Reviews

How One of the Greatest Photographers Turned Against Photography

The U-turn at the heart of “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue” at MoMA.

The U-turn at the heart of “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue” at MoMA.

Ben Davis

I do love The Americans. When I’m feeling pensive, sometimes I open the book, and every time I find in Robert Frank’s photographic catalogue of ‘50s America a feeling of clarity about how to look at the world, something to take me out of myself.

I can already imagine the curators of MoMA’s lovingly assembled “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue” frowning at this intro. The exhibition’s selection of 200 works is about just about everything but The Americans, the six decades of work that Frank did after that classic achievement.

Not having it in the mix is a little bit like a band refusing to play its biggest hit, but I actually appreciate the desire to focus on lesser-appreciated material. The reason I bring it up is that I think to understand what Frank was up to, it helps to know not just what he was trying to do, but also what he was trying to undo. And one of the things he was trying to undo was The Americans.

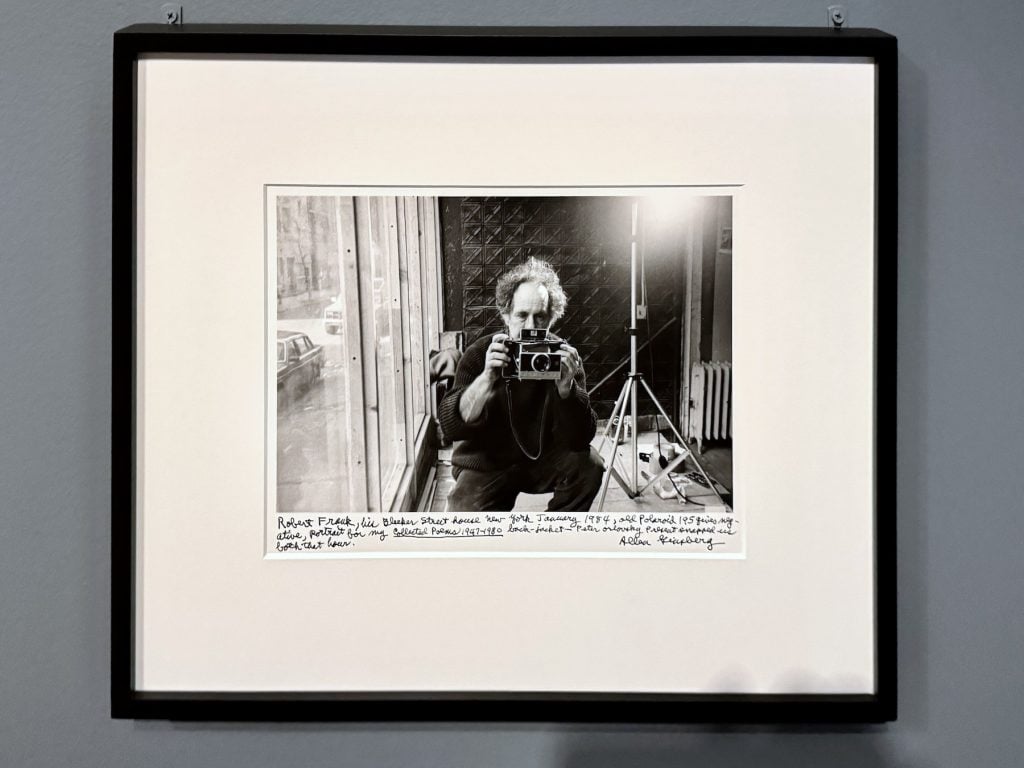

“Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue” at the Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Ben Davis.

Frank, who died in 2019, was born in Zurich in 1924. He apprenticed with photographers in his teens, so when he moved as a young man to New York, in 1947, he already had chops. He got work for Harper’s Bazaar doing light editorial work, but it was two Guggenheim grants that let him go on the 30-state road trip in the mid-‘50s that formed the foundation for The Americans, with its gorgeously forlorn vision of the United States in the Eisenhower/McCarthy era.

