Archaeology & History

Archaeologists Discover Ancient Roman Baths Beneath a Museum in Croatia

The pool, mosaic floors and underfloor heating once formed part of Emperor Diocletian’s palace.

The pool, mosaic floors and underfloor heating once formed part of Emperor Diocletian’s palace.

Verity Babbs

Archaeologists working to install a lift and restore the ground floor of Split City Museum got more than they bargained for when they unearthed sizeable Roman baths underneath the building’s reception. The museum in Croatia’s second largest city was founded in 1946 and is held inside the Dominik Papalić palace—the former home of the affluent Papalić family who settled in Split during the 14th century.

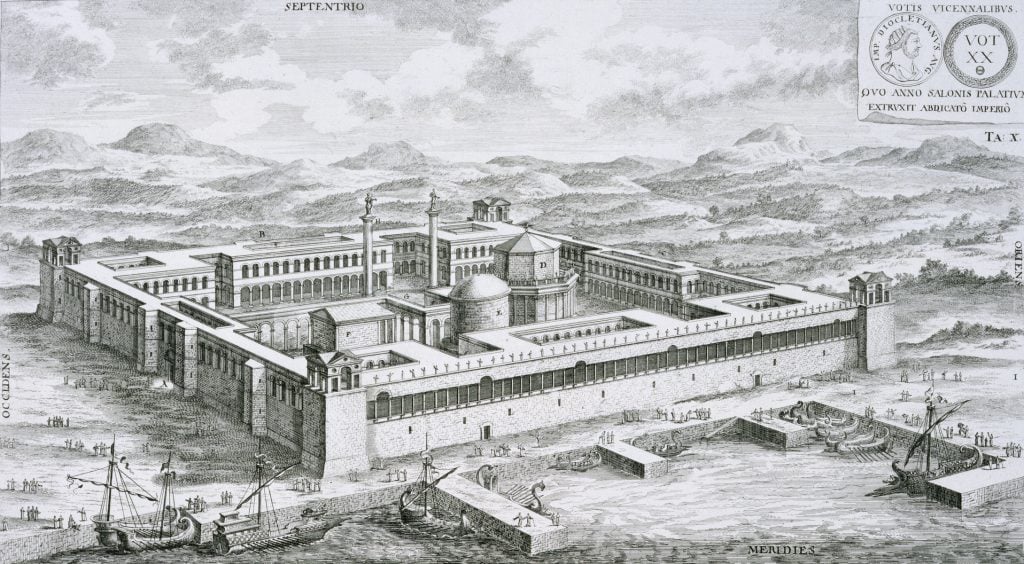

The baths are in a well-preserved condition and include a pool, mosaic floors, ancient underfloor heating, an oil and grape press, and a furnace. Communal bathing was common across the Roman Empire, and baths acted as a space for relaxation and socialising.

