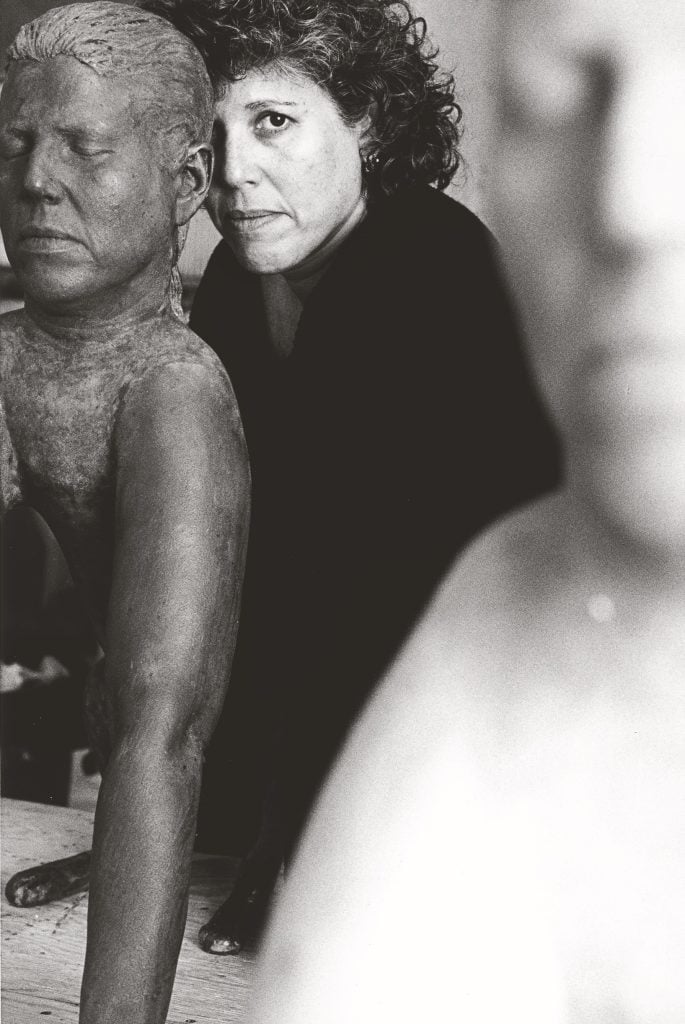

Some weeks after I started conducting interviews for this profile of the sculptor Rona Pondick on the occasion of her new show at Marc Straus in New York, after I’d talked with her friends, dealers, collectors, confidants, and twice to her husband, the painter Robert Feintuch, Pondick sent me an email to confirm our next interview. She added: “When I got home yesterday, Robert shared with me what you talked about.” It was largely about Pondick’s childhood. “Must say it is a little weird knowing I am being examined so closely. I am feeling things I didn’t expect.”

It’s true I had been nosy, probably because Pondick, as far as I could tell, has always seemed so guarded. Her published interviews are master classes in precision. You can almost see her marking up texts to clarify the finest of details. She leaves a lot out. She avoids discussing life outside the studio. Family talk is muted. Her medical history, long an open secret, and by all accounts an indispensable avenue into her sculpture, is relegated to footnotes. Every one of my interviewees described her as exacting or blunt or pertinacious, none more diplomatically than Thaddaeus Ropac, her dealer of more than 30 years: “She has developed something very much her own, unimpressed by trends.”

“Or by the market,” he added, perhaps a bit wistfully.

So I understood why Pondick was apprehensive about my probing. I was apprehensive too. Pondick has a powerful personal presence. She speaks at times in a clipped manner, and her steely gray hair, chiseled features, and handsome, starkly shaped eyeglasses suggest sternness. “She doesn’t suffer fools lightly,” Steven Zevitas, one of her gallerists, told me. He admitted that his very first impression upon meeting her was intimidation. “She has this way, when she first meets you, of giving a stare, and you feel like you’re being sized up. It’s like she’s seeing into you.”

Her sculptures did nothing to assuage my anxiety. The first time I saw one was at the Yale University Art Gallery, where Fox (1998–99) robbed me of my calm. As I turned a corner in the museum on a visit one day, the sculpture practically snapped at me, and it was a grisly sight, this human head—cast from Pondick’s—grafted onto a canine body. What bothered me most was that I laughed. I didn’t like being seduced by a monster.

Later, when I saw landmark earlier works like Little Bathers (1990–91) and Mouth (1992–93), I understood that my initial impression was spot on: I was in the presence of real perversion. It was hard to look away. Mouth in particular was riveting to me. Cast from the artist’s palate into 600 sets of dirtied, gnashing teeth, covered all over in hair—or maybe fleas?—and scattered across the floor, the filth seemed to get everywhere.

“People have strong, visceral responses to her work,” Feintuch told me. “It’s not always comfortable.”

A detail from Rona Pondick’s 600-part installation, Mouth (1992–93). The work is made mostly of rubber casts taken from the artist’s mouth and covered over in flax. It’s part of the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg/Seoul. © Rona Pondick.