Some early critics thought it was a foreigner’s unflattering take on his adopted home—funny now, because what stands out is how equipoised its mixture of alienation and tenderness is, how much poetry Frank gets from the materialism of midcentury U.S.A. Back in New York, he was part of the artist crowd around the Tenth Street galleries and the Beats, and MoMA’s show contains plenty of his images and collaborations with each. Writer Jack Kerouac, then at the peak of his post-On the Road fame, would do the book’s introduction, and The Americans took on a reputation as a definitive document of its time.

This is more or less where “Life Dances On” starts. Among its first highlights is a fine series called “On the Bus,” which was first shown at MoMA the same year The Americans was published, in 1958. Superficially, it is similar: a sequence of images in the same gorgeous gelatin silver tones showing ordinary characters on the street, here shot from the window of a bus going down Fifth Avenue.

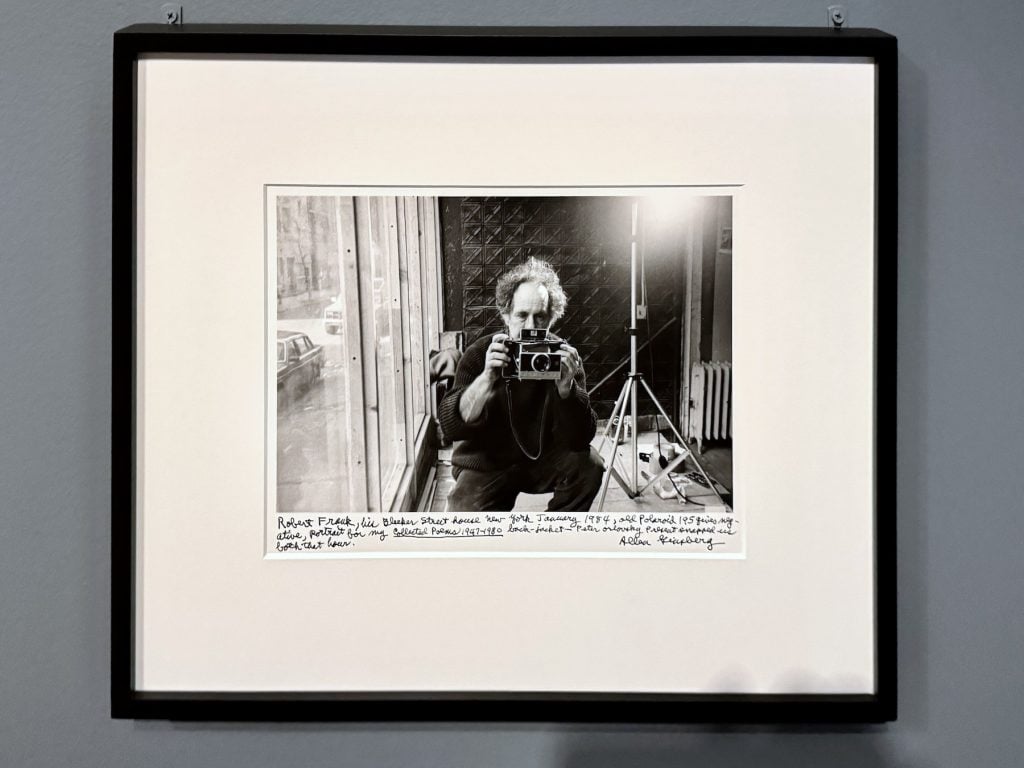

Two works from Robert Frank’s “On the Bus” series (1958) in “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue.” Photo by Ben Davis.

But it’s very different. For all its everydayness, and its similar-seeming obsession with shooting from moving vehicles, The Americans was artfully sequenced and composed, each image striking a perfect, clear note that builds into a (minor-key) harmony. The “On the Bus” series aspires to being a field recording rather than a symphony, a document of passing through a place at a specific moment. Frank saw “On the Bus” as the end of something and the beginning of something else. It was.

