People

The Art World Remembers the Late Painter Hung Liu, Who Valorized Everyday Immigrants in Monumental Portraits

The artist was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer last month.

The artist was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer last month.

Sarah Cascone

On the eve of her first museum retrospective, Oakland-based painter Hung Liu, one of the first Chinese artists to find success in the U.S., died on Saturday, August 7 from pancreatic cancer. She was 73.

Over the course of her career, Hung Liu created large-scale paintings and installations based on photographs, often drawn from her own family history as well as those of other immigrants and refugees.

“She left this world in the same way she lived, with compassion for those who will miss her so profoundly, with immense courage, and with unthinkable generosity and grace,” the artist’s Santa Fe gallery, Turner Carroll, wrote on its website.

“Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands” is due to open at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., on August 27. It will be the institution’s first solo show by an Asian woman.

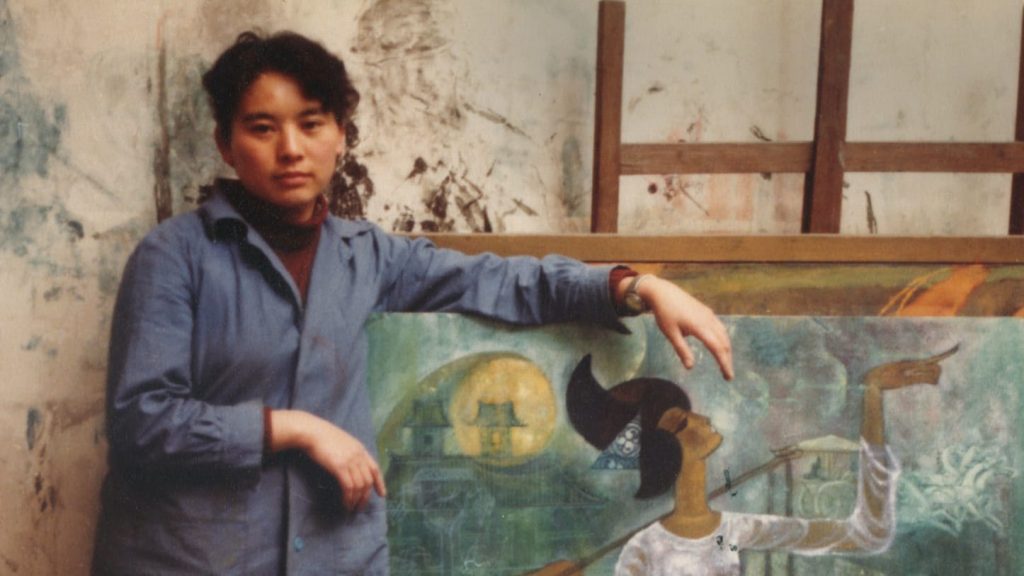

Hung Liu. Photo courtesy of Hung Liu and Jeff Kelley.

“The National Portrait Gallery mourns the loss of Hung Liu, whose extraordinary vision reminds us that even in the midst of despair, and when people help each other, there is joy,” Kim Sajet, the museum’s director, said in a statement. “She believed in the power of art—and portraiture—to change the world.”

Born in Changchun, China, in 1948, just months before Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China, Hung was a baby when her family fled the Red Army. Her father was imprisoned, and she did not see him again until 1994. During the Cultural Revolution, the artist herself spent four years doing manual labor in the countryside for “re-education.”

Hung Liu in 1972. The art spent four years doing manual labor during China’s Cultural Revolution. Photo courtesy of Hung Liu.

Out of fear of the government, Hung burned most of her family photographs during the Cultural Revolution. “Even to have a family photo taken, that itself showed that you were not poor enough,” she explained to the Smithsonian’s Portraits podcast just last month. “In China, the poor are the most trustworthy.”

This loss led to a fascination with old photographs that became the foundation of much of Hung’s work, creating work that she hoped gave voice to the working class, to people lost to memory. Her canvases are overlaid with linseed oil that causes the paint to drip, a style she dubbed “weeping realism.”

These layered visions of the past speak to the difficulties of life in Maoist China. Hung also documented the challenges of the immigrant experience. She spent her last few years making works based on Dorothea Lange’s photographs from the Oakland Museum of California’s archive, seeing parallels between families displaced by the Dust Bowl and the Chinese farmers of her youth.

