Art World

Rita Ackermann’s Elusive Quest for Truth (or At Least Cinema Vérité)

In a wide-ranging interview, the artist discusses everything except her compelling dual show "Splits" at Hauser & Wirth in New York.

There’s an intensity to painter Rita Ackermann. Both in her person, crystallized in the sharpness of her bright eyes, and her canvases, which feel fervently worked over, their surfaces betraying traces of marks made then erased. One of her signatures, besides her nymphette angel avatar, a motif increasingly dispersed into abstraction over the years, is a clash of contradictory systems. Her works mix drawing and painting, and are at once figurative and abstract. The Hungarian-born, New York City-based artist’s dual, concurrent exhibitions, open today at Hauser and Wirth.

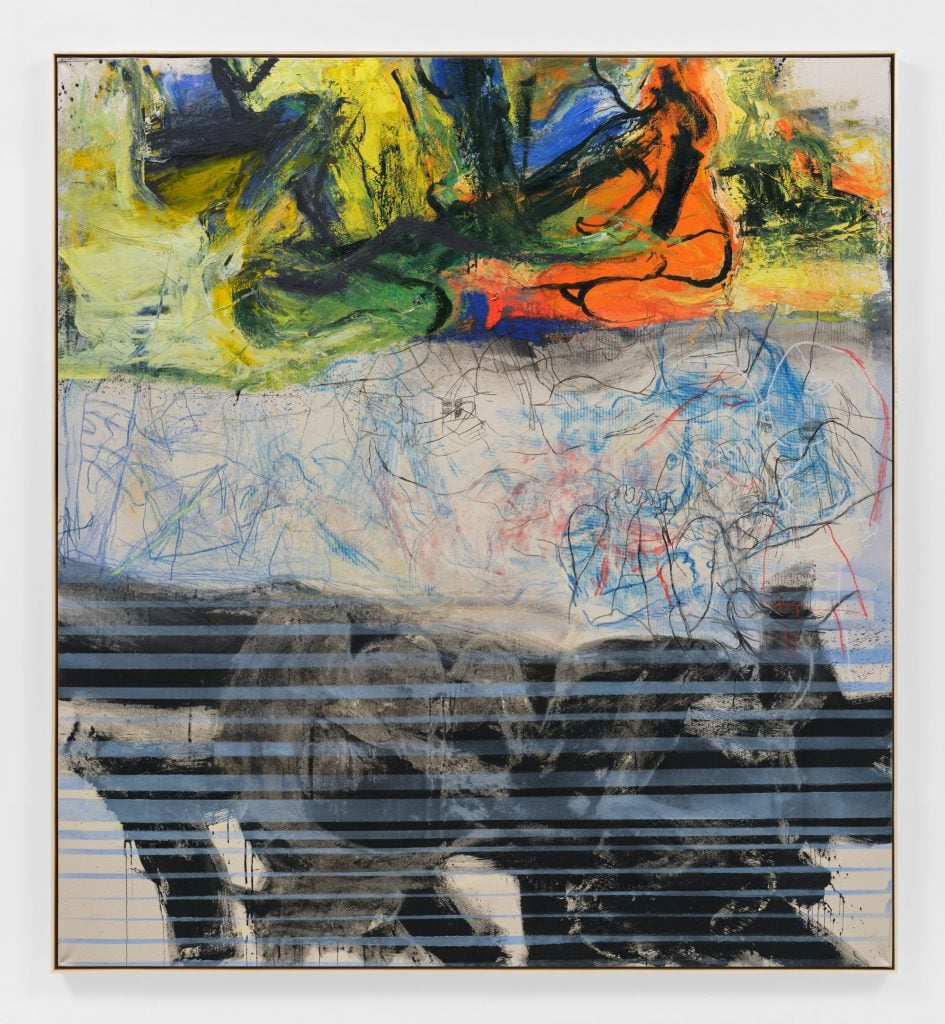

“Splits” is divided into paintings at the 22nd Street locale and screen prints on 18th Street. Hauser is also showing a brooding Ackermann painting at Frieze New York, the glowing outline of a reclining sprite superimposed over a storm of hues. In the body of work at 22nd Street, each canvas is divided roughly into thirds. Shutters features Cloisonnist contours filled with shocks of orange, yellow, blue, and green across the top; scribbles in blue, black, and red across the center portion; and the bottom is filled with inky black, almost like a Rorschach test, with uniform blue stripes then layered on top. This splitting—for me, evoking two eyelids opening and closing on a gazed upon scene—is consistent across the different pieces.

