Artnet Auctions

‘Watercolor Sits on the Edge of Control and Abandon’: How Artist Richard Dupont Rediscovered Drawing With His ‘Islands’ Series

On the occasion of his Buy Now sale, we spoke with artist Richard Dupont.

On the occasion of his Buy Now sale, we spoke with artist Richard Dupont.

Samantha Baldwin

When the pandemic began, New York-based artist Richard Dupont found himself far from his studio, with only ink and watercolor paper.

For the artist, who is widely recognized for works that bridge the digital and physical worlds, drawing was always a space for experimentation and spontaneity, and his recent series “Islands” was the next step in his extensive exploration of chance operations.

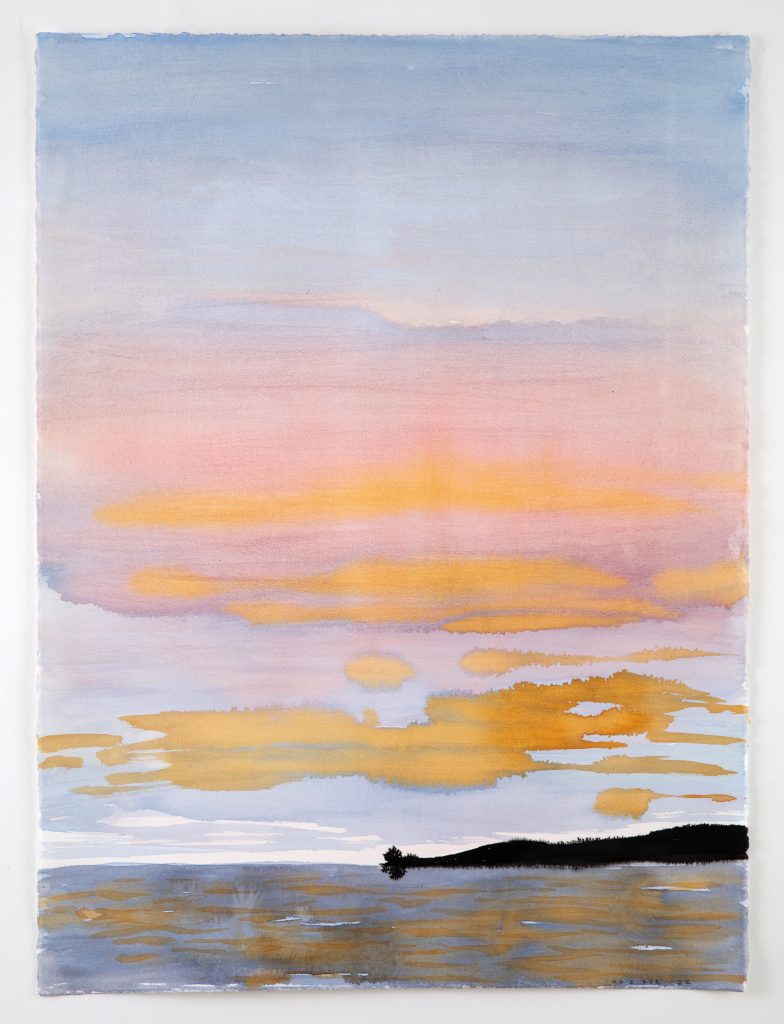

Begun in Maine during the summer of 2020, these landscapes convey an emotional state, and act as a meditation on the isolation of our online experiences.

On the occasion of Buy Now: Islands by Richard Dupont, live for immediate purchase on Artnet’s Buy Now platform, we had the opportunity to speak to Dupont about his early figurative works, performance art, and the very particular emotional impact of a sunset over water.

Be sure to explore Buy Now: Islands by Richard Dupont, and purchase your own “Island” before June 14.

Richard Dupont, Islands 203, 2022. Available now in Buy Now: Islands by Richard Dupont.

Throughout your career, you have used technology as a means to explore the human form. What is it about the human figure that inspires you?

