Archaeology & History

Were Ancient Peruvians High When They Made These Rock Carvings?

Toro Muerto is a rock art complex made up of 2,600 petroglyphs.

A pair of polish archaeologists believe geometric markings that appear alongside anthropomorphic figures on rock carvings in a valley in southern Peru may been representations of songs. What’s more, they may have been created during rituals that involved hallucinogens.

Since 2015, Andrzej Rozwadowski and Janusz Wołoszyn have been part of a Polish–Peruvian collaboration centered on Toro Muerto, a rock art complex comprised of roughly 2,600 petroglyphs. Some petroglyphs are small stones with a single motif, others are giant boulders with complex and diverse images.

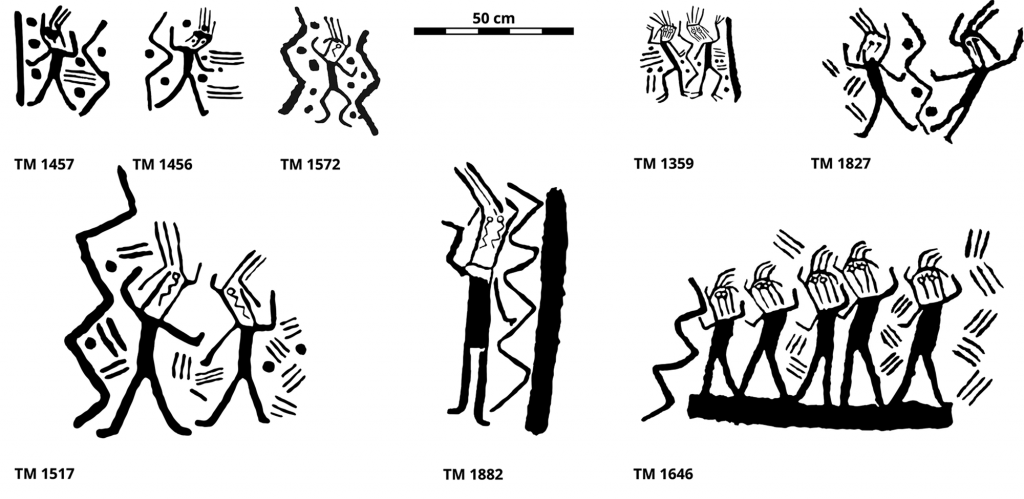

Variety of danzantes in Toro Muerto as compiled by Polish-Peruvian research team. Photo: J.Z. Wołoszyn.