Rita Ackermann, Shutters (2023). Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer. © Rita Ackermann Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

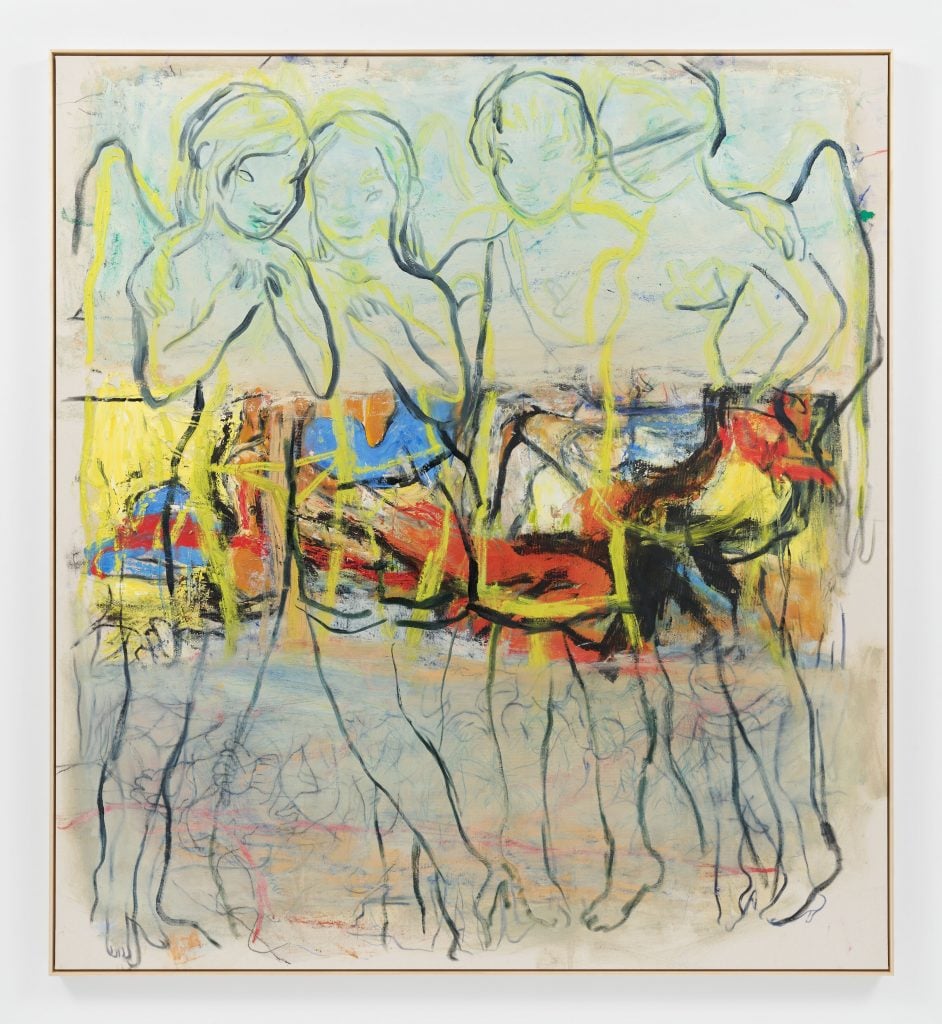

The disbursement of painterly color and more monotone scrawl shifts. Some works sketch vague figures. Without Narrative features four small bodies, forming a tight posse, arms around each other’s shoulders. They’re vaguely cherubs. Two have discernible wings while their almond eyes callback the fairytale ingénues of Ackermann’s work from the 1990s, in which similar characters were rendered with more cartoonish outlines. There’s a maturity that doesn’t feel contrived, a pensive moodiness, the feeling of calm within turbulence. During an artist talk Tuesday, Ackermann surprised her interlocutor, historian and curator Pamela Kort, saying she did want people to think her work is beautiful. It is.

