Archaeology & History

A Spanish Farmer Long Believed a Roman Forum Once Stood on His Land. He’s Now Proven Right

Researchers have identified the Roman ruins in Ubrique as a large venue for public gathering.

In the late 1700s, Juan Vegazo, a farmer and amateur historian in Ubrique, in the southern Spanish province of Cadiz, had a grand theory: buried within the rock and dirt of a nearby hill lay the remains of an ancient Roman forum.

News from the excavations at Pompeii was reviving interest in Roman culture across Europe and inspired Vegazo to buy up the limestone hills and begin excavating. He uncovered inscriptions related to second century emperors, a name for the city, Ocuri, and laid the foundations for future archaeologists to uncover defensive walls, baths, and a mausoleum.

Still, Vegazo’s vision of the past remained incomplete. Until now. More than 300 years on, Vegazo has been vindicated by a team of archaeologists from the University of Granada. In coordination with the town of Ubrique, researchers have uncovered architectural elements in Ocuri that point to a large, public forum that would have served as place of gathering, socializing, and speechmaking. The finding infers that Ocuri was larger and more significant than previously believed.

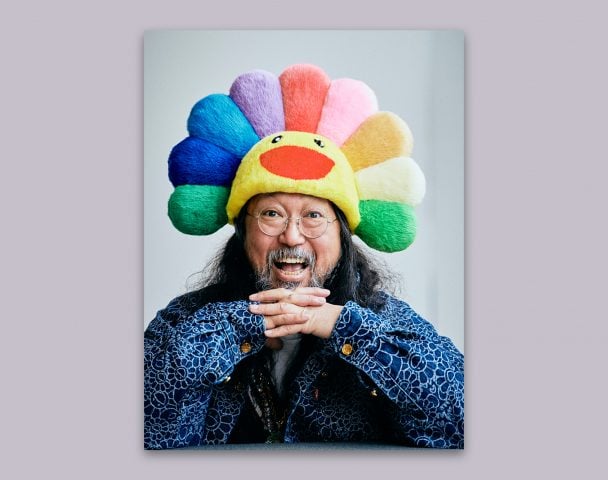

The archaeological site in Ubrique. Photo courtesy of University of Granada.

Key to the discovery is a 50-foot-long wall that is believed to have enclosed the Roman forum as well as architectural elements of large and public buildings. Among these buildings is a large ceremonial site, as offered by the discovery of a monumental altar, column shafts and bases, and statue pedestals. Researchers believe the site supported religious practices related to water that mixed Roman and local customs.

“The excavations outline a space that is crucial for understanding the arrival and consolidation of the Romans in the southern Iberian Peninsula, as well as their hybridization with the communities that had already settled in the area,” the University of Granada’s Department of Prehistory and Archaeology said in a statement.

Roman archaeological ruins in Ubrique, Cadiz. Photo: Cristina Candel / Cover / Getty Images.

With its strategic hilltop position, it’s long been believed that a settlement pre-dated the Romans with researchers suggesting the absorption was both physical and cultural. Researchers now believe the site was inhabited until the end of the 4th century C.E. based on coins that were discovered—in particular, one marked with a Christogram, which is among the earliest forms of Christian iconography and was deployed by Constantine I in 312 C.E.

This continued presence in the southern reaches of Hispania, as the territory was known following its annexation in 19 C.E., was partly due to the trade advantages it offered, as it connected the coast to the interior parts of the province. Along with showing Ocuri’s size, the discovery of North African goods, including ceramics, suggests a strong and enduring (through the late 3rd century at least) economic links across the peninsula.

Aside from Roman discoveries, researchers also found evidence of medieval defensive structures.