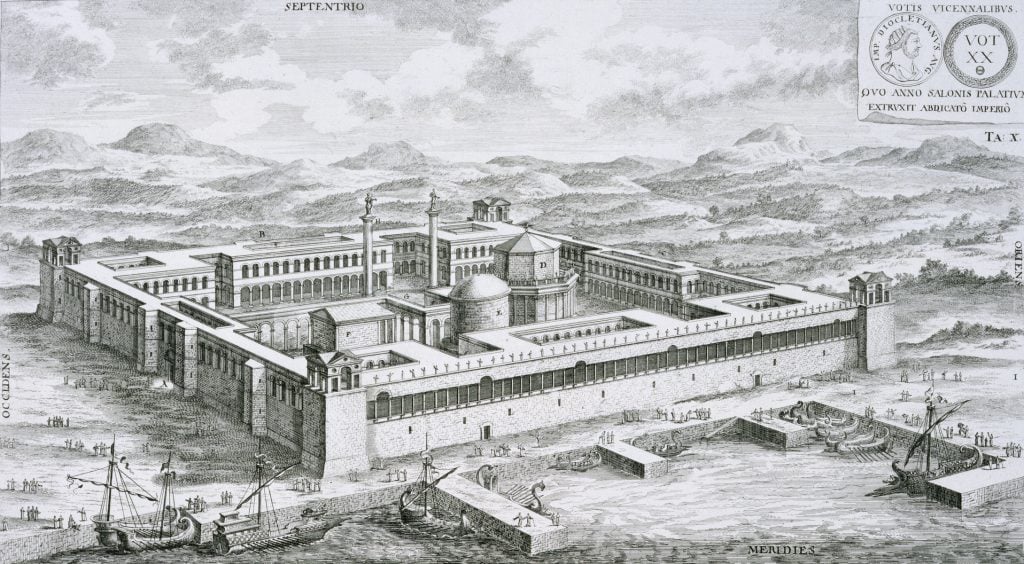

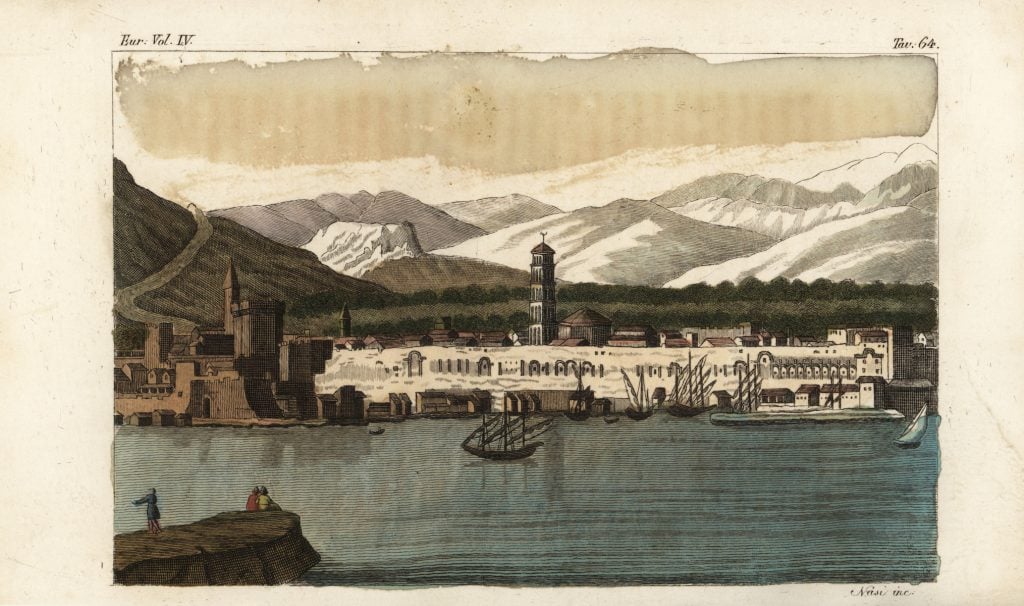

The Split baths are believed to have been part of Diocletian’s Palace, built in the city at the end of the 3rd century for the Roman emperor’s retirement. The large fortress once spanned half of Split’s Old Town, and parts of the palace’s remains are listed UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The discovery of these Roman baths confute historians’ previous understandings about the layout of the ancient complex.

Photo by Michael Nicholson / Corbis via Getty Images.

The repairs were planned as part of the “Palace of Life, City of Change” project, which is described as an “integrated program of development of the visitor infrastructure of the Old City Core with Diocletian’s palace.”

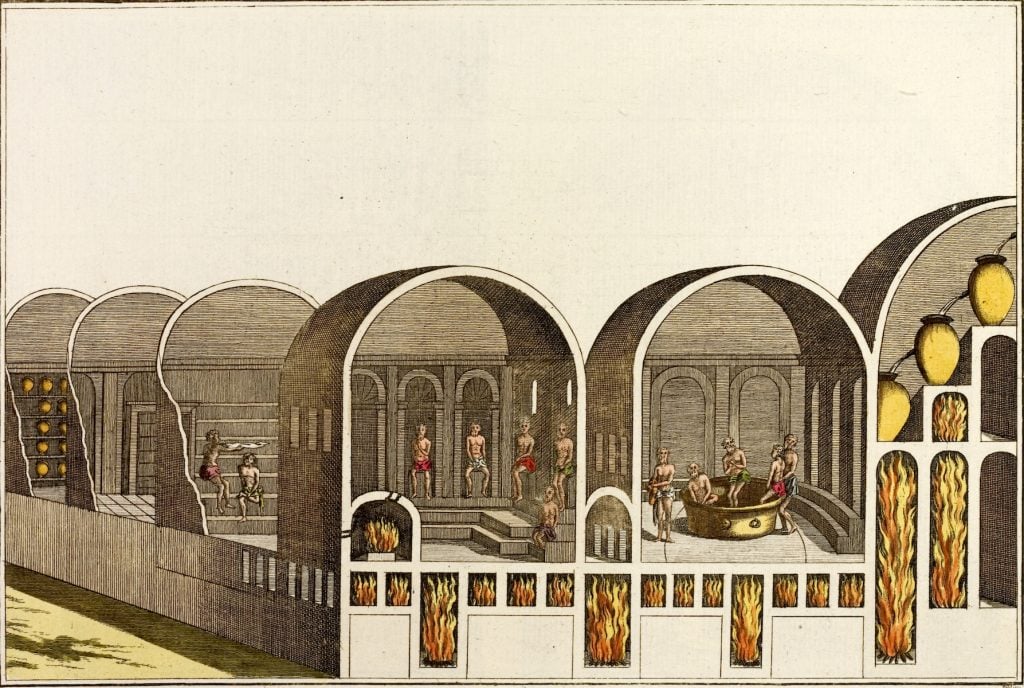

Split lies on the Adriatic Sea coast and was founded in the 3rd century B.C.E. as a Greek colony (then known as Aspálathos). Split’s landscape is made up of myriad architectural styles spanning hundreds of years, from classical ruins to Venetian Gothic structures. The director of the Split City Museum Vesna Bulić Baketić, spoke about the city’s rich architectural composition, “the fact that all of these layers of earlier buildings that once made up the city are visible inside the Split City Museum provides this museum with additional value that is exceptionally rare.”

Giulio Ferrario, Diocletian’s Palace (1842). Photo via Getty Images.

The museum plans to open up part of the newly discovered baths to the public, once the structural integrity of the building has been ensured. The ground floor will also be restructured to celebrate the new discovery. “Showing our visitors the ‘living past’ that speaks to us through the original layers of centuries long gone adds insurmountable value and legacy to future generations,” Baketić said. “It is up to us to carry this out in the best and most professional way.”

More Trending Stories:

Inspector Schachter Uncovers Allegations Regarding the Latest Art World Scandal—And It’s a Doozy

Archaeologists Call Foul on the Purported Discovery of a 27,000-Year-Old Pyramid

A Polish Grandma Found a Rare Prehistoric Artifact—And Kept It Quiet for 50 Years

Art Critic Jerry Saltz Gets Into an Online Skirmish With A.I. Superstar Refik Anadol

Your Go-To Guide to All the Fairs You Can’t Miss During Miami Art Week 2023

The Old Masters of Comedy: See the Hidden Jokes in 5 Dutch Artworks

David Hockney Lights Up London’s Battersea Power Station With Animated Christmas Trees