Ackermann prefers to let her images speak for themselves. For an artist talk she gave to preview the exhibition, which runs until July 26, she made a montage video to play in the background hoping to distract and complicate her spoken explanations. For this somewhat diaristic film, she recorded off her computer screen favorite clips she’s been watching: among them, interviews with film directors Jean-Luc Godard and Robert Bresson, as well as footage of Michael Jackson dancing. When we spoke over Zoom, the artist wore a zip-up with “Angel” printed in varsity-style lettering over one breast.

Ackermann is endearingly stubborn and unflappably cool in how she avoids talking about her work. No bullshit artspeak here. During the week leading up to the show, we chatted about everything except the new split paintings, her foray into screen painting, or really much about process. What she did delve into includes cinema, freedom, perseverance, control, and hands. “Hands tell the truth,” Ackermann contends, “they probably know more about the person than the person knows of himself.”

Installation view, ‘Rita Ackermann. Splits,’ Hauser & Wirth New York, 22nd Street © Rita Ackermann. Photo: Thomas Barratt

The new body of work will soon be unveiled. Is the week before a show stressful?

No, no stress at all. Making art has never been stressful for me. And the installation was easy too, just nine paintings hanging on the wall. The real treat is seeing them together. They were made in two separate studios, so some of them haven’t seen each other yet. And that was interesting to watch. It was like when humans meet for the first time. The upstate team meets with the Brooklyn team. They have complimentary qualities and get along well.

I only get worked up if I have to go to the doctor or get ready for a talk or interview. In fact, I made a film for a talk. Did you have a chance to see it?

I just watched it.

Oh good, this film was made to release my nervousness of speaking in front of an audience. Because words are really not my language. The way words articulate my thoughts somehow comes out clumsy and I end up saying something different or even unnecessary and the important stuff stays inside. I don’t really speak well for my paintings. They relieve me from that stress of talking.

I liked the “listen to the image” quote from the video.

That quote is from Godard. He speaks so well on the paradox between sound and image. Have you heard of this book Duras / Godard Dialogues? It’s a recently published book on conversations between the writer, Marguerite Duras and the filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard. They had a very fruitful friendship for two to three years that was recorded in their works. Simply put, they inspired each other through exchanging ideas. Duras made films as well and Godard’s films were often text heavy – they discussed and set their conquest to experiment with either separating sounds and shots or mixing them up on the screen until they were indistinguishable. These methods felt familiar not only to the way I “montage” edited the film, but also to how my paintings go through stages of gestures and bodies to disappearance.

I wanted to make this film for my talk to distract the audience from listening to our conversation. The eyes will be glued to the images on the screen, interviews in French with subtitles, and sounds of music and meanwhile it doesn’t matter if I say incomprehensible or inarticulate things. The important punctual ideas which I would like to convey to the listeners, the subtitles in the footage, will be repeated on the projection behind us. The message of the film is to listen to the image and then listen to the paintings. Then we don’t have to explain them.

Rita Ackermann, Without Narrative (2023). Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer. © Rita Ackermann Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

As someone who often writes about art and pays a lot of attention to how art is put into words, it can be frustrating because so much is flattened. When people try to explain art like, this equals that, it’s like a butterfly you’ve pinned to a board. It’s dead.

I can’t agree more. It almost feels like a cruel deadly execution against the artwork when it is explained by the maker. You don’t have that feeling anymore that this work could live on its own or could be perpetually developing through the audience. Because, yes, an artist makes a work, but then the making doesn’t stop when the artwork is finished by the artist. Once it’s exhibited, it’s really in the making still with the viewers’ vision, and what the viewers add to it. And that’s the real mystery about the greatness of art.

If you think about it, why is there always a ring of admirers swarming around Van Gogh? Anywhere you go in a museum, the Van Gogh painting always has a circle of people around it.

