On View

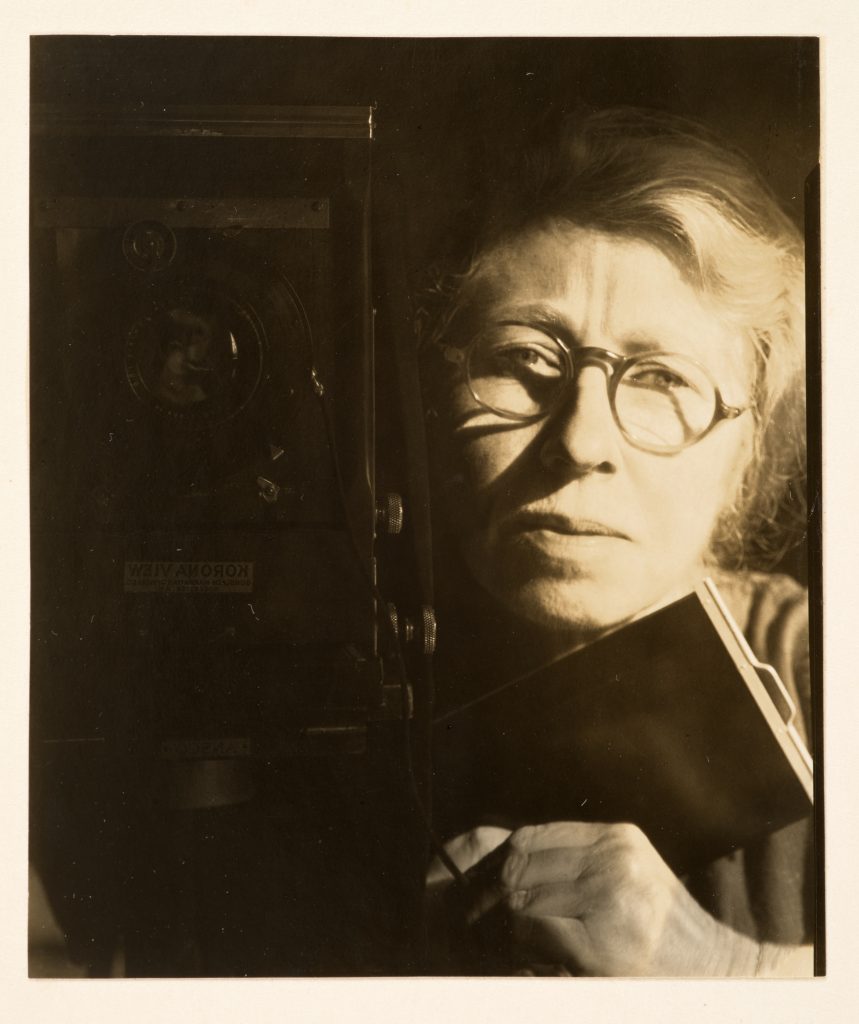

A New Retrospective Reveals Photographer Imogen Cunningham’s Masterful Range—and How It Hurt Her Career

On view now at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the show spans six decades of the artist's career.

On view now at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the show spans six decades of the artist's career.

Taylor Dafoe

Sometime late in Imogen Cunningham’s life, a younger female photographer asked her, “What do I have to do to become more famous, to have my work appreciated?”

“You have to live longer,” Cunningham replied. (The artist receiving the advice? Ruth Bernhard.)

A joke, surely, about the art world’s tendency to appreciate the artistic contributions of women only after they’ve entered the last chapter of their lives, the retort nevertheless contained some plain truth for Cunningham. It wasn’t until 1960, when she was in her late 70s, that she experienced the first real financial success of her then decades-long career—one of the most influential in the history of photography.

To call Cunningham underrated or overlooked might be inaccurate; despite the meager money she made, she’s rightly considered among the 20th-century greats. Still, her name doesn’t ring as familiar as that of, say, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, or Dorothea Lange.

