If the newly renovated National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, D.C., feels something like hallowed ground, that could be due in part to the building’s history: Built in 1908, it served for the first 80-odd years of its existence as a Masonic Temple.

But while women were barred from entry in those days, since 1987 have had their run of the building. That’s when it was reborn as the world’s first and only major museum dedicated exclusively to women artists. (Today, its mission to combat gender-based discrimination in the arts has expanded to embrace nonbinary and transgender individuals.)

NMWA was the brainchild of Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, who with her husband Wallace Holladay, became a dedicated collector of women’s art. When she started, this field was criminally under-recognized—infamously, Janson’s History of Art, the field’s standard text book, did not include a single work by a woman. But that also meant that women’s work was a bargain compared to that of their male counterparts.

The institution opened in 1987 with just 500 works. In the decades since, it has grown to 6,000, and the museum has hosted over 300 exhibitions, including solo shows for Spanish Surrealist Remedios Varo, African American painter Loïs Mailou Jones, and American photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe.

National Museum of Women in the Arts founder Wilhelmina Holladay and Barbara Bush at the ribbon cutting for its opening on April 7, 1987. Photo by Stephen Payne, courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.

This weekend marks NMWA’s reopening following a renovation that began in August 2021 (just a few months after Holladay’s death at 98). It adds 15 percent more exhibition space to the landmarked building, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. The rehung galleries allow the museum to showcase new acquisitions as well as pieces from its holdings that have previously languished in storage—a full 40 percent of the current installation is on view at NMWA for the very first time.

