Art World

Geta Brătescu, Whose Playful Art Defied Romania’s Repressive Regime, Has Died at 92

The artist only rose to international attention in her later years.

The artist only rose to international attention in her later years.

Sarah Cascone

Geta Brătescu, a Romanian artist who achieved international acclaim in recent years, including at the 2017 Venice Biennale, has died. She was 92.

The artist’s career spanned seven decades, and Brătescu was working daily in the studio into her final months. In 2017, Brătescu showed work in documenta 14 and in the Romanian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Titled “Apparitions,” the show marked the first time Romania dedicated its pavilion to a female artist.

“That Geta lived to see her art embraced so enthusiastically on the international level at the 2017 Venice Biennale and at her first New York solo exhibition at our gallery last year means so much,” said Hauser & Wirth president Iwan Wirth in a statement. Brătescu was “a true artist who even in the darkest times maintained her sense of playfulness and freedom. Her powerful life force went in so many directions, from drawing and graphics and photography, to animated videos and tapestry, that even in her 90s she embodied the spirit and passion of a young person.”

The gallery began representing Brătescu in April 2017, and has since held exhibitions of her work in New York and LA. She is also represented by Ivan Gallery in Bucharest, where she lived and worked.

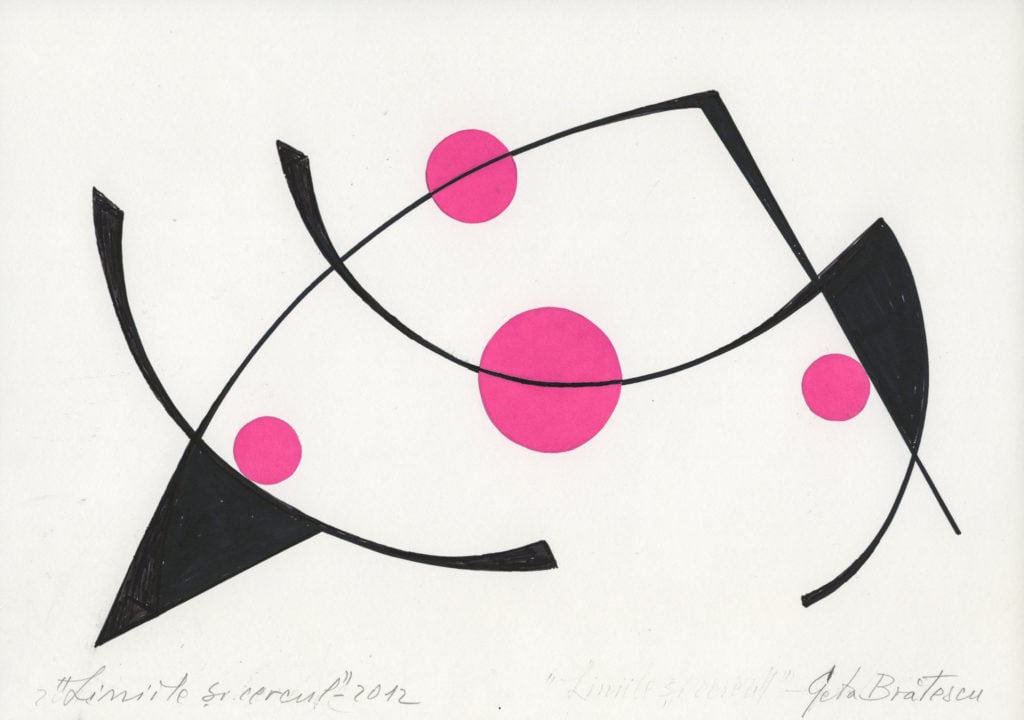

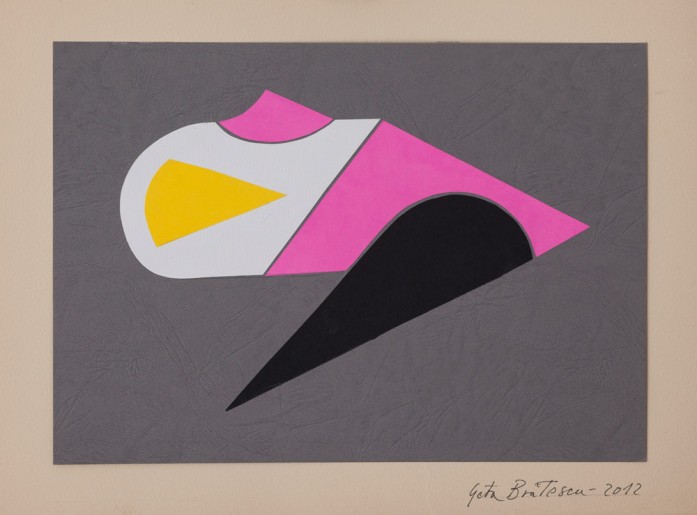

Geta Brătescu, The Lines and the Circle (2012). Photo by Stefan Sava, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

Brătescu was born in Ploiești, Romania, in 1926. She went on to study at the Bucharest School of Belle Arte in 1945, but, four years later, the new Communist government kicked her out of the program. She began working as an illustrator and magazine artistic director, and sometimes collaborated with her husband, photographer and engineer Mihai Brătescu, whom she married in 1951.