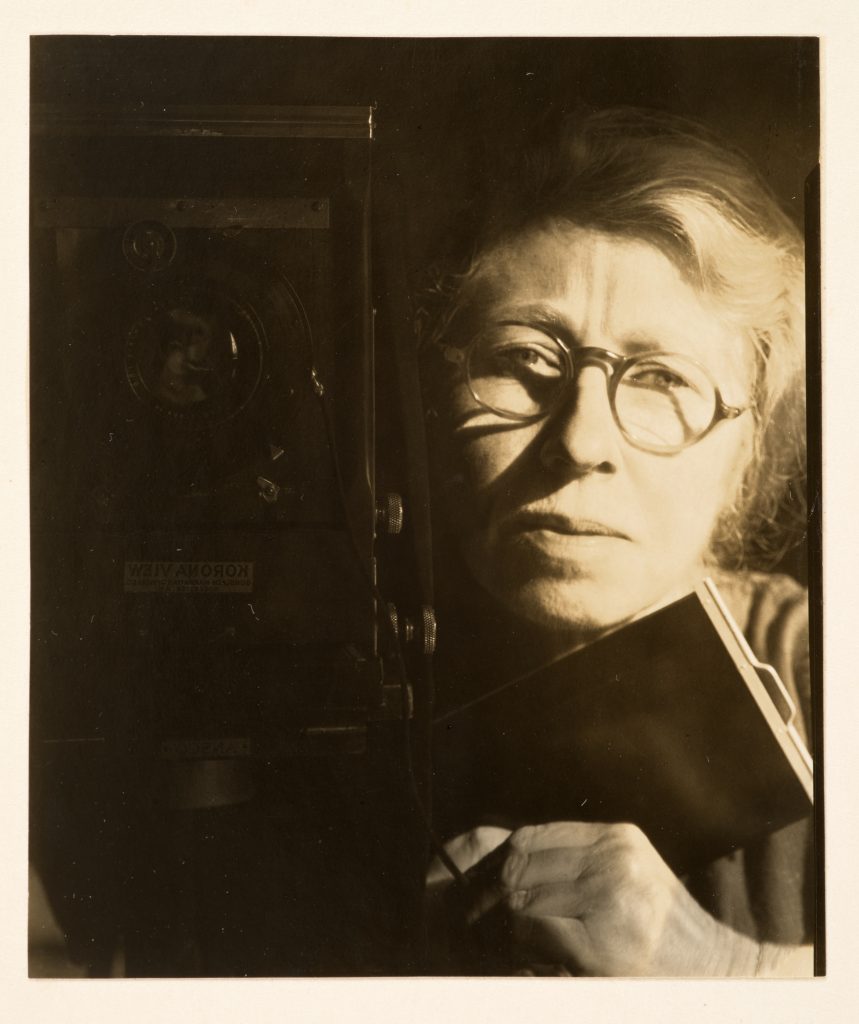

Imogen Cunningham, The Unmade Bed (1957). © Imogen Cunningham Trust.

There’s a reason for that, said Paul Martineau, a curator at the J. Paul Getty Museum, who has just organized a major retrospective of Cunningham’s work.

The name of each of those photographers—all friends of Cunningham’s—comes with a specific image. For Adams, it’s the Western mountainscape; for Weston, the fleshly pepper. Cunningham, on the other hand, “didn’t make one type of picture,” said Martineau. It’s the paradox at the heart of her legacy: the quality that separates her art is the reason people underappreciate it.

“You can’t really assign a label to Imogen,” he went on, calling Cunningham a “pioneer in the field for women.”

“She wasn’t satisfied with anything… She wasn’t rehashing things over and over again like some artists. She was always pushing herself to innovate, to learn more and experiment.”

