Art & Exhibitions

A Look at 5 Key Renaissance Masterpieces on View at Buckingham Palace

“Drawing the Italian Renaissance” opened on November 1, emphasising the importance of drawing as an artform in its own right.

“Drawing the Italian Renaissance” opened on November 1, emphasising the importance of drawing as an artform in its own right.

Verity Babbs

At Buckingham Palace’s King’s Gallery, is a show of Italian Renaissance royalty. “Drawing the Italian Renaissance” is filled with masterpieces from the epoch by some of the most famous artists who have ever lived.

The exhibition, containing around 160 works made between 1450 and 1600 (more than 30 of which are making their public exhibition debut), aims to reframe the significance of drawing for Renaissance masters. Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian are on view in a show that exemplifies the exquisite and layered history of drawing during the Italian Renaissance. The artworks all come from the Royal Collection, belonging to the British crown, which has one of the world’s largest collections of Renaissance drawings.

Long believed to simply be part of the drafting process, the curators at the King’s Gallery are now highlighting the importance of drawings as finished artworks in their own right, showcasing their individual beauty.

Here is the backstory behind five key Renaissance masterpieces now on display at Buckingham Palace.

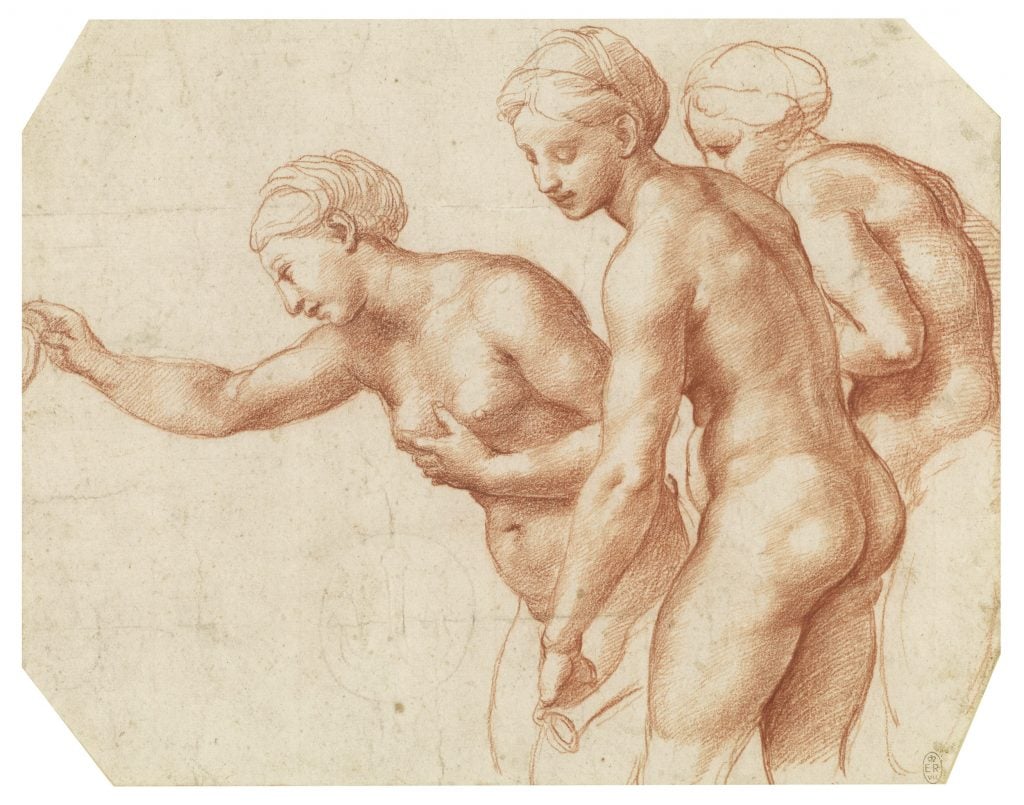

Raphael, The Three Graces, c. 1517-18

Raphael, The Three Graces, c.1517–18. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

Raphael created The Three Graces as a preparatory chalk study for a fresco in Rome’s Villa Farnesina, the suburban villa built in 1506 for Agostino Chigi, the banker of Pope Julius II. The study shows one model in three poses, and Raphael was one of very few artists of his day to work directly with a nude female model. The fresco, the Wedding Feast of Cupid and Psyche, shows the marriage festivities of the Roman god of love and goddess of the soul. In attendance are the Graces—three daughters of the king of the gods, Jupiter—Euphrosyne, Aglaia, and Thalia. While the fresco (one of two) was executed by the artist’s assistants (the works were met with criticism following their sloppy execution), this preparatory study was done by the artist’s own hand. Offsets, images created by transferring a pre-existing image onto a new canvas or page, were made of many of the drawings Raphael prepared for the Villa Farnesina frescoes, and damage is visible to the upper right-hand corner where damp paper was applied to the chalk.