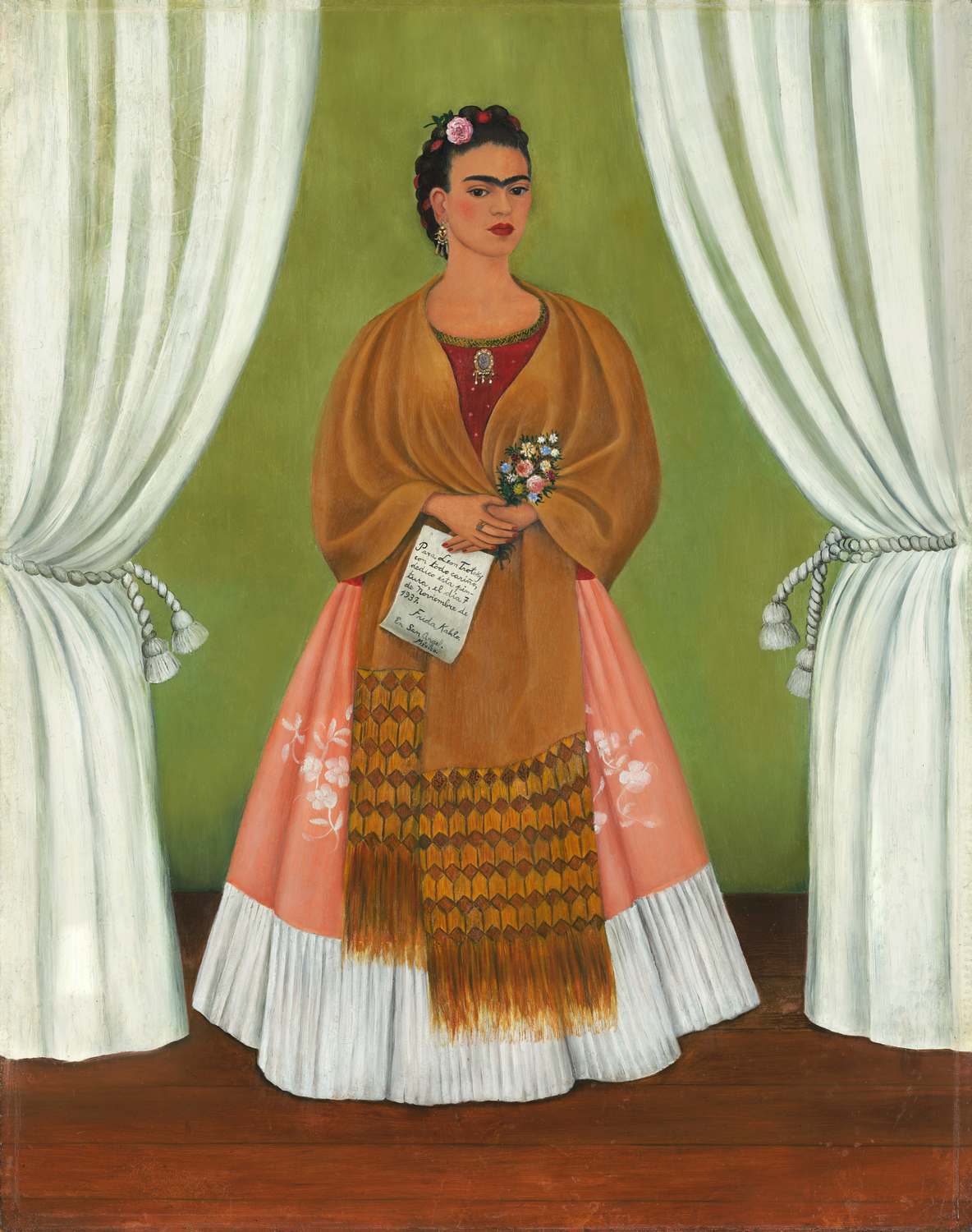

It’s a collection that boasts some undeniable art historical masterpieces, including D.C.’s only Frida Kahlo, prominently on display in the mezzanine level up a marble staircase just beyond the entrance. She’s paired with other portraits and self-portraits of women, both historic and contemporary, from 19th-century French Impressionist Eva Gonzalès to present-day South African photographer Zanele Muholi.

The bulk of NMWA’s holdings date to the 20th century—think names like Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Faith Ringgold, Judy Chicago, and Cindy Sherman. But a pair of 16th-century Lavinia Fontana works mean that the institution’s presentation of women’s art history stretches back to Renaissance Italy, a time when the arts were even more male-dominated than they are today.

The newly renovated National Museum of Women in the Arts, exterior, 13th Street and New York Avenue sides. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

“Despite lip service that everything is changing, gender inequity in the arts continues, making our advocacy more important than ever,” Winton S. Holladay, the founder’s daughter-in-law and chair of the museum’s board, said at the press preview. (In the run-up to its reopening, museum leadership has cited depressing statistics from the 2022 Burns Halperin Report, which made clear how the art world continues to under-represent women and Black artists.)

For an art journalist and critic who has spent years eagerly hunting down the rare work by women at major art museums in countries around world, carefully writing down their unfamiliar names and snapping photographs for future research, I found walking through the NMWA galleries something of a revelation.

Collection galleries at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Photo by Jennifer Hughes, courtesy of NMWA.

Yes, our encyclopedic museums need to do a better job of painting the full picture of art history, women and artists of color included. But there is something special about a space fully dedicated to women.

Here, women stand on their own, their cultural contributions celebrated and acknowledged independent of the established canon, without being defined by male achievement. It’s refreshing—and, as strange as it may seem, utterly unique among institutions around the world.

The artists on view are a mix of heavy hitters and welcome discoveries. At the entrance, visitors are greeted by a stunning six-foot-tall red chandelier, crafted from Murano glass and hand-crocheted wool by Joana Vasconcelos. It’s a fitting lead-in to the museum’s ornate Great Hall, with its soaring ceilings and glittering chandeliers. (That’s where you’ll spot the Kahlo.)

Joana Vasconcelos, Rubra (2016). Collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, gift of Christine Suppes, ©Atelier Joana Vasconcelos. Photo by Francesco Allegretto.

The reinstalled collection galleries, set to be on view the next two years and christened “Remix: The Collection,” are arranged thematically, by subject matter, medium, or even color. (The museum purposely eschewed the chronological approach preferred by most institutions, as it tends to leave women and artists of color to the end of one’s visit, with tired feet and tired eyes.)

A five-foot-tall Nikki de Saint Phalle sculpture, Pregnant Nana (1995), stands guard at the entrance, a celebration of motherhood and fertility that perfectly sets the tone for a presentation that addresses women’s traditional domestic roles, work in mediums traditionally relegated to the realm of craft, and feminist empowerment.

Nikki de Saint Phalle’s Pregnant Nana (1995) in the collection galleries at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Photo by Jennifer Hughes, courtesy of NMWA.

One particularly striking work is SoHo Women Artists (1977–78) by May Stevens, an acrylic-on-canvas group portrait of her female neighbors in downtown New York, including critic Lucy Lippard and artists Harmony Hammond, Joyce Kozloff, and Louise Bourgeois.