From then on, Frank began to exit conventional documentary photography. I cannot think of any other artist whose public profile shifted as dramatically, from being seen as popularly resonant in a Voice-of-a-Generation way to being seen as intensely hermetic, a complete artist’s artist. (Although his Beat cachet would bring him work shooting the Rolling Stones for 1972’s Exile on Main Street and Tom Waits for 1985’s Rain Dogs, which get their due in displays.)

Images of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards by Robert Frank displayed in “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue.” Photo by Ben Davis.

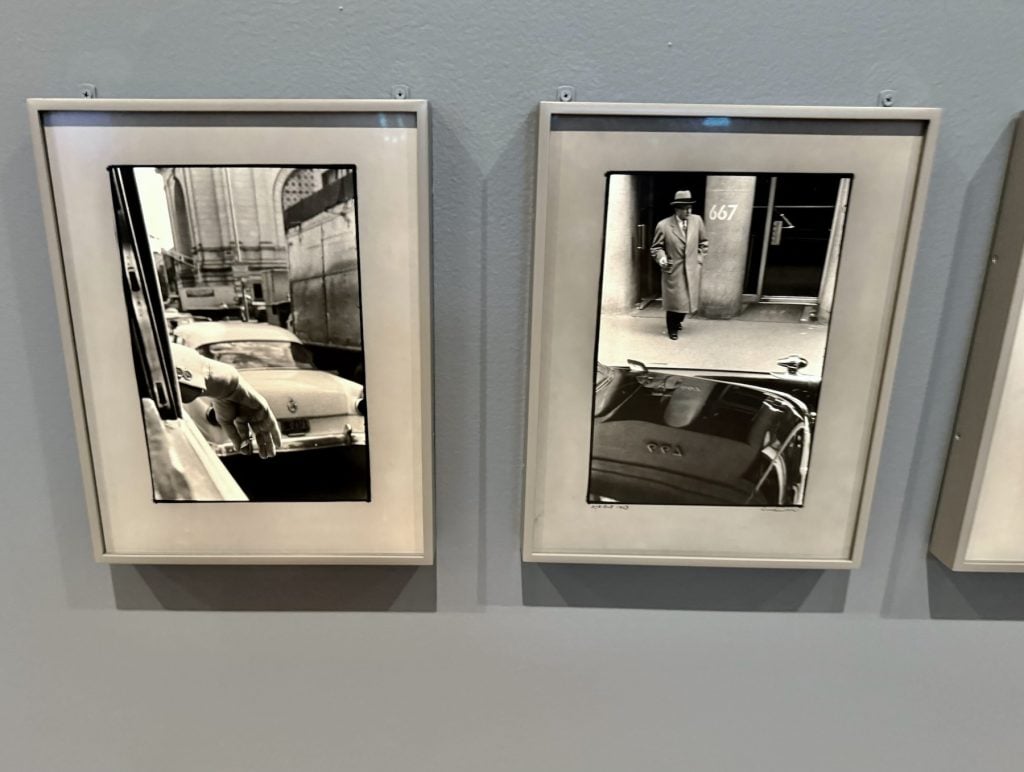

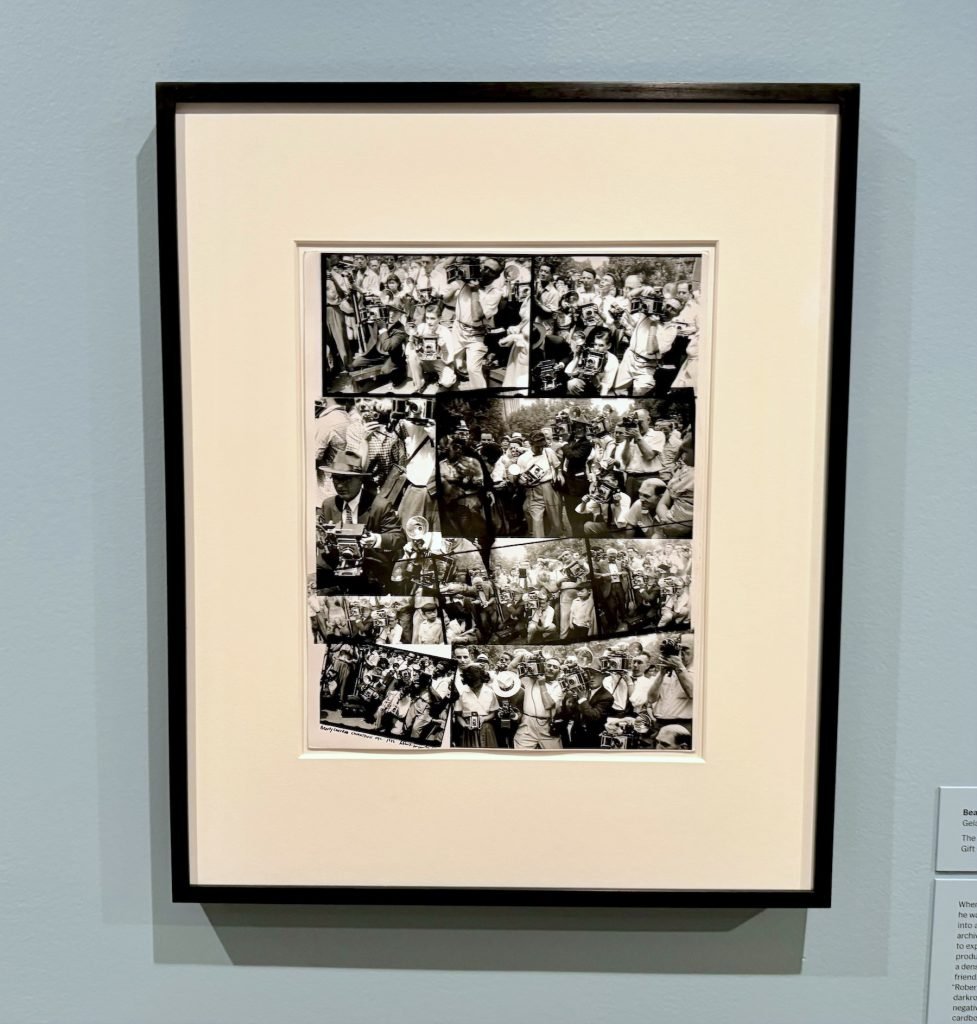

Frank’s process of editing The Americans involved making 1,000 work prints from 767 rolls of film before making his final selections. You often see his contact sheets reproduced in discussions of the work—all the alternative angles on some scene and then the one famous image from the 83 in the final book, marked out by a red circle (the National Gallery of Art has some you can look at online). Notably, there are later works in “Life Dances On,” like Beauty Contest, Chinatown (1968), with its multiple stacked serial images of the same busy scene, that evoke exactly this raw visual source material.

Distilling a long, lonely process of looking down to perfect, gem-like moments, Frank had created one of the great, magnetic accounts of postwar ennui—but thereafter it was as if he wanted to reverse the achievement by trying to welcome back into the picture all the life that he had previously edited out. The animating belief behind all of Frank’s experiments post-The Americans is that such documentary images participate in the alienation they document, rendering life cold.

Robert Frank, Beauty Contest, Chinatown (1968) in “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue” at MoMA. Photo by Ben Davis.

Thus, the world-in-motion of “On the Bus” augured Frank turning to the moving image, mainly to odd and difficult art films. The first of these, Pull My Daisy (1959)—shown via a clip and a cluster of stills—was a collaboration with artist Alfred Leslie. It features narration by Kerouac laid over somewhat shapeless scenes of an apartment meet-up of art people. The cast included poets Allen Ginsburg and Gregory Corso and painters Alice Neel and Larry Rivers. Coming after Frank’s deep and deliberate marination in alienation, Pull My Daisy is most interesting in the way it reads as an almost theorem-like reversal, making a direct virtue of intimate community and messy conviviality.