I wanted to ask you about freedom or individuality. I feel like this is what Western culture values in the artist. People often say that you have a very free spirit. But I feel like this word “free” has also been co-opted by marketing. You also have stubbornness in refusing to explain your work and make it legible in this way the art system often rewards you for. There’s this demand to act a certain way which you don’t give in to. I thought you could describe it instead of freedom as resolve.

Can I ask you to give me the exact definition of resolve?

Firm determination to do something.

Is determination intuitive, you think? Maybe it is an instinctual virtue, something you can’t help but follow through with.

Installation view, ‘Rita Ackermann. Splits: Printing | Painting,’ Hauser & Wirth New York, 18th Street © Rita Ackermann. Photo: Thomas Barratt

To me resolve is a quieter determination that comes from your core.

Have you seen the movie, The Loneliness of The Long Distance Runner? It’s a really great old movie from the 60s, black-and-white. It’s about a working-class boy who ends up in a correctional institution where he trains for cross country and there are these long shots of him running in solitude. What captivated me about that movie was that he achieves a certain kind of freedom within himself in prison through this training that reaches a level of dignity. Even winning could not bribe him away from this introspective freedom. Anyway, I won’t give you the end of the story, but it’s all about the different nature of freedom and what you have to give up and what would be too much to give up for freedom. There is a paradox between captivity and freedom. It is hard work to be free not to be a slave to something or somebody. I grew up in communist Hungary where there were different ways of practicing freedom that didn’t cross the boundaries of the regime. We learned at a young age to achieve freedom not through external circumstances but through digging inward for freedom that was to be sought out, coded, and hidden. It was freer than any freedom that an external world could offer but you had to work for it and to be obligated to it. Arriving in New York from the disadvantages of oppression with the advantages of knowing the codes to unlimited freedom gave me tremendous independence. So I was able to utilize my obligation to that inner freedom I would say. I don’t know if it makes any sense.

No, it does. That there is freedom in discipline.

It allows you to do your thing to carve your own path with dignity and not to fall for slavish temptations of momentary success. I had a religious upbringing that helped to stay with my core belief. Spirituality gives you innate freedom. I look out the window and see all these desperate students protesting around the streets and campuses. They feel passionate about a cause that is not even theirs but it gives them a sense of belonging and purpose that masks itself in compassion and justice. Escalating boredom could get violent and culminate in suffering when nothing can fill the void that has no limits. Living without belief is like thrashing around, trying to grab on any external feed from the news or foreign affairs to fill a bottomless void that has nothing to do with freedom.

The artist Rita Ackermann. Photo: Daniel Turner.

What year did you arrive in New York and what was it like back then?

It was ’92. It was a good time to arrive in the city that was changing from glamorous decadence to deconstructivist grunge. It was not a problem not having money. Most of us had to hustle and be creative to get somewhere. It didn’t matter where you came from or what school you went to.

I left the Hungarian Academy for waitressing in New York. There was only one art school back then in Budapest but there was a very lively underground art scene. Curious people were coming from all over the world to mix and mingle. Post communism did not hit Hungary as hard as it happened in Russia. In the late 80s there was great local music, theater, and film that I was lucky to experience. Also, there was something about the language that united the Hungarians in their country and divided them from the outside world. But there were not many places in Hungary to look at art. We had only two fine art museums and of course no galleries.

In the 90s, you were really in this LES scene, which included Max Fish and Thurston Moore. Maybe it’s not the same as it was back then, but I still feel like the best stuff is always at these intersection points: art, music, nightlife.

New York City is completely different and then from another perspective it is very much the same as it was when I was beginning. I meet with young artists and gallerists through my daughter who is a painter herself. The city still operates on the footwork level if you choose to let spontaneity play a part in your plans. And there are young artists who choose to learn from older generations instead of spending a fortune on school. My friend Bernadette of Bernadette Corporation is working on her film with a 20-year-old filmmaker right now. He has such a crystal-clear vision. It is captivating when someone has an uninfected clean voice of their own. There is a timeless quality to innocence.

I spend a lot of time thinking about why this art works or this art doesn’t, and at the end of the day it really is about a clarity of vision. There’s so much content out there competing for your attention. But if you feel like someone really translates something only they could translate, it’s captivating. You really know something about them, even if it’s that they want you to know nothing about them.