Created in the tradition of large-scale academic history paintings, the work brought to mind the celebrated 1951 LIFE magazine photo “The Irascibles,” featuring 15 Abstract Expressionist artists, and just one woman (Hedda Sterne) among them.

May Stevens, Soho Women Artists (1978). Courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC/RYAN LEE Gallery, New York, ©May Stevens.

Though Stevens was depicting the women behind the feminist magazine Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, the plethora of talented women on view in the NMWA galleries makes one long for a series of other equally grandiose group portraits lionizing female and non-binary talent from other movements, time periods, and parts of the world.

As many impressive works as the curators have managed to squeeze into the 18,800 square feet of gallery space—you’ll pass by pieces by Clara Peeters, Marisol, Barbara Hepworth, Alma Thomas, Amy Sherald, and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith in relatively quick succession—there’s definitely the sense that the museum is only beginning to scratch the surface of female artistic accomplishment.

Clara Peeters, Still Life of Fish and Cat (after 1620). Collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay

To help the institution usher in its next phase, NMWA tapped Sandra Vicchio and Associates, an architecture firm well-versed in working with historic buildings. (The work was projected to cost $67.5 million, with a final figure of $70 million. So far, $68.7 million has been raised.)

“Transforming a historic building is not easy, but [Sandra] has given us everything we wanted, everything we needed, and more,” museum director Susan Fisher Sterling said at the preview. “Our iconic building has never looked as fresh and inviting as it does today.”

The renovation does include some visible upgrades, including a new “learning commons” with a reference library and educational studios for hosting art classes and activities. But a lot of the changes are more behind the scenes, such as roof repairs, upgraded lighting, and structural improvements that allow for the suspension and display of heavy monumental sculptures—the kind of ambitious work that is the subject of “The Sky’s the Limit,” the reopened museum’s inaugural temporary show.

Installation view of works by Ursula von Rydingsvard in “The Sky’s the Limit” at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Photo by Jennifer Hughes, courtesy of NMWA.

The curators are definitely showing off their new capabilities in the exhibition, which includes both recent acquisitions on view for the first time and loans of work arranged directly direct from artists’ studios, as well as from private collectors.

All 33 of the works date from the last 20 years. These include the world’s longest photograph, an unfurling marvel of over 100 feet by Mariah Robertson that functions more like a sculpture, hanging down from the ceiling and draped across most of one gallery.

Other highlights include a room of Ursula von Rydingsvard’s monumental abstract cedar wood sculptures, and a dramatically installed Alison Saar sculpture, Undone, of a Black female figure seated against the wall but 16 feet up in the air, a transparent white dress hanging down to the floor, its hem dipped in blood-like red.

Alison Saar’s Undone (2012) in “The Sky’s the Limit” at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Photo by Jennifer Hughes, courtesy of NMWA.

Upstairs, there are two smaller solo shows. One features contemporary Chinese American painter and printmaker Hung Liu, who died in 2021. She based much of her work on historic photographs of pre-revolutionary China, elevating their typically anonymous subjects with elegant portraits in vibrant colors. The show includes a promised gift to the museum as well as two newly acquired major paintings, Summer With Cynical Fish (2014) and Winter With Cynical Fish (2014). (There are hopes of eventually securing the other two seasons in the series to complete the quartet.)

Yet another gallery presents the full suite of prints in The Entrance of the Emperor Sigismond Into Mantua, the most notable work by Antoinette Bouzonnet-Stella, a 17th-century French engraver who trained under her uncle at his studio and workshop at the Louvre in Paris. It’s the first time the museum has exhibited the works, which reproduce a Renaissance stucco frieze by Giulio Romano and Francesco Primaticcio, in 15 years.

“Hung Liu: Making History” at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Photo by Jennifer Hughes, courtesy of NMWA.

Altogether, the reopened museum presents a wide range of work by women and nonbinary artists that does more than just expand the art historical canon. It breaks it open, making clear what a limited story is told by the traditional text books and museums. Now, thanks to its revamped and renovated facilities, NMWA is prepared to write that story’s next chapter.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts reopens October 21, 2023, at 1250 New York Avenue, NW, Washington, D.C. “Remix: The Collection” is on view October 21, 2023–October 21, 2025. “The Sky’s the Limit” is on view October 21, 2023–February 25, 2024. “Impressive: Antoinette Bouzonnet-Stella” and “Hung Liu: Making History” are on view October 21, 2023–October 20, 2024.