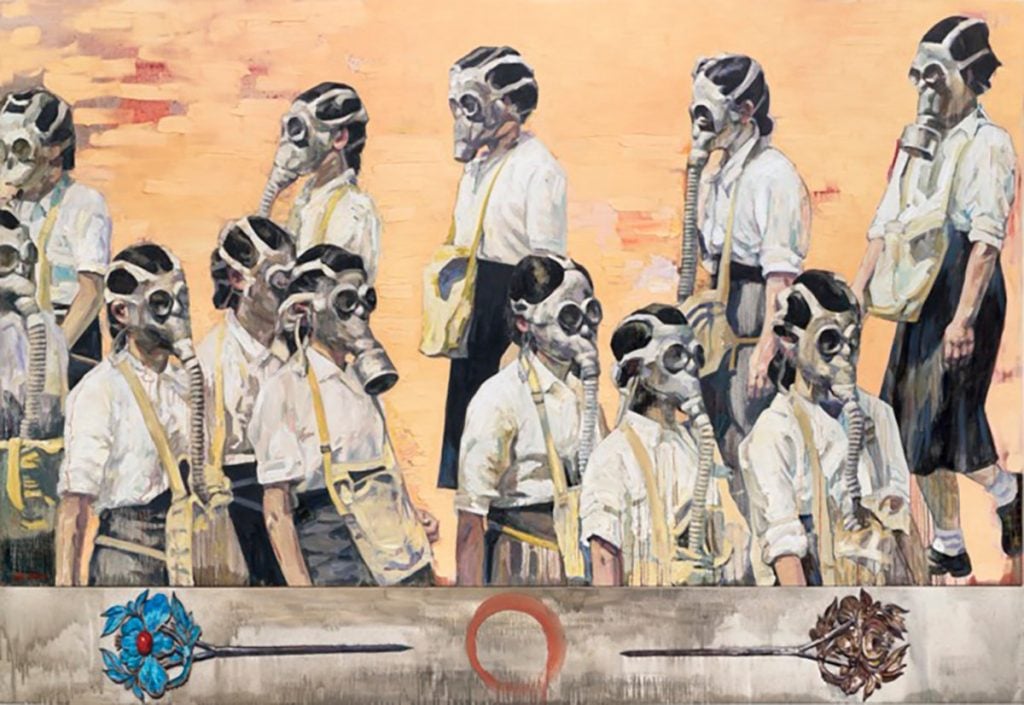

Hung Liu, Twelve Hairpins of Jinling (2011). The painting was based on a photograph from World War II. ©Hung Liu.

“Whether exploring the conditions of women and children, the brutality of the Cultural Revolution, or the collapse of American feudalism, Liu’s paintings humanize the lives of everyday people,” artist Carrie Mae Weems told Turner Carroll. “She’s remarkable.”

In recent years, Hung’s work had become controversial in China, where a 2019 exhibition at the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing was canceled due to government censorship.

The artist initially trained in Social Realism, the propagandistic style favored by the Communist regime, at Beijing Teachers College and the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing. After waiting four years for a passport, Hung moved to the U.S. in 1984 to study at the University of California San Diego under Allan Kaprow, Fluxus artist and Happenings pioneer.