It is awful when art is being explained, it almost feels dirty, like you would need to take a shower to wash off that sinful activity. In press releases and artist conversations and interviews, artists are forced into this situation where they have to give more and more and more information about process, material, and meaning or relations. What is important for me is the surprise of immediacy or rather a kind of self-entertaining spontaneity. It is more interesting to me to analyze films than art. I like to listen to what film directors’ have to say. Like Robert Bresson says that he ‘d rather have the audience feel than understand his film. To me, accidents are so loaded with intentions while premeditated moves are stabilizers.

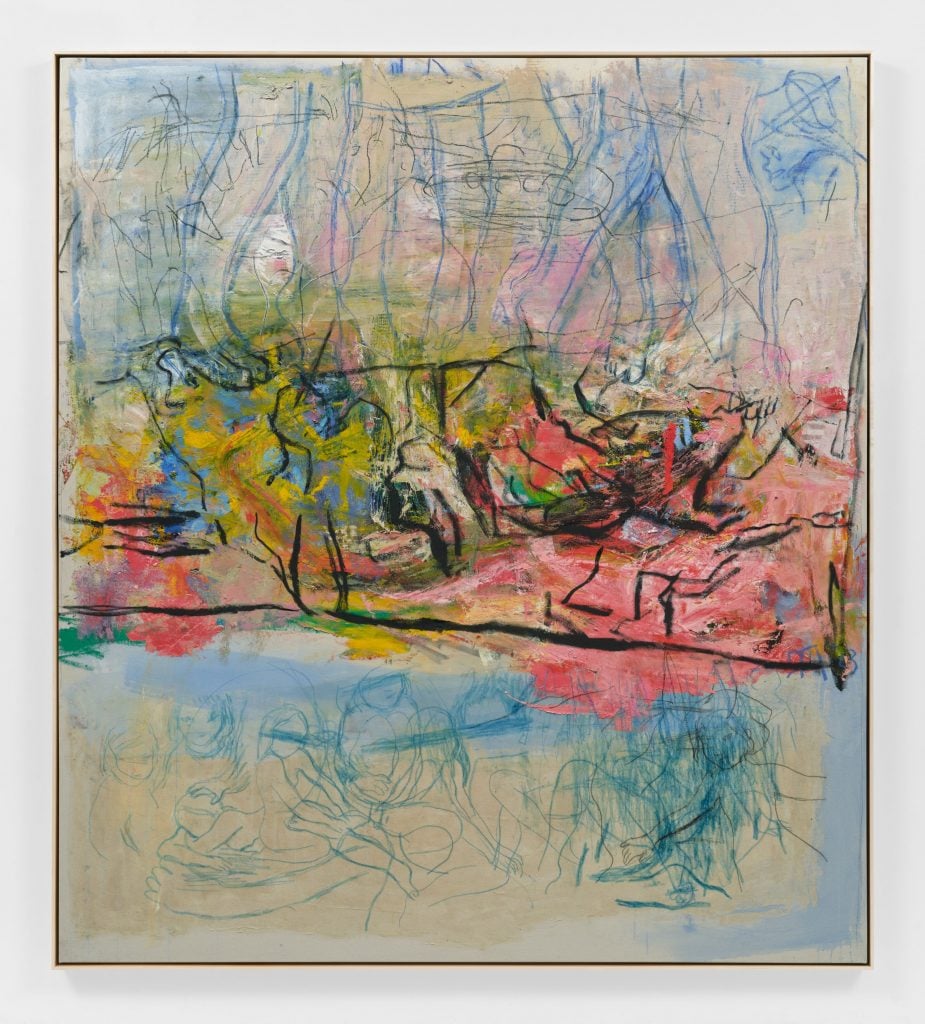

Rita Ackermann, Noisy Feet (2023). Photo: Thomas Barratt. © Rita Ackermann Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

In your early work, you had these characters, they’re almost in a world. And maybe we don’t know the sequence of events that transpired for them to get to this moment, the way we might in a novel or a movie, but we get a sense of this character and their world, but above all else, a mood.