For the next 40 years, under the oppressive regimes of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej and Nicolae Ceausescu, Brătescu found ways to work outside the government-mandated art of social realism.

“During communism it was almost mandatory to make political art, so the avant-garde had to be political in an unpolitical way,” art historian Sebestyen Gyorgy Szekely told the New York Times earlier this year. “One of Geta Bratescu’s escape routes to make unpolitical art was to use mythology, and the other way she did it was in her handling of the process of art, using the act of drawing as a way to discover the world.”

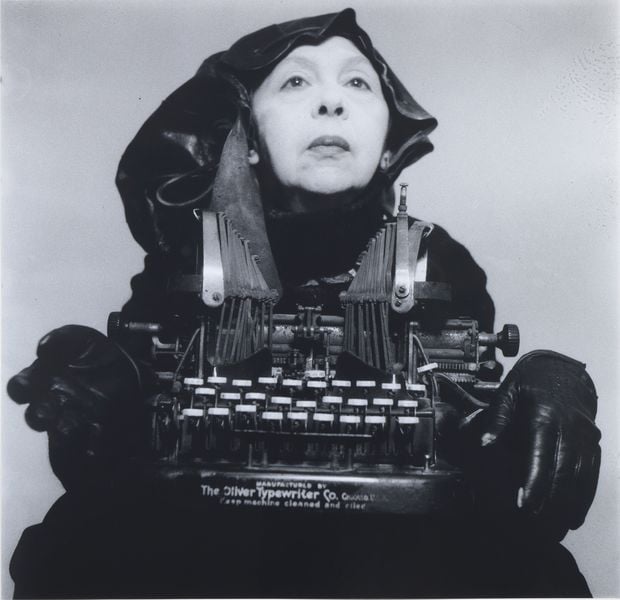

Geta Brătescu. Photo by Cătălin Georgescu, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth and Ivan Gallery.