Michelangelo, The Virgin and Child with the Young St John, c. 1532

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Virgin and Child with the young Baptist, c.1532. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

No one is entirely certain about the reason why Michelangelo created this black chalk drawing as it does not directly correlate to another sculpted or painted project completed by the master. This may suggest that the drawing was designed as a completed work in its own right, and it is done in delicate detail. Perhaps it formed part of Michelangelo’s private religious practice. There is pentimenti, evidence of earlier marks which the artist has drawn over and re-shaped, as well as evidence of the time and dedication Michelangelo took to end up with his final design. On the reverse of the drawing is another design, this time of a single figure, but it is not believed to have been created by Michelangelo. It has been speculated that Michelangelo created the drawing for another artist to use it as a model for a sculptural group.

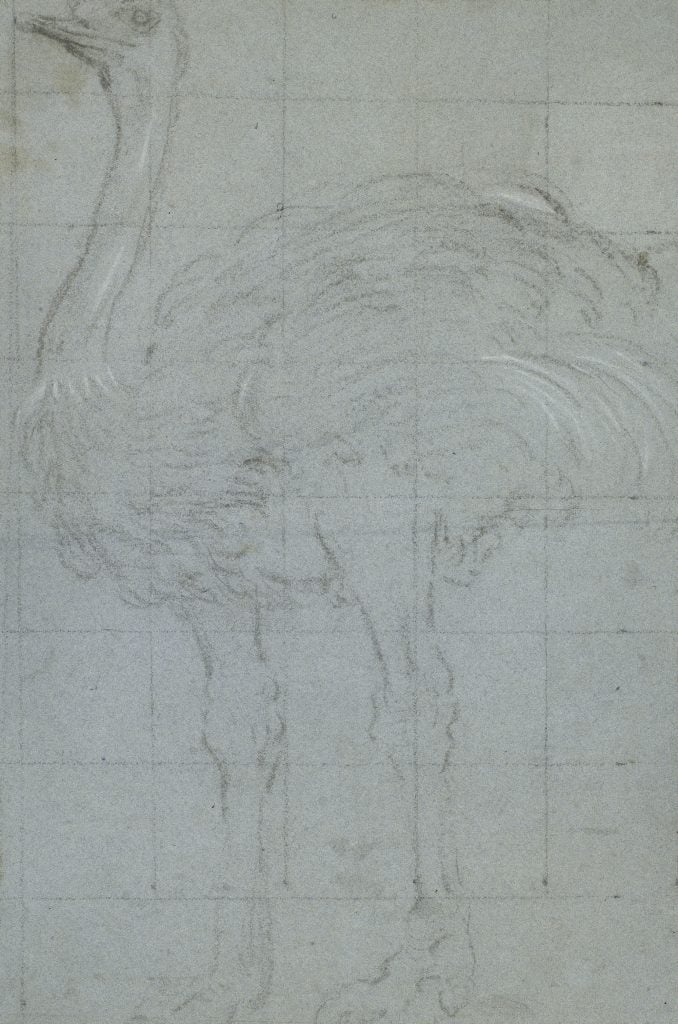

Att. Titian, Ostrich, c.1550

Attributed to Titian, An ostrich, c.1550. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

Native to Africa, it would have been rare for an Italian to have seen a living ostrich. However, the detail and convincingness of the proportions of this drawing, attributed to Titian, suggest that it was drawn from life, or certainly based on real exposure to the flightless bird. Ostriches had been imported to the Italian port of Venice—one of the most powerful trading cities in the world at that time where Titian spent the majority of his life, dying there in 1576. The drawing was cut down to reduce its borders so that the depiction could be transferred, although the location of the final artwork which was the result of this process—and whether it survives at all—is unknown. The Flemish baroque Anthony van Dyck made a copy of the drawing in his “Italian Sketchbook” which he made while visiting Italy in the 1620s.

Alessandro Allori, Fortitude, Prudence and Vigilance, c. 1578

Alessandro Allori, A design for an overdoor with Virtues, c.1578. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

Allori, a painter who was born in Florence in 1535, created this study for a commission by Francesco de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. The design, painted as a fresco at the Villa Medici at Poggio a Caiano, shows three of the embodiments of the virtues: Fortitude, defeating a dragon and holding a lion by its head; Prudence, who sits upon a world globe with a mirror and serpent; and Vigilance, who stands on top of a set of military trophies holding a small sun above her head. These motifs were chosen to symbolize the power of the Medici, a powerful banking and military family who ruled Florence for almost 300 years between the 15th and 18th centuries. The fresco for the Salone di Leo X was Allori’s largest secular project, and this drawing was a study for an overdoor. The decoration of the Salone was abandoned in 1521 just a year after it began, after Pope Leo X died unexpectedly from pneumonia, and 57 years later Allori was commissioned to finally complete it.

Leonardo, A Costume Study for a Masque, c. 1580

Leonardo da Vinci, A costume study for a masque, c.1517–18. © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2024 | Royal Collection Trust.

In 1516 Leonardo moved to France aged 64 to live and work in the French court of King Francis I. While there, one of his duties was to design costumes for festivals and events, and this study shows his skill at intricate design and capturing the effects of draped fabric in his drawings. This study is completed in such detail that it was likely given directly to royal seamstresses to create the final costumes from it. Several costume drawings made by the Renaissance polymath survive from the end of his career. Masques—entertainment popular with the aristocracy in France and England during the 16th century—involved song, dance, and the performance of plays, with party-goers wearing disguises. Not designed to be practical, this young man holds a lance and wears bearly-there breeches.