In the early figurative works, I had a character which acted out multiple roles in different scenes. There wasn’t a clear narrative in the picture frame, but it was more like the stop edit style of a montage of scenes. And here when I look back at what I was exactly doing in those paintings it is somewhat clear that I was making a short film. And the picture was like an episode that might have continued on the next picture but there was no story that could be followed but rather as you said there was a feeling or mood that penetrated through them.

Years later, I was able to make sense of the early works I had made. When I got into this Hungarian director, Miklos Jancso’s movies and learned about his invention of track editing. You can see this method in Bela Tarr’s films as well, when they don’t cut from scene to scene but move the camera on tracks to follow the happenings. In a way, the early paintings were like track editing, moving the eye from background to foreground to follow the stills of different actions. You could also zoom in and out on these scenes, and there was no chronological order, all the happenings were stretched out in one singular frame. These works were compared to the style of Henry Darger’s storytelling, but I didn’t know about his work until someone pointed them out to me and I went to see them in person at an Outsider Art Fair. It was curious to discover odd similarities between his work and mine. But his realm was not made for the public eye while mine was made to be seen and heard, to communicate with the outside world.

It’s interesting how you can have this kinship without consciously knowing or having seen it. There’s a spirit that’s beyond us. I read that you said sometimes your hand knows more than what your mind knows what you’re going to create.

Yes, hands are more telling than the face. I always have an unshakable urge to draw hands. They narrate the unconscious when they gesture or doodle. Bresson only worked with non-actors and instructed them to be expressionless and monotone with their faces while their hands acted out the story. Hands tell the truth, they probably know more about the person than the person knows of himself. Directly wired to the essence of the person.

People call them “art talk hands” sometimes. I love these gestures. You see them a lot in these old school public intellectual talk show interviews. Like the ones in the video you made for your talk featuring Bresson and Godard.

Rita Ackermann, 10 Takes (2023) and 19 Takes (2023), editions of 15. Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer. © Rita Ackermann Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Yes, exactly. In video interviews the hand gesturing can be revealing or even distracting from what the person is saying. I wonder why Bresson was holding with both his hands a rolled-up newspaper during an interview? Video interviews are hard. People who are good at it must be putting some time into thinking how to sound and appear through cameras. It is a definite skill and a bit dangerous as well because, after all, it can override the purpose. I mean why does an artist have to be good at talking about art or herself in front of an audience? It is better not to get used to it. I don’t think one should get used to making paintings either. Every day is a radically new day in the studio. I would quickly get bored if I had everything planned and knew what was going to happen.

And I think a lot of what is “toxic” in our culture—sorry to use therapy language—is people not willing to give up control. But then as an artist at a large scale you have to control how your vision is executed. There’s contradiction in everything. But I wonder, do you think you’re controlling?

Especially since I asked for some pre-conditions to our zoom, I think this question is very valid! Yes, I’m controlling where or whenever control can be applied. But I strongly believe that it is impossible in the long run, for an artist to have control over how their works are perceived or even their career. And the more successful they are at controlling, the less their work looks like original art. This reverse effect is also true for art that is made to fit trends in order to gain recognition because eventually the short circuit trends reign over the artists. Art supposedly mirrors its society and even it can foresee what it is heading toward. We might be living in a moment when the fight for complete control is out in the open. And who knows how it’ll play out in contemporary art. If we detached from trends like activism, therapy, and craft, art would be less available, and in a way, less controllable. Quality has a tendency not to be inclusive therefore mediocrity should replace it conveniently. It is almost comical to see how the overcompensation for equality and diversity in arts adopted a certain aesthetic of individualism that became like a uniform which was mandatory in totalitarian societies. It’s crazy to watch how the tactic of controlling is executed with flipping over reality. But after all from a higher perspective, eventually all these forces blurring what is real in order to take control will bite their own tails. If you are people pleasing, you can also be easily controlled.

We might bicker about definitions like what is art and what is craft, but I think there’s some collective understanding that contemporary art is supposed to be challenging in spirit. Taking a risk.

