Art World

As the Restitution Debate Rages on in Europe, Could the Solution Lie in the Art of the High-Tech Copy?

Technologies like VR and 3D modeling could have a role to play in the conversation about the restitution of colonial-era objects.

Technologies like VR and 3D modeling could have a role to play in the conversation about the restitution of colonial-era objects.

Kate Brown &

Naomi Rea

In 2015, a duo of artists unveiled a 3D-printed copy of the bust of Queen Nefertiti—the more than 300-year-old limestone sculpture that attracts thousands of visitors each year—in Egypt, its country of origin. They called the act “digital repatriation.” The original artifact—which had been uncovered and taken from Egypt by a German archaeological team 100 years earlier—remains on view in the Neues Museum in Berlin to this day, despite the Egyptian government’s repeated requests for its return.

At the time, the artists’ move was hailed as “the world’s most ethical art heist” because they claimed to have surreptitiously scanned the work in the museum with a mobile device. Their exploits paved the way for an important conversation about the role technology might play in the ongoing debate around restitution, as well as museums’ reluctance to allow unrestricted access to their collections.

In the years since Nora al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles’s self-described Nefertiti “hack,” the conversation surrounding the return of objects with troubling provenance, particularly those acquired during the colonial era, has reached new heights.

Could technology help this process along? Would it be possible to create faithful reproductions of objects that Western institutions could house in lieu of the originals? Or might these replicas serve as a helpful tool in the development of a sharing arrangement?

Some artists, tech companies, and a few institutions believe technology has a valuable role to play in restitution. But this conversation is only possible because of the rapid acceleration of augmented and virtual reality, 3D printing, and other technologies, some of which are already in use in museums.

VR experiences now allow people to make virtual visits to fragile Egyptian tombs and take in extremely sensitive cave paintings at full scale. In Boston, a tech start up used the magic of augmented reality to return masterpieces stolen in the infamous 1990 heist to their frames at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

One of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum paintings stolen in 1990, Rembrandt van Rijn’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, returned to its frame through the magic of augmented reality. Photo courtesy of the Cuseum.

Elsewhere, advances in 3D scanning and printing offer up possibilities for creating faithful replicas. In 2016, conservation experts brought a precise recreation of the archway from Palmyra’s 2,000-year-old Temple of BeI to New York and London to raise awareness about the destruction of the ancient Syrian city. Meanwhile, some of the Parthenon marbles from the British Museum were 3D scanned in high resolution by an architecture firm in 2012 and duplicated in concrete for the London Olympics athletes’ village residences.

Many museums also already show or retain objects that are not original. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London, for example, has two large halls dedicated to copies, from Michelangelo’s David to Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise. These casts may not carry the same monetary value or history as the originals, but they can be considered just as beautiful and still provide considerable educational value.

“It is currently incredibly easy to create accurate 3D copies of many types of historical artifacts, but you don’t hear of 3D replicas forming the cornerstone of many restitution agreements—yet,” says Thomas Flynn, who specializes in cultural heritage at the 3D modeling company Sketchfab, which houses official 3D scans of some of the British Museum’s most contentious objects, including a monumental Moai from the island of Rapa Nui called Hoa Hakananai’a and the Rosetta Stone.

Soon, stakeholders may have no choice but to start discussing the role technology might play in restitution. Repatriation claims are growing by the day. The issue has become even more urgent as museums race to digitize their collections, and more and more source countries become aware of the location of their stolen treasures.

Meanwhile, the political landscape is changing. This year, officials at the highest levels of international government—most visibly, French President Emmanuel Macron—began to seriously entertain the idea of, and even advocate for, restitution of colonial-era objects.

This November, a radical report commissioned by the French government advised the country to embark on a progressive and permanent restitution campaign to return every object it unjustly acquired during the colonial period. The authors touched on the potential role of high-tech replicas to fill the void in European collections.

“It is even possible to consider the creation of apparatuses to fill the void left by these objects, in the guise of the creation of replicas to be housed in Western museums, whose energetic aura will be assured through the machinery of narrative and the possibilities that digital tools allow for as well as ICT (Internet Communications Technology),” the report stated.

The authors mention how the keepers of the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave, home to fantastic prehistoric cave drawings that have been sealed off from the public for more than 20 years, have similarly suggested creating a facsimile for visitors “to continue to appreciate cultural history while also preserving the original and simultaneously losing none of the experiential and emotional effects of a visit to such a site.”

Meanwhile, Indigenous artists in Canada are currently creating convincing replicas of objects to provide museums in lieu of the originals, while an artisan from Rapa Nui has offered to make a copy of Hoa Hakananai’a to replace the original sculpture the island is trying to reclaim from the British Museum.