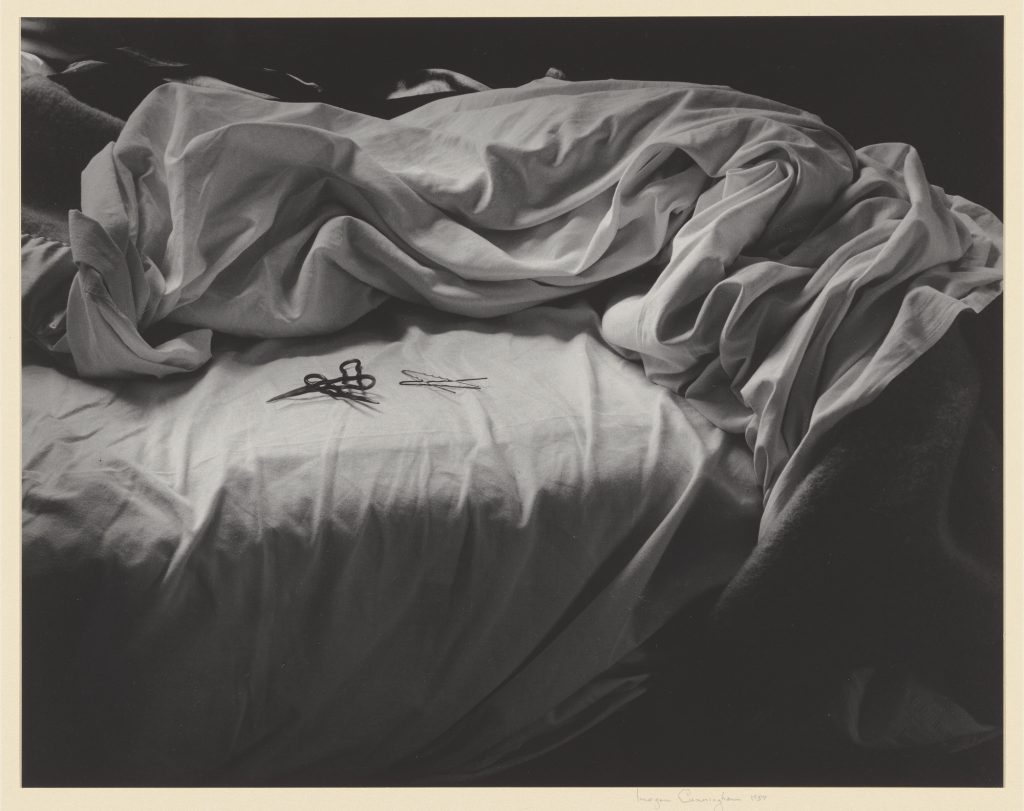

Imogen Cunningham, Amaryllis (1933). © Imogen Cunningham Trust.

Cunningham’s capacity for reinvention is on full display in the Getty retrospective, which spans six decades and 180-some prints (roughly three dozen of which were made by contemporaries like Judy Dater, Lisette Model, and Alfred Stieglitz).

Included are her early pictorialist experiments, made in her late 20s and 30s while living in Seattle with then-husband Roi Partridge; her carefully studied botanical photographs she made upon moving to the Bay Area in 1917; the richly detailed pictures she produced while working alongside Sonya Noskowiak, Paul Strand, and the other artists with whom she co-founded Group f/64; and many other bodies of work.

And yet, if the exhibition instantiates the stylistic range of Cunningham’s pictures, then it also highlights the subtle artistic tendencies that tie the works together. These are most apparent when looking at Cunningham’s work in portraiture, a constant throughout her career.

Making pictures of her children or editorial portraits of celebrities for Vanity Fair, Cunningham preferred an intimate approach bereft of artificiality. Rarely did she manipulate her images in the darkroom or even let her sitters wear makeup.

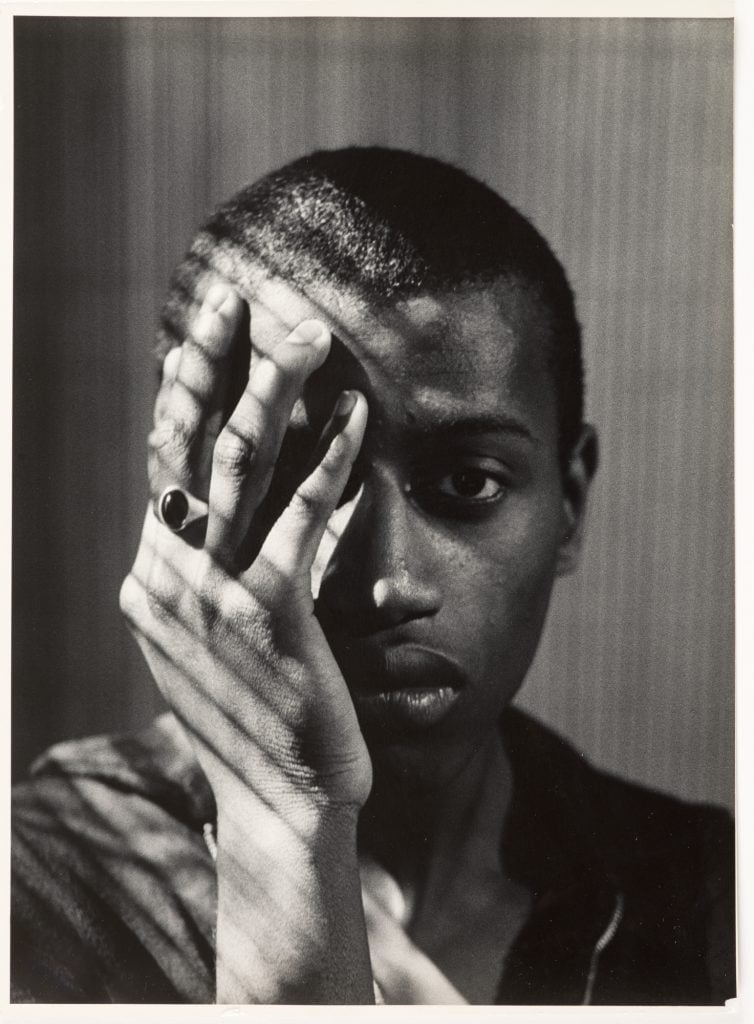

Imogen Cunningham, Stan, San Francisco (1959). © Imogen Cunningham Trust.