As for Frank’s subsequent non-moving-image work—the bulk of this show’s cargo—he made photo collages (like Pablo and Sandy, 1979) and landscapes assembled from multiple stitched-together pictures (Mabou Mines, 1971-72). He photographed his own photographs, hung from clotheslines in nature, thereby literally animating them with the surrounding environment (Bonjour—Maestro, Mabou, 1974). He did a lot of scratching lines or scrawling words directly onto the image surface, emphasizing its psychological character (Hold Still—Keep Going, 1989). He spent a lot of time on correspondence that itself can be seen as diaristic mail art (Sarah Greenough has a lovely essay about this in the catalogue).

Frank’s change of style coincided with a change of content and scenery. After making his name documenting the United States of America, Frank moved to the tiny rural community of Mabou, far out on Cape Breton Island in the east of Canada, in 1970. (An image of a wispy, almost-alive snowdrift swamping a Nova Scotia landscape from 1981 may be the most visually arresting in the show.) From his sprawling, restless tour of the byways of the U.S., he went to rooting in small-town life. Late in life, he made a film that simply followed along on the local paper delivery route, much to the bemusement of fellow Mabou residents, who weren’t sure why this was interesting.

Robert Frank, Storm in Mabou, New Year (1981) in “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue” at MoMA. Photo by Ben Davis.

Most importantly in terms of Frank’s reversals and negations, The Americans was read as the emanation of a collectivity as much as a product of a personal vision (as the title suggests). It was first published in a French version as Les Américains, with Frank’s pictures accompanied by quotations from the likes of Benjamin Franklin, Walt Whitman, and Richard Wright—textual ornamentation wisely eliminated from the U.S. version to allow the images to speak on their own and of their moment. By contrast, almost all of the work in “Life Dances On” feels turned away from social life, deeply in Frank’s head—even when it is literally looking out the window. Landscapes, interiors, and still lifes are all presented as containers of intimate, half-divulged symbolism.

In Laura Israel’s documentary about Frank, Don’t Blink (2015), you see footage of him addressing a college class in the early ’70s. He fields a question about why his work has become so hard to penetrate. “I am looking for something,” he says defiantly, “and if my films are in no way as successful to almost all people as my photographs are, it just makes me look harder, to express it stronger and better. Maybe I’ll never get there. I’m just happy that I am looking for it.”

And Frank did seem, on some level, to find happiness in his journey inwards. If “Life Dances On” nevertheless leaves behind the impression of melancholy, it’s because life itself remains stubbornly full of sorrow.

Frank outlived both his children. His son, Pablo, suffered from schizophrenia and died by suicide, in his 40s, in 1994. His daughter, Andrea, lost her life in a freak plane crash, aged 21, in 1974.

As I left the MoMA, I thought suddenly of one of the better-known images in The Americans, titled Crosses on Scene of Highway Accident, U.S. 91, Idaho: scrubby grass, a placeless stretch of road, and three small cross-shaped markers crudely mounted on pieces of rebar thrust into the earth. It’s powerful because the memorial is so anonymous and so unremarkable. A flare of light descends from the sky, seeming to intimate something spiritual. But because the crosses are angled away, the feeling the photo conveys is of them being sped past, forgotten at the moment of their revelation, memory a victim of the same speed that kills.

Robert Frank, Mabou (1977), showing his personal monument to his daughter. Photo by Ben Davis.

