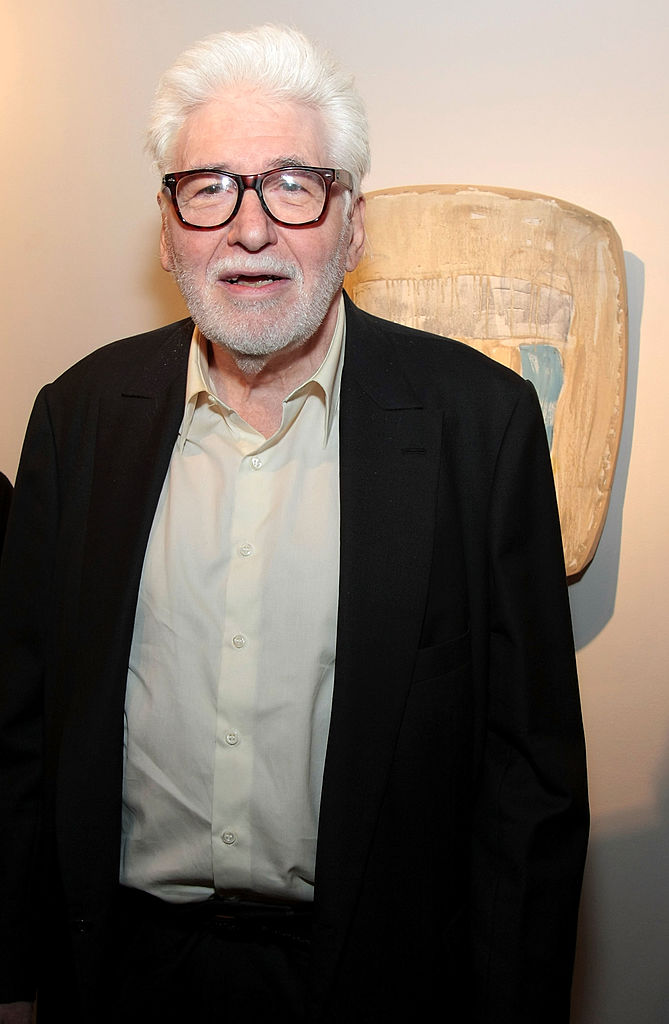

Artist Ron Gorchov, whose idiosyncratic paintings found admirers in the 1970s, but who fell out of favor for almost two decades before eager new audiences flocked to his work in the 2000s, died on Tuesday in New York. He was 90.

The artist, best known for his biomorphic abstractions, which he painted on casually assembled shield-shaped canvases, was an early critic of the idea that painting was dead, as many of the artists of his generation believed.

Alongside artists including Richard Tuttle and Blinky Palermo, Gorchov made a smaller claim: that painting could go on if artists gave up their Modernist attempts at grand gestures, and focused instead on making smaller, quieter, more personal expressions.

Gorchov was born in Chicago in 1930. At 14 years old, he began taking classes—alongside older students who were benefiting from the GI Bill—at the Art Institute of Chicago.

He briefly attended the University of Mississippi, where he said he once fished with novelist William Faulkner, before returning to his hometown and finishing his studies. In 1953, along with his son, Michael, and his wife, Joy, he moved to New York in search of new opportunities.

An installation view of a show by Ron Gorchov at Nicholas Robinson Gallery in New York. Photo by Will Ragozzino/Getty Images for Nicholas Robinson Gallery.

In an apartment on 8th Street, across the street from the former home of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Gorchov raised his family and painted at night while working as a lifeguard, initially at Coney Island.

“But somehow we had time for everything,” he recalled in a 2006 interview with the Brooklyn Rail. “We had parties with friends. Took Michael everywhere. Joy had a piano and singing coaches and studied acting. I could see all the shows in one afternoon, after midnight talk to artists in bars, then paint all night and sleep three hours in the morning. It was exciting and we didn’t want to miss out on anything.”

In 1960, he landed his first solo show at Tibor de Nagy gallery, which caught the attention of critic Dore Ashton. In her generally favorable New York Times review, she expressed hope that Gorchov’s talent would not be “drowned in the brouhaha” of chatter that accompanied the feverish search for new talent.

Around 1966, Gorchov narrowed his focus to his shield- (and saddle-) shaped works, which gave him a set form to work within. “I also discovered that, with the new structure, it creates an even tension throughout the whole surface,” he later said. And in the years that followed, interest in his work grew.

After a handful of solo shows in the ’60s, he was included in “Rooms,” the now famous group exhibition that inaugurated PS 1 Contemporary Art Center, which was founded by Alanna Heiss in 1976. Nearly 30 years later, the institution returned to Gorchov with a solo exhibition including never-before-seen works.

Ron Gorchov, installation view. Courtesy of Cheim & Read.

The show had its detractors. Critic Ken Johnson wondered aloud whether the artist had “overly limited his formal possibilities,” adding: “Even in a show as economical as this, the saddle-shaped paintings become too repetitive.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, which were quieter decades for Gorchov, there seemed to be a similar feeling in the air. “Nothing worked well for me in the ’80s,” he once said. “The ’90s passed quickly.”

And although he had nearly a dozen shows between 1990 and 2000, he only presented works in group shows for the 10 years between 1995 and 2005, when dealer Vito Schnabel picked him up and helped revive his career. “They understand that artists probably like to be able to work and also live well,” Gorchov later said of Vito and his father, the painter Julian Schnabel. In 2012, Gorchov joined the stable of Cheim & Read, which has since hosted three solo exhibitions of his work and published two catalogues.

By then, interest in painting was on the rise and a sense of pluralistic openness to all media settled over the art world, and a younger generation of artists, including Josh Smith and Wade Guyton, took up the mantle of abstraction.

Gorchov, who never tired of painting, felt that the art form would always have a future. “Even though it was always made for a small audience, I believe that painting will be looked at,” he told the Brooklyn Rail. “It’s lasted 40,000 years, why not another 40,000 years?”