People

Richard Nonas, Whose Hand-Wrought Sculptures Helped Define Post-Minimalism, Has Died at 85

Trained as an anthropologist, Nonas became a sculptor without even realizing it.

Trained as an anthropologist, Nonas became a sculptor without even realizing it.

Sarah Cascone

Anthropologist turned Post-Minimalist sculptor Richard Nonas died in New York on May 11.

Nonas, age 85, died unexpectedly but peacefully in his sleep, according to his New York gallery, Fergus McCaffrey. The artist’s passing was first reported by ARTnews and Artforum.

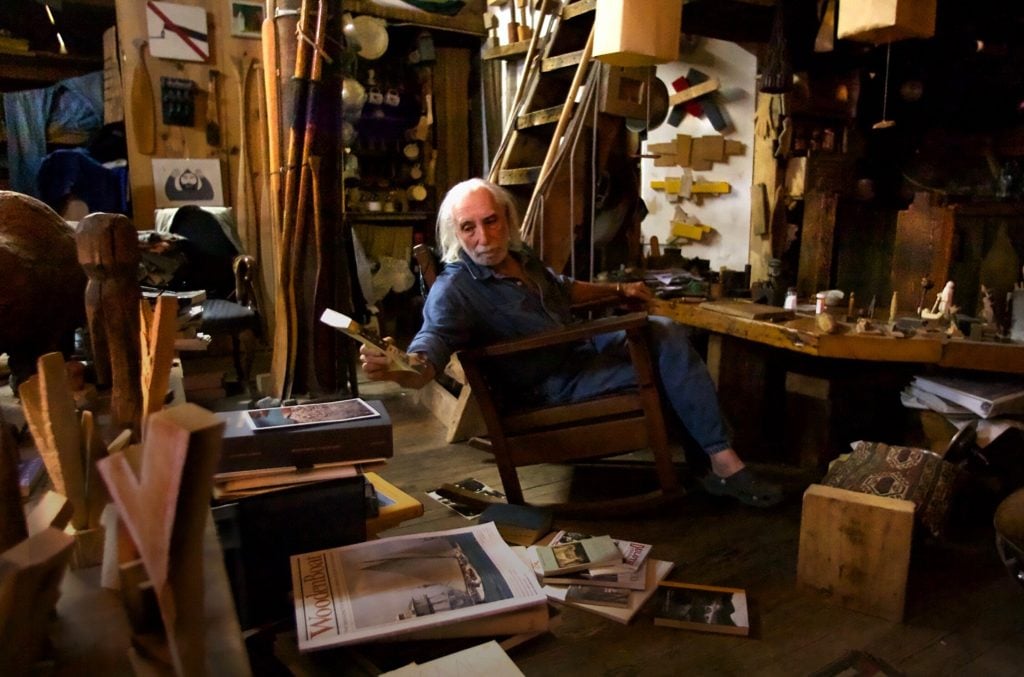

A New York native, Nonas was born in 1936 and studied literature and social anthropology in college. He then worked as an anthropologist, conducting field work about Native Americans for a decade. His travels across North America brought him to Mexico, Canada, and the American Southwest, but it wasn’t until his return to New York in the mid-1960s that he began making art—almost by accident.

While working as an anthropology professor at Queens College, Nonas began picking up pieces of wood he found while out walking his dog.

