Art World

A New Exhibition Draws Back the Curtain on Rembrandt’s Theatrical Inspirations

A new exhibition at the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam reveals how theater inspired the Dutch master.

A new exhibition at the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam reveals how theater inspired the Dutch master.

Tim Brinkhof

On January 3, 1638, the Schouwburg on Amsterdam’s Keizersgracht canal opened its doors. Modeled after the Teatro Olimpico in the Italian city of Vicenza, the first public theater in the Dutch Republic attracted visitors from all walks of life. Plebs and patricians alike flocked to the venue to watch playwright Joost van Vondel’s Gijsbrecht van Aemstel, written especially for the Schouwburg’s inauguration. Also present in the crowd was painter Rembrandt van Rijn, who lived nearby and enjoyed sketching actors as they performed.

A man of means with a taste for the finer things in life, Rembrandt was an avid theatergoer. However, his interest in the art form went beyond recreation. As explained in “Directed by Rembrandt,” a new exhibition at the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam, the plays he saw greatly influenced the paintings he composed, from the colorful costumes in which he dressed his subjects to the dramatic poses they assumed.

Pen and ink study of the actor Willem Ruyters as an innkeeper with studies of two heads; ascribed to Rembrandt van Rijn. Photo: Rembrandt House Museum.

Rembrandt’s exposure to theater was not limited to the Schouwburg. He produced multiple sketches of traveling actors from England and France, who came to Amsterdam during the holiday season. He also drew quacksalvers, grifters selling dubious medicines and tonics. “Here you see a quack standing on a podium with a parrot on his shoulder,” curator Leonore van Sloten said, pointing to a pen and ink drawing from 1636. “Dressed to impress, he uses every trick in the book. This includes rhetoric, the art of storytelling and persuasion. That’s what actors do, too.”

Rembrandt van Reign, drawing of a quack (c. 1638). Photo: Albertina/Rembrandt House Museum.

Rembrandt first encountered theater in his education. Like many middle- and upper-class children in Europe at the time, his schooling revolved around the classics. He learned Latin, studied the works of prominent Roman writers and orators, and together with his classmates staged plays from ancient Greece—experiences that taught him the power of body language and facial expression.

Rembrandt approached his paintings as if they were acts of theater frozen in time and space. He posed in front of a mirror to practice drawing expressions, and would—dressed in full costume—act out a scene as if for an audience. In doing so, he not only took on his subjects’ appearance but also their emotional state, which he thought was just as crucial to the painting process.

“If you, the artist, want your painting to make me cry, you must cry first,” one of his students, Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten, later wrote—a lesson van Sloten says he likely learned from Rembrandt.

