People

Auguste Rodin and Rainer Maria Rilke Had a Strange, Moody Friendship

Rachel Corbett's elegant 'You Must Change Your Life' traces the paths of the sculptor and the poet.

Rachel Corbett's elegant 'You Must Change Your Life' traces the paths of the sculptor and the poet.

Jonathon Sturgeon

Empathy—the idea, the thing itself—whirls through Rachel Corbett’s elegant new study of Auguste Rodin and Rainer Maria Rilke like a wind. After all, the title of book, You Must Change Your Life, which comes from Rilke’s famous “The Archaic Torso of Apollo,” implies a measure of empathy: you only tell someone to change if you care about them. Rilke and Rodin, it turns out, cared about each other in strange ways.

The relationship between the master sculptor and the pupil poet, we learn, was both tempestuous and tranquil. There were gusts of empathy between the two men at times, coming especially from Rilke’s direction; at other moments: the stale air that arrives with hurt feelings and broken promises.

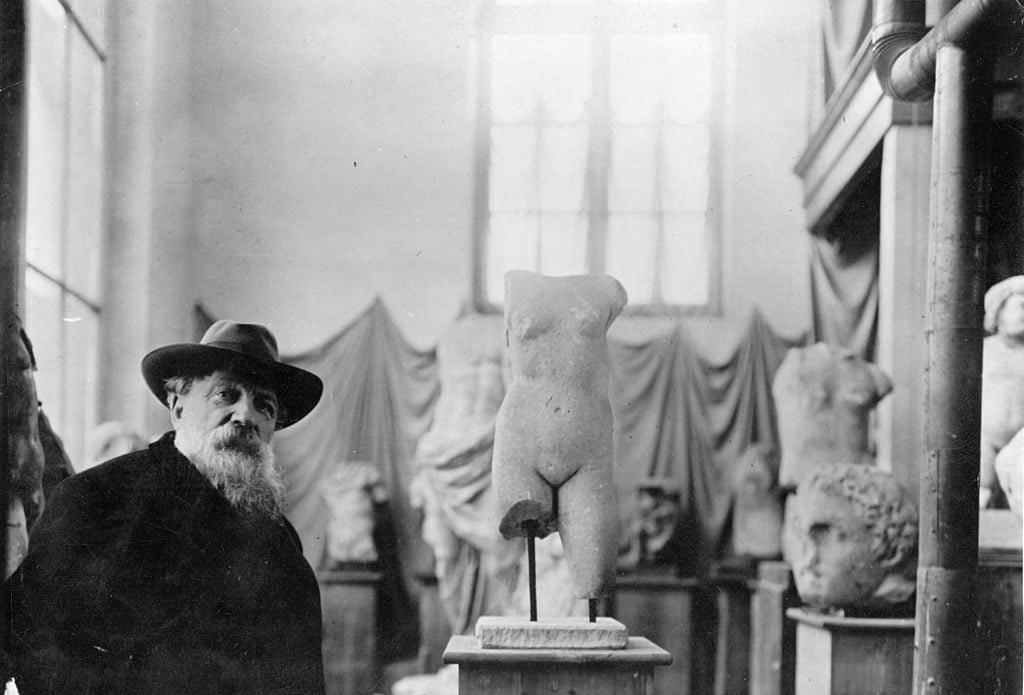

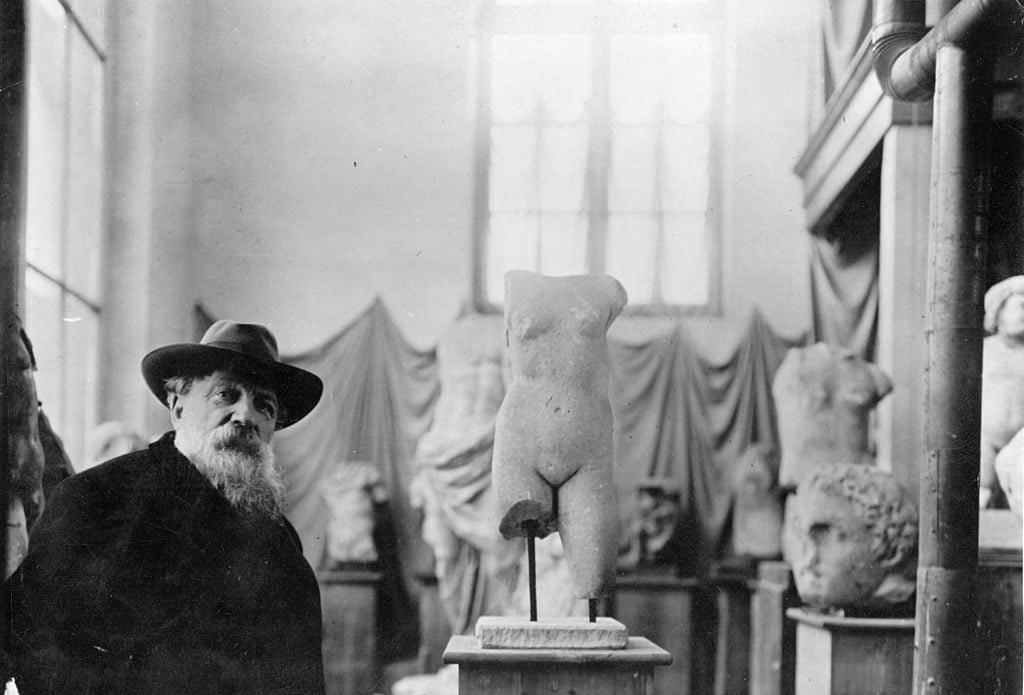

Those who have read Rilke’s Auguste Rodin will sense his religious devotion to the sculptor, who taught him the art of “inseeing” and provided a model of the artist’s life. (Rodin’s mandate: work, always work.) Rodin, too, sensed Rilke’s fidelity to him. Upon reading a French translation of Rilke’s monograph, Rodin immediately hired him as a secretary. Nine months later, the pair parted acrimoniously when Rodin—who is presented as brilliant, egomaniacal, magnetic, and aloof—flew into a rage over a harmless letter.

