Artists

‘I Can Do Whatever I Want’: Robert Longo on Grappling With Heavy Politics and Delicate Beauty

The artist and filmmaker has a new body of work on view at Thaddaeus Ropac and Pace during Frieze London.

The artist and filmmaker has a new body of work on view at Thaddaeus Ropac and Pace during Frieze London.

Emily Steer

It is impossible to view an image in total isolation. In an unavoidably digital world, we are used to seeing images as part of a chaotic mass. On top of this, each one comes loaded with an abundance of pre-existing connections and projections, both personal and collective. This is rich territory for the masterful visual manipulator Robert Longo.

For his new two-part exhibition at Thaddaeus Ropac and Pace in London, the U.S. artist returns to the ‘Combines’ format he first explored in the 1980s. Within two central works in “Searchers” (on view until November 9), the violent and political collide with the commercial and aesthetic, underscoring their inherently entangled nature.

“Those early ‘Combines’ were like sentence structures,” said Longo in an interview as the exhibitions opened. “There’s a verb, a noun, an adjective. There was always some weird narrative in my mind, but I wanted to make that quite difficult to read.” He was inspired to revisit this format when he noticed the powerful effect of a four-part archive piece, Master Jazz (1982-3), as it was shown in Walter Hopps’s exhibition with the Menil Collection (2023). This work reverberates with the silent scream of the central close-up face, which sits between a skyscraper, two suited figures, and a sleeping woman.

Untitled (Pilgrim) (2024). Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Robert Longo: Searchers, a two-part exhibition Thaddaeus Ropac, Ely House: October 8, 2024—November 20, 2024. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery, London · Photo: Eva Herzog

His two new “Combines” works, each seven feet wide, are comprised of five individual pieces that loom like billboards. At Ropac, Untitled (Pilgrim) features a luxurious rendering of a Chanel diamond necklace. Its oversized jewels twinkle alluringly against a slick black background. To its left, a video of fire rages behind a cage-like silver frame. Untitled (Pilgrim) also includes an intricate charcoal rendering of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s emotionally ambiguous marble sculpture Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647-52); a collection of 3D-printed twigs, enlarged and painted to read as branches; and a vibrant blue photograph of an iceberg melting. While the gallery viewer should probably pay more attention to the icecap, the eye keeps sliding back to the sparkling jewels. The Chanel necklace is taken from an advert that Longo found wrapped around the New York Times. He was struck by this image of glossy commerce covering devastating global news.

Each of the five panels represents a different form of art—drawing, painting, video, sculpture, and photography—although Longo renders them slippery. The Chanel panel, for example, at first appears to be one of the artist’s meticulous charcoal drawings. Then its gloopy surface comes into view, and it seems to be a painting. It is, in fact, a high-gloss print of a painting covering layers of newspaper. An image of the American flag is hidden within this dark void, as well as Margot Robbie’s Barbie. “Fake news!” he laughed, standing in front of this print of a painting of an advert. “Art is all a point of view. I want to undermine the idea of authenticity.”

Still from Untitled (Image Storm, July 4 – October 8, 2024; Chapter One) (2024). © Robert Longo. Courtesy Pace and Thaddaeus Ropac gallery

‘Let Me Go at It’

There is no getting away from the fact that these challenges to commerce are commercial objects themselves. Most of Longo’s record-breaking sales have happened since 2000, with his most expensive Untitled (Leo)—an intensely detailed charcoal drawing of a tiger’s face—selling for just over £1 million through Christie’s in 2013, the same year it was made. His record ‘Combines’ piece, Final Life II (1982-84), sold for over £500,000 in 2015. His work continues to surprise at auction—just this month, Untitled (Black Tube) sold for $361,600 at Christie’s, 30 percent higher than its estimate.

In our conversation, he reflected upon how the focus of selling work has changed since he began practicing with little expectation of commercial success. He does enjoy how this aspect of the market further drives the creation of the work. “When I made the ‘Combines’ back in the old days, I still worked with the same guy James Shepherd in my studio, and we would just piece shit together. We had no money. There was the theory that we couldn’t spend more than a third of the money we’d made from selling it. Now, I’ve got money, and I can do whatever the fuck I want! Let me go at it.”

While each of Longo’s images appears to have been meticulously selected, he likens his approach to the instinctive mark-making of abstract painting. This was clarified for him while watching a documentary about one of his idols, Joan Mitchell. “I remember thinking, ‘the choices I make with these images are on that same visceral level. Her paintings were like knife fights.’” He looks to many artists, writers, and filmmakers for inspiration. He returned to John Berger’s classic “Ways of Seeing” while making pieces for “Searchers,” as well as Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory.