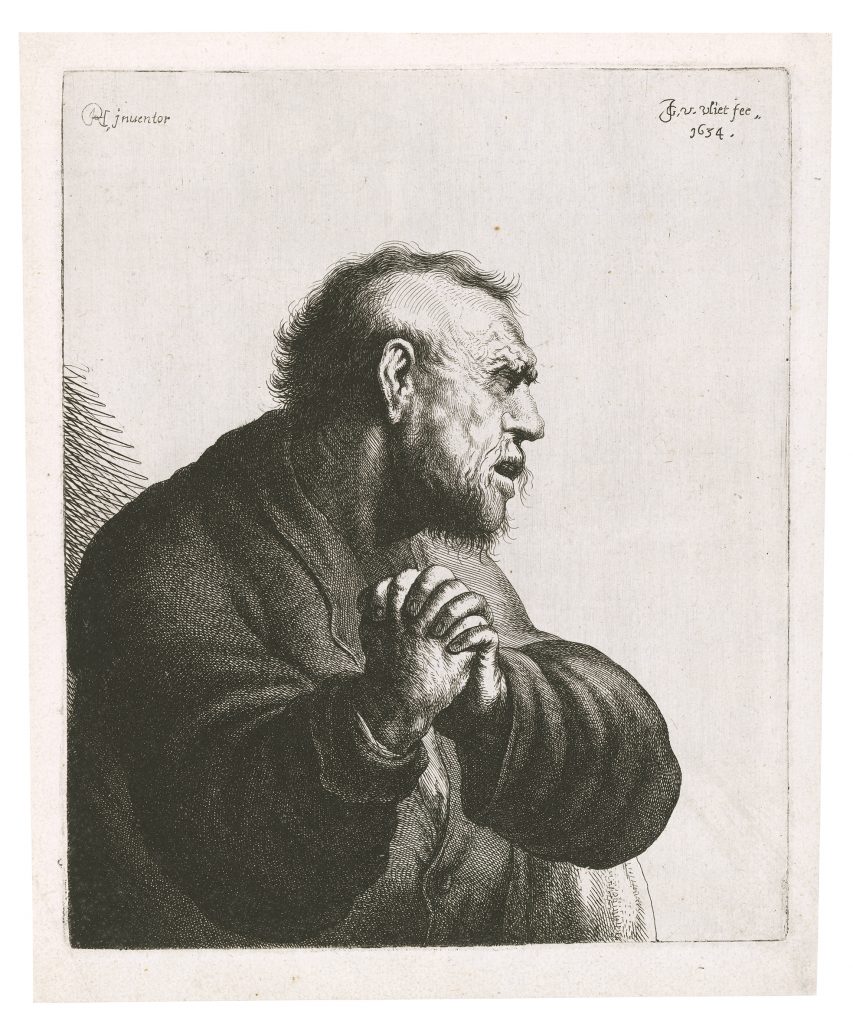

Performance was pivotal to painters, who, unlike playwrights, had to communicate stories without words or sounds. Helpful in understanding Rembrandt’s work is a 1644 book published by the British writer John Bulwer, Chirologia: or the naturall language of the hand, which explains the meaning of various hand gestures passed down from classical antiquity and therefore universal across much of 17th-century Europe. Van Sloten turns to Rembrandt’s 1629 painting Judas Repentant, Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver, which sees the betrayer of Christ give back the money he made turning in his savior, only to be refused by the Jewish high priests. “According to Bulwer’s book, Judas’ clasped hands mean, ‘I cry, and I feel pain.’” The gesture communicates what is also shown in the subject’s face, which is covered with blood from the hair Judas tore off his own head.

Jan van Vliet, etching after Rembrandt’s The Repentant Judas (1634). Photo: Rembrandt House Museum.

Another painting in the exhibition, Potiphar’s Wife Accuses Joseph (1655), shows the wife, named Zuleika in the Koran, placing one hand over her heart while raising the other, a gesture people made when they were stating something factual and which, in this case, is supposed to give an air of credibility to her lie. (After failing to seduce Joseph, she falsely accuses him of attempting to violate her.) A similar gesture is used in The Night Watch by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, who appears to be in discussion with his lieutenant.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Potiphar’s Wife Accuses Joseph (1655). Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin/Rembrandt House Museum.

Narrative in Rembrandt’s paintings follows the same rules as it does in ancient plays. “If you want to tell a story,” explained van Sloten, “you start by choosing which moment in the story you want to depict. One important moment that has been described since antiquity, and without which a play was considered incomplete, is peripeteia: the turning point where everything changes. Peripeteia is often preceded by anagnorisis or revelation, the moment the truth is revealed to be different than initially expected.”

Rembrandt painted anagnorisis in Haman and Ahasuerus at the Feast of Esther (1660), which depicts Esther in the moment she is about to tell her husband, who is hearing a proposition to kill all Jews under his rule, that she herself is Jewish. Even more delicate is Rembrandt’s treatment of the central character in Susanna (1636). In the Bible, she is about to go bathing when two men tell her that, if she refuses to have sex with them, they will tell her husband she cheated on him: a capital offense. Here, Rembrandt has painted Susanna in the act of turning from the water to the men hiding in the bushes behind her. As her head turns, her eyes meet those of the viewer, involving them in the scene the same way an actor would sometimes involve their audience.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Susanna (1636). Photo: Mauritshuis/Rembrandt House Museum.

“Directed by Rembrandt” is on view at the Rembrandt House Museum, Jodenbreestraat 4, 1011 NK Amsterdam, Netherlands, through May 26, 2024.