Law & Politics

How an Eight-Year Copyright Suit Against Richard Prince Finally Came to an End

The artist will pay two photographers $650,000, an outcome that both sides are spinning in the press.

The artist will pay two photographers $650,000, an outcome that both sides are spinning in the press.

Eileen Kinsella

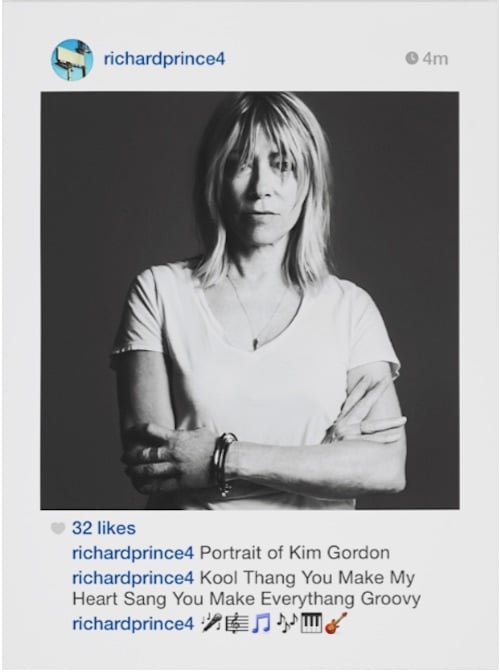

It was almost eight years ago that Eric McNatt, a New York-based commercial photographer, sued artist Richard Prince after Prince used his copyrighted portrait of rock star Kim Gordon in his own Instagram posts, on an enlarged canvas for a gallery show, and in a related book.

McNatt filed in November 2016, alleging copyright infringement and seeking a declaration that the use of the image in the book did not qualify as fair use, a key test of copyright law. He also named Blum & Poe, which exhibited Prince’s piece, as a defendant.

A similar claim was brought by photographer Donald Graham in 2015 against Prince for his use of a photograph titled Rastafarian Smoking a Joint in a work called Portrait of Rastajay92, which Prince exhibited in a 2014 Gagosian show. (Graham also named Gagosian.)

Kim Gordon for Paper Magazine by Eric McNatt. Courtesy of the artist.

After years of legal wrangling, and just days before a jury trial was scheduled to start in federal court in Manhattan, the cases have suddenly come to an end

Judgments filed on January 24 by U.S District Court Judge Sidney H. Stein outline an agreement between the parties that will see Prince pay $650,000 to the photographers without explicitly stating that he infringed their copyrights.

Prince’s decision to settle comes after attempts by him to have the cases dismissed, which were rejected by Stein. Both sides have taken to the press to spin the final result.

Which side can claim victory? The answer, like the case itself, is complicated.

The McNatt court document states, “Judgment is entered in favor of Plaintiff and against Defendants for the claims asserted against them as set forth in the Complaint.” It also outlines some straightforward facts: McNatt registered his Gordon portrait with the U.S. Copyright Office, Richard Prince incorporated it into a work known as Portrait of Kim Gordon, and gallery Blum & Poe released a book including Portrait of Kim Gordon.

Richard Prince’s Instagram post. Image via PACER

The judgment places restrictions on the defendants’ use of both McNatt’s original image and Prince’s take on it, saying that they are “enjoined from reproducing, modifying, preparing derivative works from, displaying, selling, offering to sell, or otherwise distributing” them. (The Graham judgment features similar language.)

McNatt will receive $450,000—”five times the sales price for Portrait of Kim Gordon” when it was exhibited at Blum & Poe—from Prince, and Graham (whose trial was set for later this year) will receive $200,000, with $250,000 more going toward court costs. (The brings the total payments to $900,000.)

Prince’s attorney, Brian Sexton, noted what is not part of the judgments in an email to Artnet News, which he termed “absolute red lines” for the defense: no admission of infringement by Prince, no ruling by Judge Stein of infringement, and no ruling that Prince’s paintings were not protected fair use.

“We absolutely would not settle until any admission of infringement or that Richard’s work was not protected fair use was removed from the settlement consent judgment,” Sexton said. The artist’s studio manager, Matt Gaughan, framed the artist’s decision as a prudent financial move, telling Artnet News by email that Prince “agreed to settle over eight years of costly litigation for a tiny fraction of what trial alone would cost.”

“Anyone tempted to believe the spin that the Court’s judgments are settlements favorable to defendants need look no further than the words of the Court’s orders,” David R. Marriott, an attorney with Cravath Swaine & Moore representing Graham and Nash, said in a statement to Artnet News.

Those hoping for some clarity on the state of fair use in the United States are out of luck. Though the text of the judgment blocks Prince from using the images in various ways, it says nothing about his claim that his art was protected by fair use. That issue would have been decided by a jury, after Judge Stein said at a hearing earlier this month that he could not make that determination.

Marriott termed the resolution a “tremendous victory” for his clients and “for artists’ rights more broadly—particularly because, when it comes to unauthorized takings of other artists’ works, Prince is a repeat offender.”

Marriott added that the cases have been considered a “David vs. Goliath” matter for the art world, and said Graham and McNatt have devoted years of litigation “in the interest of defending their intellectual property rights, advancing copyright law for the benefit of all, and protecting similarly situated artists.”