 2017, she shifted gears to focus on editorial work, founding the Wordsmith, a translation and editing company. Her career was poised to take yet another turn just before her death. According to Rosenzweig, Blum had just gotten her Masters of Arts degree last month. Her thesis focused on storytelling as a strategy for intercultural audience development in cultural institutions. “Rebeccah wanted to stimulate the general dialogue between art and culture in a meaningful way, and to develop new content in collaboration with other areas,” Schulte wrote in her obituary.

“Her next career chapter was just beginning,” Rosenzweig added.

‘Misogynistic’ Reports and the Taboo on Femicide

While Blum’s untimely death—which comes shortly after the UN reported in April that gender-based violence was rising in many nations, including Germany—has been mourned in the German and US art scenes, it was accompanied by a swift outcry against initial reports in the Daily Mail, ARTnews, Monopol, and others that focused on Fletcher’s accomplishments; referred to the apparent murder-suicide as a “family drama”; and detailed his luxury car and friendship with Brad Pitt.

On Wednesday, the Journal des Arts published a story titled “Who Is Saul Fletcher?” remarking that “the self-taught artist, who is said to have killed his partner, is known for his dark and melancholy photographs.”

In a Facebook post, artist Candice Breitz pointed out that “nearly every single piece of journalism covering the murder zooms in on the career achievements and art accomplishments of the Famous-Artist-Boyfriend.” She also points out that many reports avoided the term femicide. It was a sentiment echoed by swathes of social-media users; one called the coverage a “sickeningly misogynistic obfuscation.”

Many berated the art world specifically for its response. Berlin artist Julieta Aranda wrote in a post on art agenda that it “is remarkable that, in a field like contemporary art—which claims to be both adept at imagining the future and at proposing instances and avenues for social justice—it is as if no time has passed between 1985 and 2020.” The former date references artist Ana Mendieta’s death, for which her husband, artist Carl Andre, was acquitted of murder.

Some were also incensed by Fletcher’s galleries’ joint statement, which omitted the allegations of murder. “We are devastated, horrified, and shocked by the tragic loss of Rebeccah Blum and Saul Fletcher,” wrote Anton Kern Gallery in New York, Knust Kunz Gallery Editions in Munich, and Grice Bench in Los Angeles. “We are all distressed and confused. We offer our deepest condolences to their families and together we offer our support and help.” (Artnet News asked Knust Kunz and Kern to also respond to the criticisms around their statement, but did not immediately hear back.)

Members of the Berlin community also noted that, despite the wave of coverage, Fletcher was not a particularly prominent or prolific artist: his last show in the German capital appears to have been at Galerie Neu in 2008. (His dealers did not immediately respond to a request for confirmation.)

By now, many arts publications have published articles focusing on Blum’s life and accomplishments. Yet, for many, the tragic denouement is evidence that misogyny can inform even liberal and progressive factions of media.

“You should get one thing right: There was this beautiful woman and human being, a charismatic personality of the Berlin art scene getting stabbed with a knife by her psychotic and latently aggressive lover, who happens to be an artist, not a bad one,” dealer Aurel Scheibler wrote in an email to Artnet News.

“Rebeccah Blum was a mother, she was a member of our artistic community, she was a beautiful person who dearly deserves to be remembered as such,” read a joint statement from members of her professional community. “We want to recall her name, and firmly condemn the brutality that took her life away, a too well known violence that needs to stop.”