At the same time, sympathetic academics are proposing a shift in the way institutions think about the value of objects. Maxwell Anderson, the president of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and a former director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, wrote in a recent op-ed for The Art Newspaper that it is “essential” to harness this technological wizardry in replication to mediate moral contests.

And a conference at the Vatican in October, the Italian Egyptologist Christian Greco said before a room of museum professionals, “We must not insist on the sacrality of the original.”

But as Nefertiti hackers Nora al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles pointed out with their work, which was based on a scan they had to capture in secret, not all museums are as eager to provide unfettered access to their collections.

“They had the data many years before and never made it accessible to the public,” the artists told artnet News by email of the Neues Museum’s scan, adding that Germany is among many European countries that adopt a conservative and proprietary view of their collections. (It should be noted that after news of their stunt broke, some experts claimed the artists’ facsimile must have been created from a hacked version of the museum’s own scan, rather than via mobile device, as they claimed.)

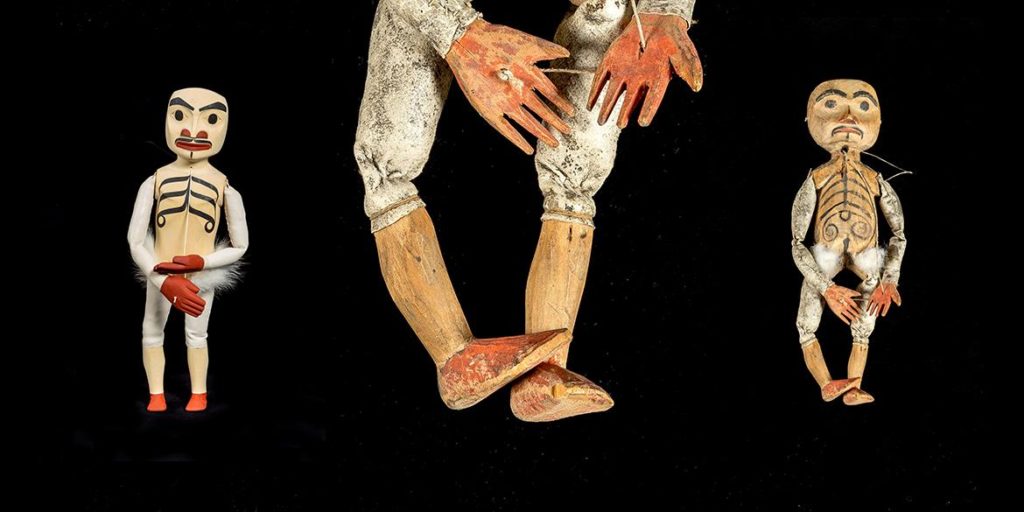

From left: David Robert Boxley, Tsimshian (2014) and a detail and full view of a Tsimshian string puppet by an unknown artist that belongs to the Burke Museum in Seattle. Photos by Richard Brown Photography.

Advocates say that opening up museum collections for research purposes is an important step in decolonizing knowledge, an element that tends to get swept aside in the rush to claim ownership of physical objects. Scholars and artists from source countries, they say, must have free access to their own histories, even as the ultimate ownership over artifacts is still being hashed out.

With this tenet in mind, the Burke Museum in Seattle, which has a large collection of Indigenous art, has invited around 150 artists and scholars over the past decade to study their collections close up. While some end up creating replicas, most contemporary artists use the objects as inspiration to create their own work, or as a tool for teaching. “The objects in the Burke’s collection are imbued with the knowledge of their makers and can be a catalyst for transferring this knowledge across generations of artists,” says Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, the Burke’s curator of Northwest Native art.

Thierry Oussou performed and documented a fake archeological dig for Impossible Is Nothing (2016). Photo: Thierry Oussou. Courtesy Tiwani Contemporary.

A work included in this year’s Berlin Biennale illustrates the point well. The artist Thierry Oussou’s installation Impossible Is Nothing reproduces a 2016 archaeological dig in Benin through video documentation of the excavation alongside copies of the real objects researchers found, from axe blades to a royal throne.

The project illustrates both the possibilities and limits of technical reproduction, which can serve as a valuable educational tool but ultimately cannot make up for the pride museums—and indeed, nations—take in presenting the real thing. Today, “Africa is empty of its riches,” the artist told the Guardian. “When young students wish to write about the treasures of their homeland, they have to travel to France to do their research. But when I was in Benin, I didn’t have the money to buy a plane ticket like that.”