Initially I came at it not in the conventional sense of being interested in portraiture or figuration. I was much more influenced by the history of body art and performance art, and the idea of the artist using their own body as the site of their work or as raw material. Artists like Ana Mendieta, Bruce Nauman, and Chris burden were really interesting to me.

I was of the first video game generation, so straight performance art was never as appealing. Early on, I came up with an idea of making a virtual version of myself—like a character version—and using that as the performer. In the early 2000s, it was almost impossible to find any kind of 3D printer or body scanner. But within a couple of years there was an explosion in technology. So I found a video game company on Long Island that had a body scanner. I was able to rent that scanner, and I made a scan of my head. I then started manipulating that head on the computer and distorting it. That was really the beginning of things.

After that, I thought, “I have to do my body.” At the time, there were two places you could go: California, where the movie industry was exploring CGI effects, or the military industrial complex, which was using body scanners to design things that interface with the bodies of military personnel.

I ended up going to the military base because I was interested in how the technology of body scanning and tracking people was being co-opted by the military industrial complex. Back then it was the very beginning of that creeping sensation that privacy was starting to be eroded and technology was infiltrating our lives in a way that I could see becoming detrimental.

Your interest in performance art shines through in your work and your installations. The life-sized figures make viewers feel like a part of the performance. Is that something you think about when you’re putting together an installation?

Absolutely. I always thought of them as surrogate performers. And I’m also interested in that line where static sculpture can cross over and be more performative. It’s not just the arrangement of them in a public space, but also the fact that there are distortions that can only be experienced by the viewer walking through and around it. It becomes a physiological thing. I’m really interested in sculpture affecting space. I have an interest in Charles Ray and Richard Serra, both sculptors who really think about space.

Richard Dupont, Islands 194, 2022. Available now in Buy Now: Islands by Richard Dupont.

The “Islands” series featured in Buy Now is very distinct from your previous works. How does the sporadic nature of watercolor differ from your more calculated and technical sculptural works?

I love the idea that if you follow a process in art making, it can lead to things that are surprising, and accidents can be allowed to happen. Following a plan over a long period of time can be tiresome. It’s sometimes hard to remain flexible and intuitive with sculpture. Drawing, for me, has always been a way to work in the moment. Anything can be allowed to happen.

In the summer of 2020, when we were quarantining in Maine, I had hardly any supplies with me. But I brought some paper and some ink, and I just started working. And I kept going. I thought, “This is sort of satisfying.” Initially, it was a very basic motif of the landscape and the horizon, but the more I did it, the more it was opening up, and I started working on different kinds of paper and getting effects that I liked. I was looking at Chinese ink painting, and then Emil Nolde, Winslow Homer, and Anselm Kiefer. Much of my previous work has been concerned with finding a space for the hand within mechanical processes, but these works are all about the hand. The medium of watercolor sits right on the edge of control and abandon.

Richard Dupont, Islands 202, 2022. Available now in Buy Now: Islands by Richard Dupont.

Were these landscapes created from photographs of scenes you saw in Maine, in plein air, or from memory?

They’re mostly done from memory, and it’s a much more internal landscape, rather than an external landscape. I think that’s a result of what I was going through emotionally during the pandemic—this idea of withdrawal.

I didn’t really think about it until later when somebody said, you’re obviously titling these “Islands” because we’re all islands now. We’re all isolated, you know? And I never thought of it, before, but I do feel as though that’s relevant.

What role does color play in these watercolor paintings?

Color is so powerful emotionally. It’s a pipeline into people’s emotions, and perhaps the most direct one in art. It can sort of short circuit the more cerebral response, which is interesting.

The sunset over water is something that strongly resonates with people. These paintings elicit something emotional when you look at them.

What I am trying to do with these is create an emotional connection. It has a lot to do with memory, as they are largely remembered or imagined places. A landscape is not just a landscape, But with the sunsets, there’s an aspect of kitsch, and a sublime element, too. The two exist very closely.