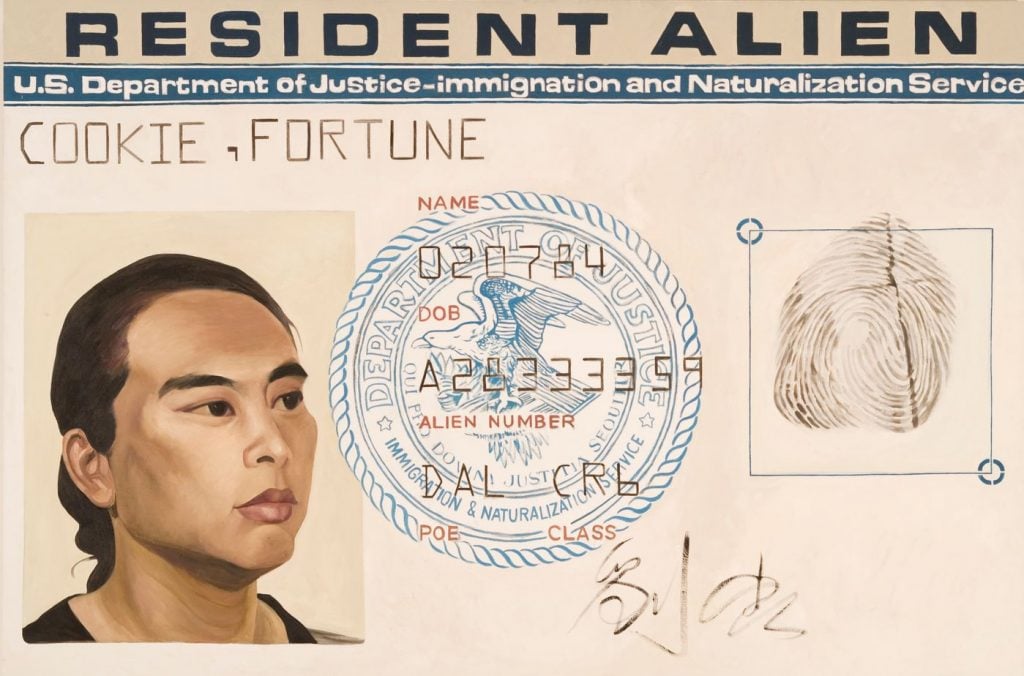

Hung Liu, Resident Alien (1988). Collection of the San Jose Museum of Art, gift of the Lipman Family Foundation, ©Hung Liu.

It was at a 1988 residency San Francisco’s Capp Street Project that Hung painted one of her best-known canvases, Resident Alien, a self-portrait of the artist’s green card replacing her birthdate with her date of arrival in the U.S. and her name with “Cookie, Fortune.”

Other major works include Going Away, Coming Home, a 2006 layered glass mural permanently installed at the Oakland airport that measures 10 feet by 160 feet. Currently, she has a solo show at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, featuring Resident Alien.

Hung’s work appears in the collection institutions including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art and Metropolitan Museum in New York City, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Hung Liu, Going Away, Coming Home (2006) at the Oakland International Airport. ©Hung Liu.

“Hung Liu was such a vibrant and vital part of the art world in the Bay Area and beyond,” de Young curator Janna Keegan said in a statement. “Hung Liu’s art practice focused on recovering the stories of people who have been often forgotten in traditional historical narratives. The legacy and wonderful oeuvre she leaves behind will ensure that she too will always be remembered.”

Hung is survived by her husband, art critic Jeff Kelley, their son, Ling Chen Kelley. She is also represented by Rena Bransten Gallery in San Francisco.

See more photos of the artist and her work below.

Hung Liu in her studio with Rat Year (2020). Photo by John Janca, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. ©Hung Liu.

Hung Liu, Sisters (2000). Collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., gift of the Harry and Lea Gudelsky Foundation, Inc.; ©Hung Liu.

Hung Liu at the opening of “Hung Liu: Golden Gate (金門)” July 14, 2021, at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Photo by Drew Altizer, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Hung Liu, Untitled (2005, from “Seven Poses” series. Collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, gift of the Greater Kansas City Area Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. ©Hung Liu.

Hung Liu. Photo by Paul Andrews, courtesy of the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art.

Hung Liu, Winter Blossom (2011). Collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Steven Scott, Baltimore, in honor of the artist and the Twenty-fifth Anniversary of the National Museum of Women in the Arts; ©Hung Liu.

Hung Liu, Migrant Mother: Mealtime (2016), based on a Depression-era photograph by Dorothea Lange. Collection of Michael Klein, ©Hung Liu.

“Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands” will be on view at the National Portrait Gallery, 8th and G Streets NW, Washington, D.C., August 27, 2021–May 30, 2022.

“Hung Liu: Golden Gate (金門)” is on view at the de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco, California, July 17, 2021–March 13, 2022.

“Hung Liu: Sanctuary” will be on view at Turner Carroll Gallery, 725 Canyon Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico, August 20–September 19, 2021.

“Hung Liu at Pie Projects” will be on view at Pie Projects, 924B Shoofly Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico, August 21–September 11, 2021.