“Cunningham didn’t like to indulge people’s vanity,” Martineau explained. “She’s trying to find the real likeness rather than making people beautiful.”

She also had a special penchant for capturing other creatives on film, such as dancer Martha Graham, painter Frida Kahlo, writer Gertrude Stein, and fellow photographer Minor White. Her pictures of Ruth Asawa, one of her closest friends, are some of the most sensitively realized portraits of an artist you’ll ever see.

In the early 1930s, she was sent to Hollywood to photograph “ugly men” like Cary Grant, Spencer Tracy, and Wallace Beery. Cunningham recalled the assignment on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in 1976, the last year of her life.

“Did you consider [Grant] an ugly man?” Carson asked the aging photographer in the segment.

“He convinced me that he wasn’t,” she said knowingly. The crowd erupted in laughter.

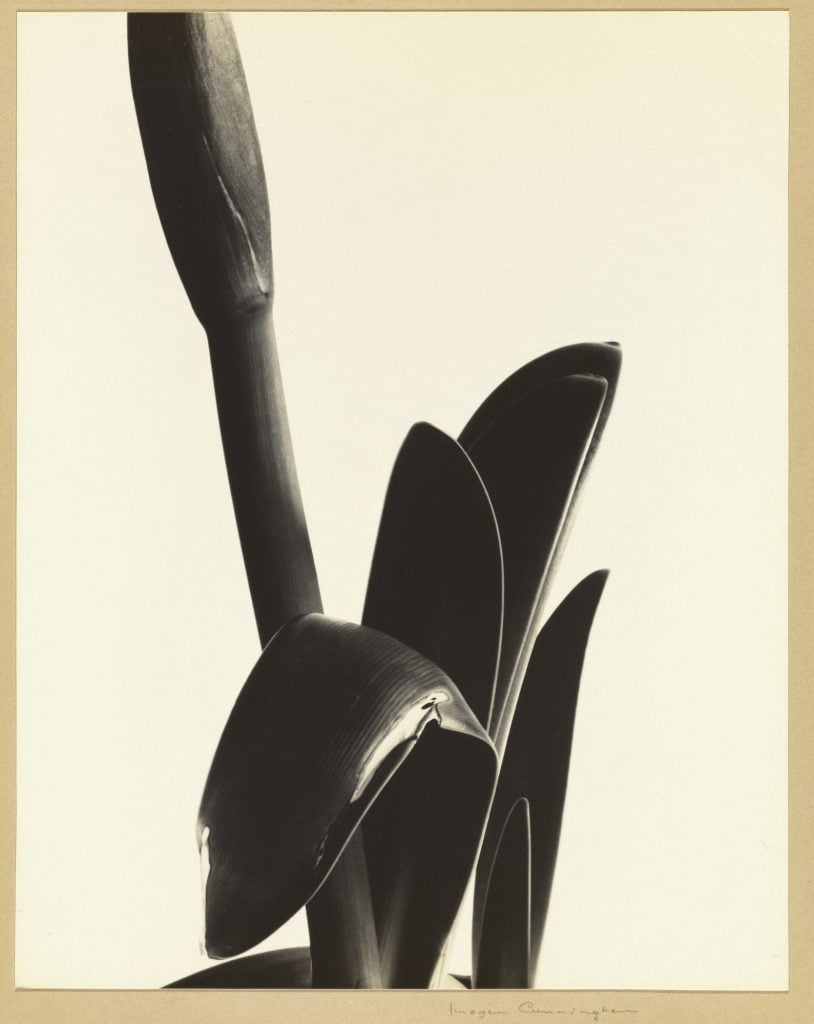

Imogen Cunningham, Self-Portrait with Elgin Marbles, London (1909-10). © Imogen Cunningham Trust.

But for Martineau, Cunningham’s signature portrait wasn’t of an artist or actor. It was of herself—and it came just a few years into her career. The self-portrait, made around 1909, shows the young artist before a small plaster cast of the Elgin Marbles, a sketchbook and pencil in hand.

“She’s basically putting herself in the trajectory of the history of art, reaching back to the ancient Greeks,” the curator said. “It sets the tone for the rest of her career. She considered herself an artist and she wanted to leave something behind for generations to come, something of value.”

Indeed, the world may have needed 50 years to recognize her talent, but Cunningham saw it in herself right away.

“Imogen Cunningham: A Retrospective” is on view now through June 12 at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.