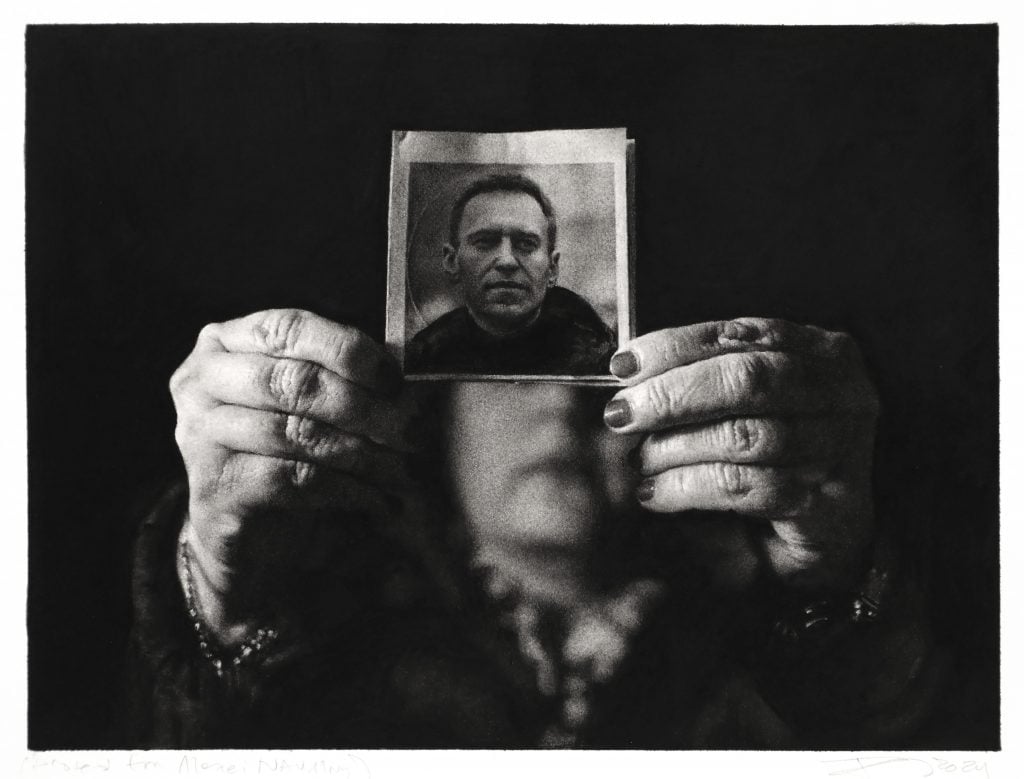

Robert Longo, Rally for late Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in Athens, Greece – 19 Feb 2024; Based on a photograph by Kostas Tsironis, 2024. © Robert Longo / ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery.

Epic Art

Longo’s own experience of seeing also drives the work. He has a particular interest in the relationship he had with images as a child in Long Island. “I was raised on black-and-white television, Life magazine, National Geographic, comic books. I loved all those epic movies like ‘Spartacus’, ‘The Ten Commandments.’ As an adult, I realized I’m trying to make epic art… There’s this period between nine and 12 or 13 years old where you go from being a boy who is playing to showing real aggression. It’s primordial, and I think everything comes from that. When I look at Untitled (Pilgrim), I can see when I played with my sister’s jewelry box. Or when I set fire to a field next to my house by accident.”

He describes the new “Combines” works as gendered, with the feminine expression at Thaddaeus Ropac and the masculine at Pace. Untitled (Hunter) (2024) is richly saturated in black, blue, and red. Its five frames include an extreme close-up of Keanu Reeves pointing a gun at the viewer from the movie ‘John Wick;’ a densely packed sculpture of jagged Plexiglas shards; and a grainy image of refugees at the Belarus-Polish border, with sharp coils of barbed wire in the foreground. Across the two galleries, these works toy with overt and covert violence, using seductive aesthetics to distract from or enhance their political undercurrents. Longo compares the eye’s movement between these images with the experience of flicking through channels, perhaps lingering on a moment of impact.