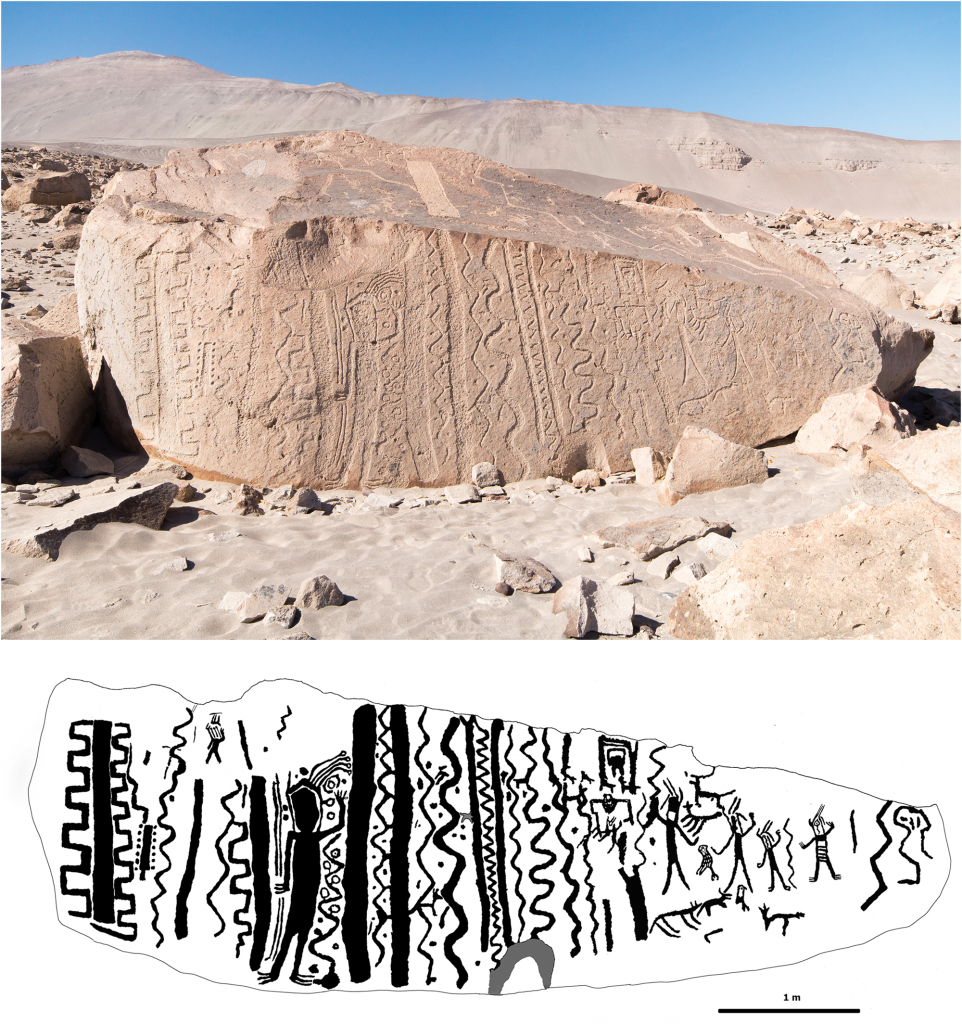

The most recent research was largely focused on TM 1219, a 16-foot long rock with numerous carvings dating back 2,000 years. The Peru findings were published in Cambridge Archaeological Journal on April 3.

TM 1219 depicts a scene of numerous geometric motifs, two birds, five quadrupeds, and six danzantes, one large and five small. A danzante is an anthropomorphic figure in a dynamic dancing pose. Exceedingly rare at other rock art locations, it appears on around 20 percent of Toro Muerto’s rocks and is considered the site’s central icon.

“No other boulder gives the impression of such a coherent arrangement dominated by linear geometric motifs,” the researchers wrote. “The suspicion is that this stone may have been of special significance in Toro Muerto.”

Boulder TM 1219. Photograph: A. Rozwadowski.

The research was focused on understanding the relationship between the danzantes and the accompanying linear geometric motifs. Previous rock art research from across the world had found markings evoking the sounds produced by animals, human breath, and human speech. In Peru, research has also suggested that zigzags associated with the dancing figures may symbolize snakes or lightning.

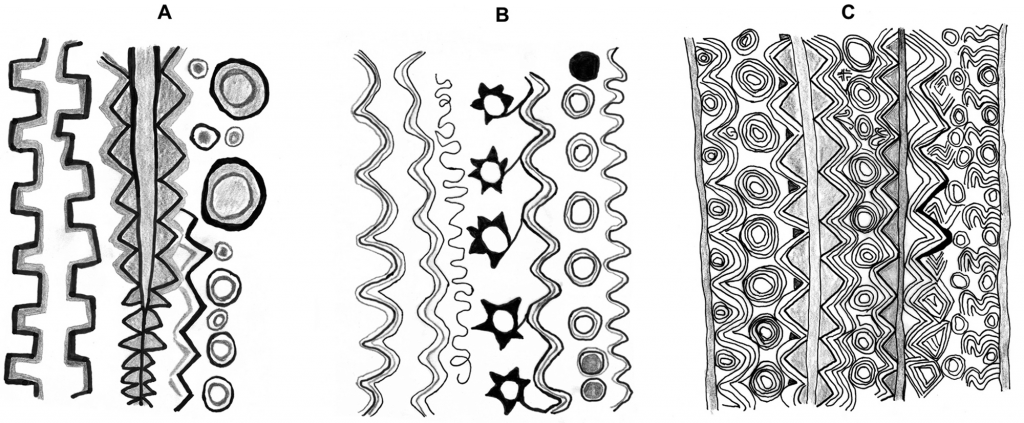

Rozwadowski and Wołoszyn, however, were drawn to the studies of Tukano carvings in the Colombia rainforest by Austrian anthropologist Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff that took place in the 1970s.

The Tukano carvings similarly featured anthropomorphic figures surrounded by circles, dots, wavy lines, and zigzags. Reichel-Dolmatoff interviewed local informants who revealed that they were yajé images, meaning those made under the influence of the yajé psychoactive drink. The scenes on the Tukano carvings referred to stories of the world’s creation, myths the peoples returned to during rituals with dance and song. The Tukano saw the geometric patterns as representations of singing that took place during such rituals.

Redrawing of three Tukano drawings collected by Reichel-Dolmatoff in 1978. Photo: A. Rozwadowski.

Rozwadowski and Wołoszyn’s assertion is that the motif was fairly universal in the iconography of pre-Columbian America and that the behaviors of the Tukano can be extrapolated to Toro Muerto.

“The construction of this motif may have been a matter of convention, and the representation of an idea known more broadly and earlier—that is, not a one-off interpretation proposed by Reichel-Dolmatoff’s informants,” the researchers write.

If correct, it would confirm the notion of Antonio Núñez, a celebrated Cuban geographer and archaeologist who was ambassador to Peru in the 1970s. Núñez was one of the first to research Toro Muerto and called for it to be placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. He suggested the geometric motifs might represent musical or dance signs.