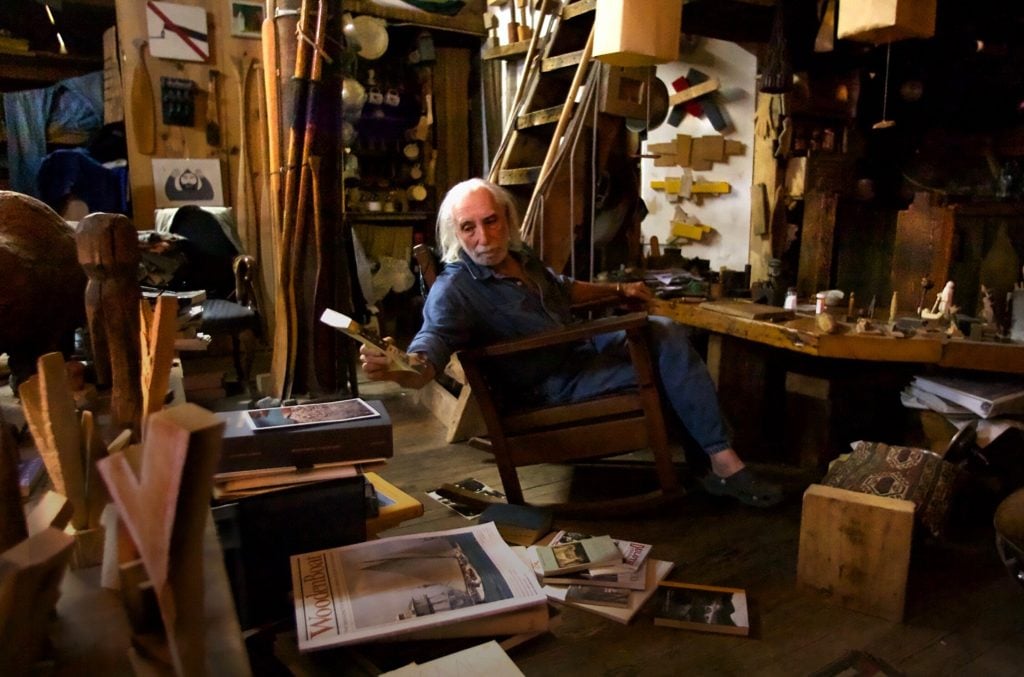

Installation view of “Richard Nonas all; at once,” the artist’s most recent show at Fergus McCaffrey, in 2019. Photo courtesy of Fergus McCaffrey, New York.

“I started taking the wood home and moving it around. The idea of art never occurred to me,” Nonas told the Brooklyn Rail in 2013. “A couple of months later, a friend came to my apartment and said, ‘Idiot, that’s called art. That’s called sculpture.’”

Before too long, Nonas became part of a community of young artists in New York—legend has it that during his first visit to famed art bar Max’s Kansas City, Nonas met Richard Serra and Carl Andre and immediately visited their studios.

It was a transformative time for the city’s art scene, with the emergence of Soho and rise of alternative art spaces such as the artist-run gallery 112 Greene Street, where Nonas showed alongside the likes of Serra, gallery co-founder Gordon Matta-Clark, and performance artist Vito Acconci.

Nonas’s work was also included in “Under the Brooklyn Bridge,” the 1971 exhibition curated by Matta-Clark and Alanna Heiss, founder of PS1 in Queens. The show brought avant-garde assemblages and performances by the likes of Sol LeWitt, Keith Sonnier, and Dennis Oppenheim to the foot of the titular bridge.

For Nonas, sculpture was a deeply emotional and philosophical pursuit. “It’s the way the piece feels that counts—the way it changes that chunk of space you’re both in, thickens it and makes it vibrate—like nouns slipping into verbs,” he wrote in a 1985 notebook.

Using wood, stone, and industrial materials, Nonas aimed to interrupt the surrounding environment with his work, which featured repeated geometric forms.

Richard Nonas, Hip and Spine (Stone Chair Setting) (1997), at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Photo courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Arts.

“As an artist (and friend) Richard Nonas’s cheerful, erudite, contrarian vision, makes pat definitions of his work a challenge. He wouldn’t have it any other way,” Allyson Spellacy, a partner at Fergus McCaffrey, told Artnet News in an email. “To walk through a room or field that the sculptor had, in his vernacular, ‘skewed’ was to experience a charge that could not be mapped by mere language. The evidence of Nonas’s uninterrupted investigations—objects, installations, drawings, books, scrawled notes—will continue to inspire and sustain us. ”

“I distrust sculpture that emphasizes process, duration, or growth. I trust sculpture whose making, and being, is finished immediately…,” Nonas wrote in Bomb in 1989. “I trust sculpture that does not grow, but simply appears—shuddering, like a knife stabbed into wood.”

Institutions that have collected Nonas’s work include Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Whitney Museum of American Art. The artist also has permanent installations at the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Cranbrook Art Museum in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.