Corbett, an editor at Modern Painters, arranges the artists in a biographical dance, one that carefully traces their steps together and apart. We begin in Rodin’s cosmopolitan Paris, in 1840, the same year, Corbett notes, that Zola and Monet were born. The nearsighted youth, living in the city of Baudelaire and Haussmann, was a poor student who came late to sculpture. But after he met Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran, the teacher who corrected his vision, Rodin’s obsession began to flourish.

At the Petite École, Corbett writes, Rodin “finished lessons so quickly that the teachers eventually ran out of assignments. He did not care to socialize with his classmates; he wanted only to work.” Corbett lends an air of inevitability to Rodin’s talent, one that was noted by his legion of admiring artists, writers, and lovers. His rise was a matter of time, even if he was ignored by academic art institutions early in life. It was all a question transmission—another of Corbett’s themes. Lecoq simply turned on the faucet by giving Rodin the paradigm of the committed artist.

Rilke’s path was more circuitous. Born to a liberal family in Prague when Rodin was 35, the young Rilke was dressed as a girl by his mother and called “Sophie.” (His given name was actually René.) When he came of age, his parents sent him to a military academy in hopes that he might achieve the officer’s rank that eluded his father, but the students there saw him as “fragile, precocious and a moral scold”—qualities that linger with him throughout the book, until he emerges from Rodin’s shadow as a major writer.

The Trocadero seen through the base of the Eiffel Tower during the Paris exhibition of 1900. (Photo by London Stereoscopic Company/Getty Images)

Much of Rilke’s youth, Corbett demonstrates with layers of anecdote, was spent in search of a master. The first of these was Lou Andreas-Salomé, the philosopher and muse that Friedrich Nietzsche called “by far the smartest person I ever knew.” In 1899, the married Andreas-Salome, for whom Rilke felt a “reckless passion,” took the feeble young poet to meet Tolstoy. The meeting did not go well.

Corbett’s chapters alternate between poet and sculptor until the pair converge, when the ambitious yet unremarkable Rilke, again in search of a master, travels to Paris to write his monograph on Rodin. Even at this early stage, he was one of many Rodin’s true believers. Another was Clara Westhoff, the sculptor whom Rilke would later marry and repeatedly abandon on his vocational wanderings around Europe. It’s one of the many virtues of Corbett’s book that the women in the story are given their due; many, like Westhoff, were talented artists in their own right.

But nearly everyone was infatuated with Rodin, whose tireless labor and genuine artistic newness, combined with his factory-like output, made him the darling of writers and artists in broader Europe, even as his sculptures occasionally scandalized conservative taste in Paris. Corbett’s treatment of this intellectual scene is impressive. There are cameos from Jakob Wassermann (whose lone work published in English is arguably the most horrifying book ever written about marriage), the sociologist Georg Simmel, Sigmund Freud, H.G. Wells, and many others.

Poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) with his wife, sculptress Clara Westhoff, circa 1910. Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Corbett carefully draws out the relationships between these figures, who were all reckoning, in different ways, with the pressures of an emerging mass culture on the lives of individuals. And few of these artists and thinkers were as staunchly individualist as Rodin and Rilke. Their kinship, for better and worse, relied on a shared belief about the vocation of the artist—that it was supreme: no relationship, duty, or family obligation should get in the way of his work.

The question of how much great artists should care—about one another, family, art—is, of course, a matter of empathy. Corbett goes to great lengths to show that empathy was an invention of the 19th century. And it seems at times that Rodin and Rilke struggled with the practice of empathy, as if—like their own art—it was a genuinely new and difficult thing to comprehend.

Related: Sotheby’s $144 Million Impressionist and Modern Sale Sputters

Yet the self-centeredness of Rodin and Rilke, alongside their obsession with artistic transmission between masters and pupils (hence Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet), also happened to generate lasting art. Corbett’s analysis reaches its fruition in a stunning passage on “The Archaic Torso of Apollo,” one that brings together her talent for reading both visual and poetic forms. Her observations unite the two masters aesthetically (as well as historically). “One can almost hear Rodin’s voice speaking through the stone,” she writes, “like the oracle to which Rilke had once asked the almighty question, ‘How should I live?’”

The book concludes at a moment when the historical avant-garde is beginning to rebel against the attitude of Rodin and Rilke. The mass, in a way, swarms the individual; yet the questions remain the same. “How should an artist live?” Corbett’s penetrating story does not—as Rilke or Rodin would have—offer instruction. She relies instead on the rich examples that emerge when an artist’s life is examined with great care. Felt in this way, Rilke’s injunction—to change your life—can seem as heavy or as light as the wind.