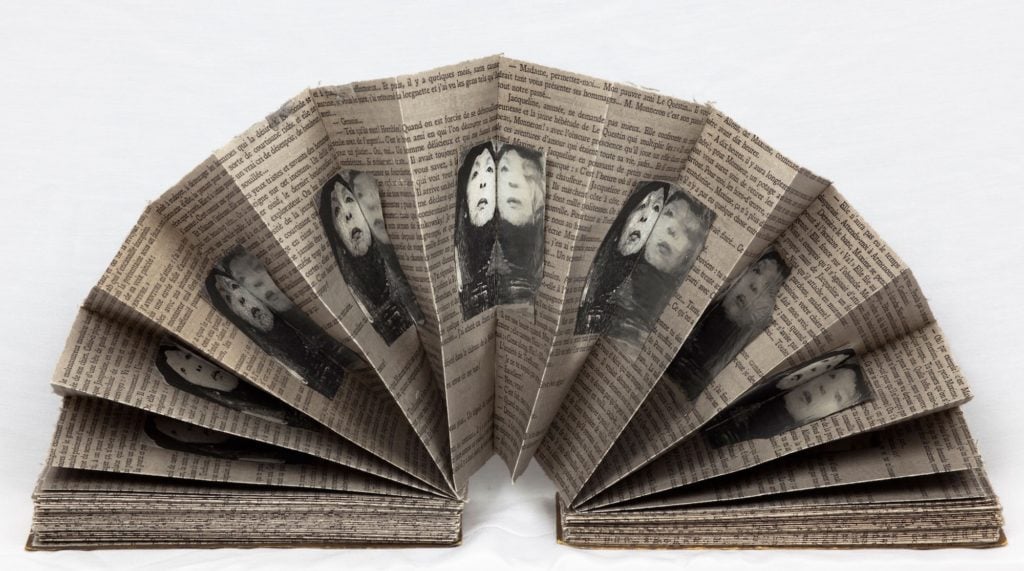

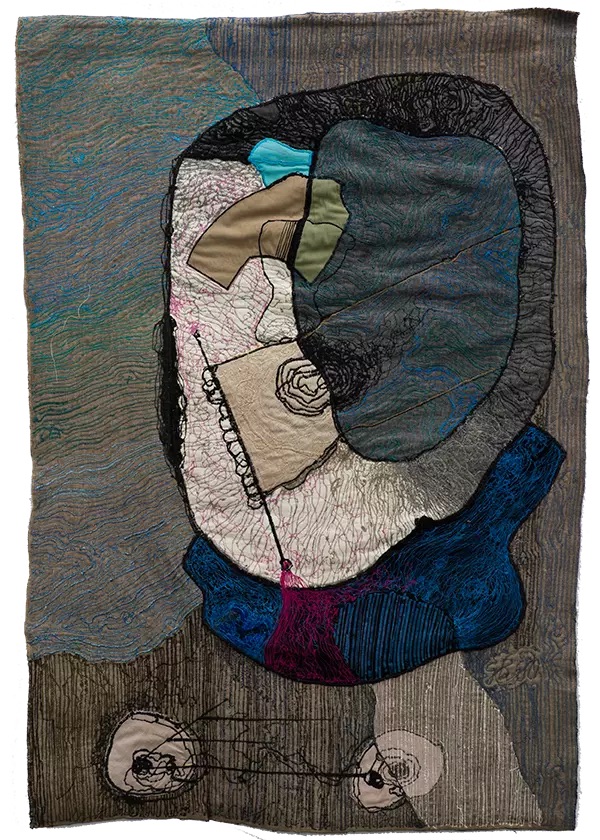

Brătescu embraced a wide range of mediums in her practice, including drawing, textile collage, video, animation, installation, photography, and graphic design. She was often inspired by literature, including the writings of Samuel Beckett, Greek mythology, and the female characters in the legend of Faust.

Gender-based themes figure prominently in Brătescu’s work, yet she described her imagery as feminine, not feminist. “Feminism is a uniform,” she said in a 2013 book on the artist. “Femininity is a specific energy—it is an aura, a light that is a gift… which enriches the world.”

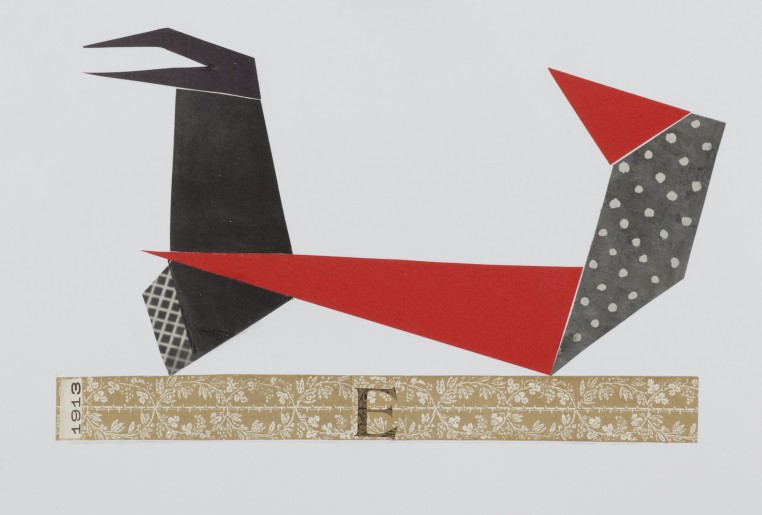

Geta Brătescu, detail of Aesop (1967). Photo by Stefan Sava, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

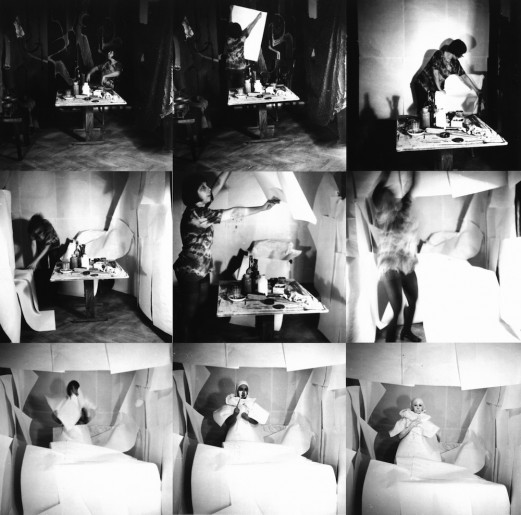

Brătescu’s best-known work is perhaps Atelierul (The Studio) (1978), an experimental black-and-white film that shows the artist waking up in her studio and drawing all over its surfaces and rearranging the objects in the room.

Brătescu only came to international prominence in recent years. She was the subject of museum shows at Tate Liverpool in 2015, the Hamburger Kunsthalle in 2016, and London’s Camden Arts Centre in 2017.

“Her works, her writings and her studio are her artistic legacy,” said Ivan Gallery founder Marian Ivan, who first began working with Brătescu in 2007, in a statement. “This is something that will endure and will continue to exist and go on in the future.”

See more works by the artist below.

Geta Brătescu, detail of Magnetii in Oras (Magnets in the City) (1974). Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

Geta Brătescu, L’aventure. Roman Inedit (The Adventure) (1991). Collection of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest. Photo by Stefan Sava.

Geta Brătescu, Towards White (Self-Portrait in Seven Sequences) (1975).

Geta Brătescu, Medea’s 10 Hypostases’ (1980). Photo by Stefan Sava.

Geta Brătescu, Game of Forms (2012). Courtesy of Ivan Gallery.

Geta Brătescu, Doamna Oliver în costum de călătorie (Lady Oliver in her travelling costume) (1980). Photo by Mihai Brătescu, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth.

Geta Brătescu, Le Theatre des Formes (2011). Courtesy of Ivan Gallery.