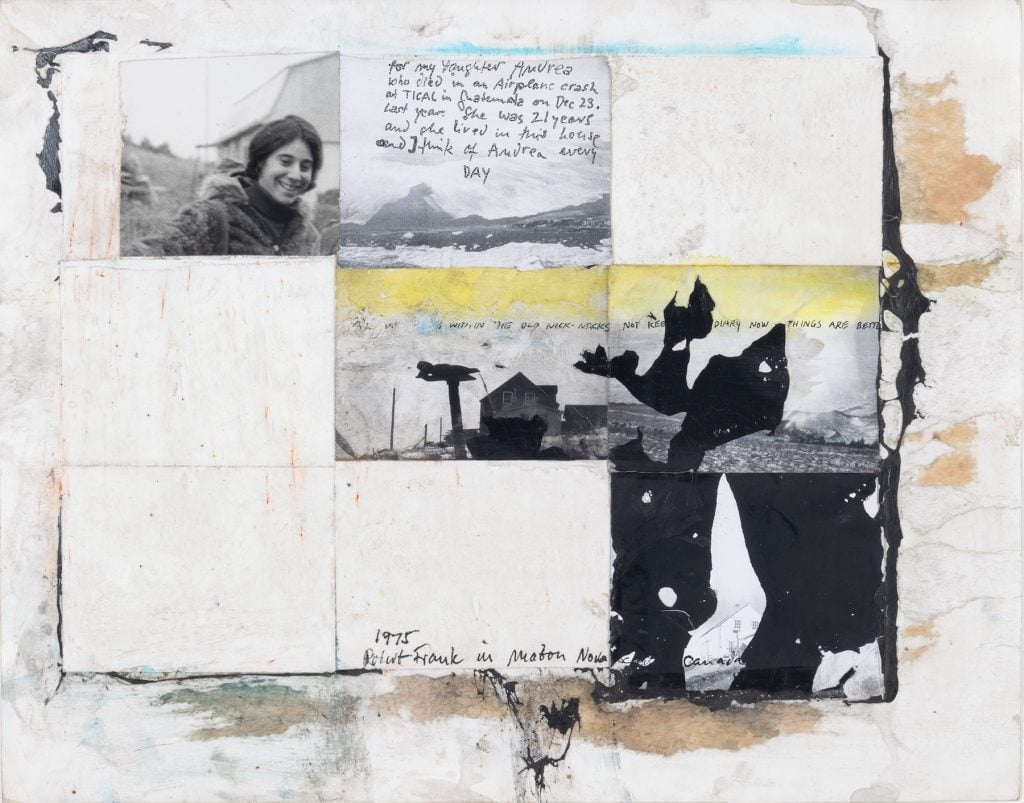

Two decades later, Frank would make a series of works to memorialize Andrea. Some, in mournful black and white, show abstract shapes, evidently bits of wood and stones he built up in the landscape as a personal mourning ritual, then photographed to give them permanence (his exact explanation, quoted in the catalogue, remains a bit obscure to me). Another, a collage, features a photo of Andrea smiling, inset in a grid. Some of its squares are blank; some contain hazy picture fragments adding up to the outline of the family’s Mabou house. And in one of the squares, Frank has written these words: “for my daughter Andrea who died in an airplane crash in Tical in Guatemala on Dec 23 last year. She was 21 years and she lived in this house and I think of Andrea every day.”

Frank’s photos of the improvised memorials feel so personal as to remain mysterious. But the collage with her face is so direct that it is almost like witnessing unprocessed grief or reading a page from a diary.

As an image, that sad roadside memorial from The Americans is the more reverberant testament to the modern experience of death. But as a form of coping with that experience—of inhabiting a consciousness that actually refuses to speed away from the tragedy—the Mabou works are the more meaningful. Their imperfection is something like the beautiful unguarded ugliness of someone’s face as they let themselves weep.

Robert Frank, Andrea (1975). The Museum of Modern Art, NY. Gift of the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation in honor of Clément Chéroux and Lucy Gallun. © 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

If I’m honest, I still prefer the worldly lucidity of The Americans as art. But “Life Dances On” makes me appreciate the fact that Robert Frank did not content himself with documenting alienation. He tried to pose a personal answer to it. And it is poetic to think that the artist who made what is likely the definitive roadtrip photo-book came to the conclusion at the end of it that the journey is the destination after all.

“Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, September 15, 2024–January 11, 2025.