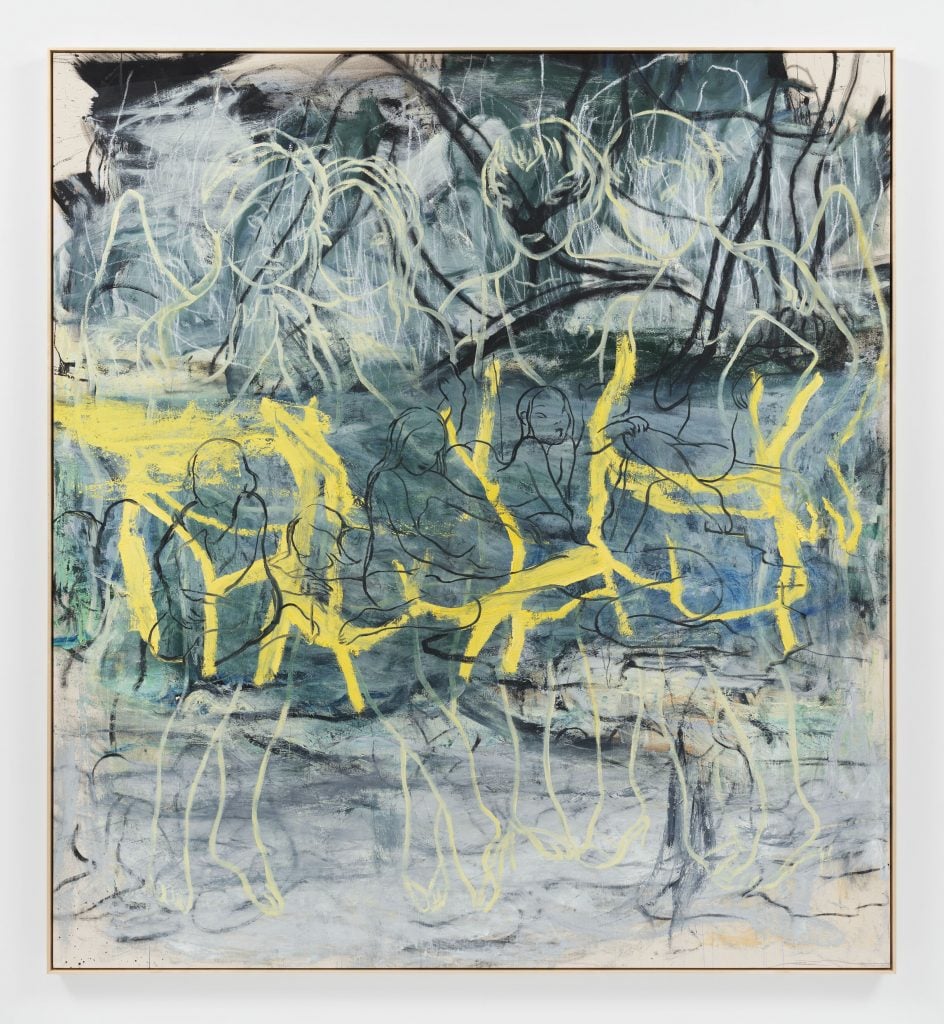

Rita Ackermann, Reversed Angles (2023). Photo: Sarah Muehlbauer. © Rita Ackermann Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Do we live in such “fast and conservative times” that young artists are fearful to take risks? There are brilliant talents out there who are getting recognized and hopefully they are able to resist all kinds of pressure from the industry. The number one pressure is overnight success itself. And this takes us back to the beginning of our conversation about persistence. How can one develop a style and not be afraid to break away from it when it is time for a change? To follow the urge to experiment when the outside world demands the same? Being obligated to freedom helped me stay on the path which is nobody else’s but my own.

Social media is an uncontrollable monster. In my opinion nobody who uses it can stay sober. When you are engaging on social media, and you are not lifting from the social or marketing platforms, you get sucked into a vacuum like the black hole. You are just sprinting and spinning with everybody and everything all together in some kind of purgatory. And then there are the angels who are fighting to save the souls.

It’s like a gladiator duel.

Yes. It is definitely a dual time for heaven on earth.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.