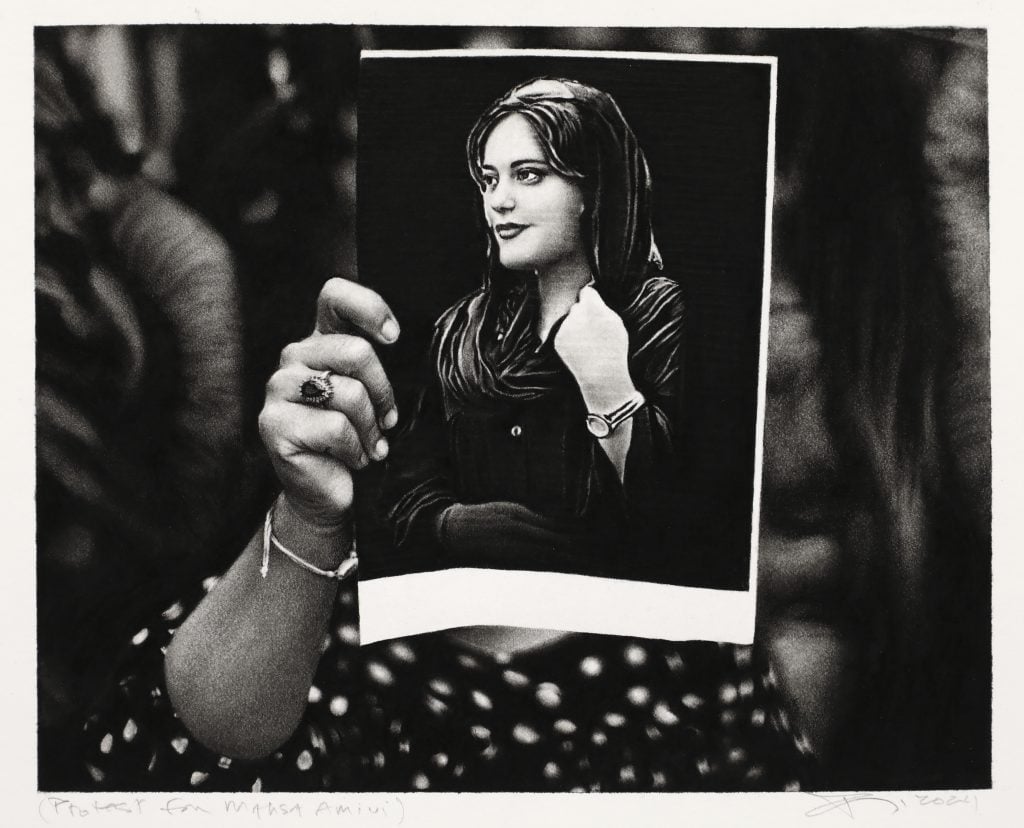

The exhibitions each contain an intimately scaled drawing of a woman’s hands holding up a photograph. At Pace, Untitled (After Navalny) (2024) shows an image of the murdered Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. At Ropac, the unidentifiable fingers clutch a photograph of Mahsa Amini, who died in Iranian police custody, triggering the protests of 2022. “It’s such big subject matter to be shown this small,” Longo said. “I want these images to haunt the whole gallery. All this shit is happening [gestures to other works], while this is going on over here.”

Robert Longo, Untitled (Mahsa Amini), 2024. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul. © Robert Longo / ARS, New York 2024

From Kamala Harris to the Euro Cup

Downstairs at Pace, Longo’s video work fills an entire wall. It features an overwhelming flood of images drawn at random from the internet between July and October 8. The piece runs at 100 frames per second, pausing occasionally on a single image before moving on. It makes a dizzying impression, not just on the eyes, but also the mind and body. “I was thinking of having a drum solo soundtrack, but I realized this is loud enough,” said Longo. He chose a monochrome filter for all the images to reflect the palette of dreams and memories. “It’s more abstract in black-and-white. When you watch it becomes like this weird Jackson Pollock painting.” As viewers move closer to the projection, the images begin to fall away into a profusion of frenzied pixels.

During our visit, this reel of images was dominated by the faces of Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. This omnipresence of the U.S. election cycle was broken momentarily when the video paused on U.K. soccer star Jude Bellingham’s Euro 2024 bicycle kick. For some English viewers, this photograph is rich with emotional significance; a much-needed, last-minute equalizer against Slovakia. Fittingly for Longo—though he didn’t specifically choose this image—the photograph went on to have a life of its own, with Bellingham’s mid-air Adidas football boot being quickly repurposed into an ad campaign for the brand. Despite the work’s random nature, this moment highlighted quite how much meaning can become attached to a photograph, calling to mind, in a split second, a string of other connections.

Robert Longo, Untitled (Hunter) (2024). © Robert Longo / ARS, New York 2024. Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery

Longo notes that in his lifetime, communication has expanded from black-and-white television, to limited color channels, then increasingly more frenzied and abundant as we find ourselves in the post-internet age. His work revels in the resulting visual chaos and also questions how these haywire means of information sharing dismantle the idea of objective truth. “Americans had this united idea of ourselves courtesy of World War 2, that we helped save the world. Now we have social media and the internet, we know more about each other, and we realize that we really don’t like each other. It’s not one country. You can’t hold this single idea of America anymore.”

As his career has progressed, Longo’s idea that we are moving towards a certain future has also been upended. “There are all these assumptions we have when we’re younger. But technology that looked like it would save us is actually going to kill us. One of the things I remember so distinctly is the feeling that I was moving into the future. Now I realize the future comes at us, and it changes the past. I’m old enough now that I have a collective memory that sometimes weighs heavily, and the future looks really fucking bleak.”