A Freudian Walks Into a Bar

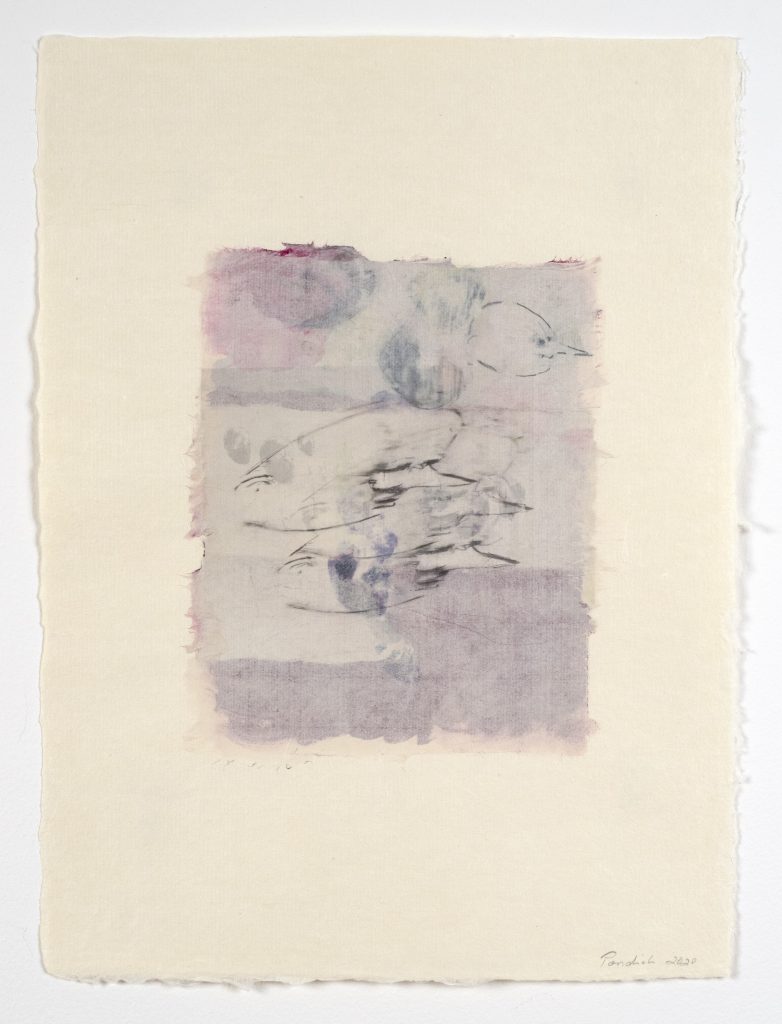

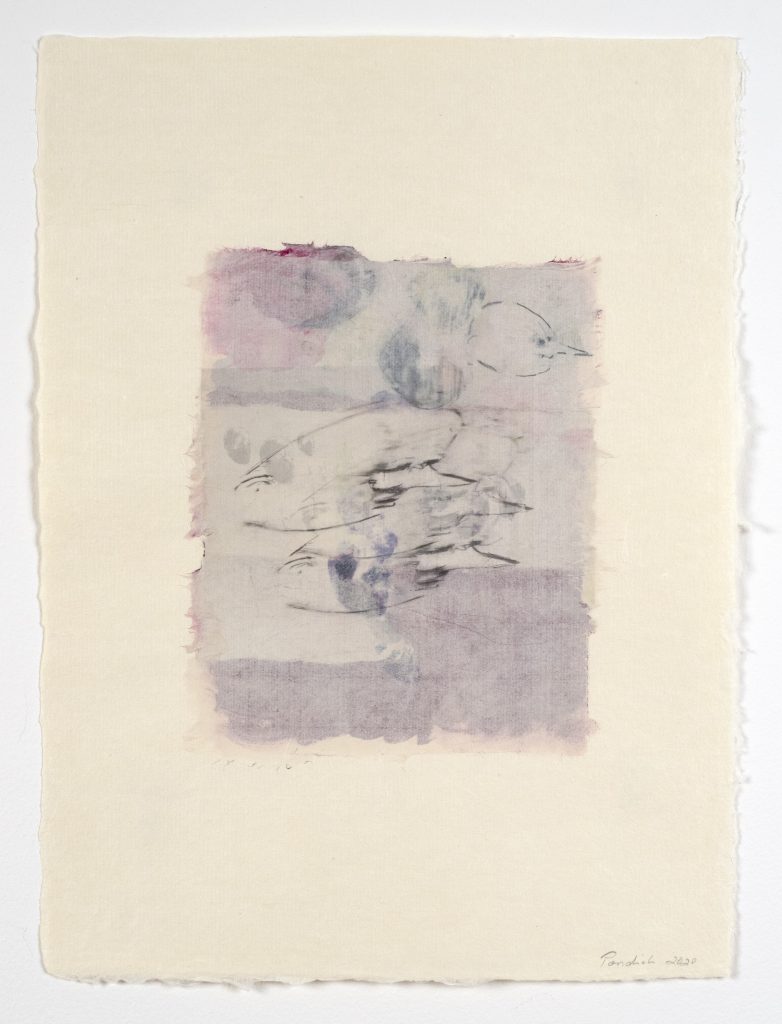

Pondick’s newest works are permeated with the same sense of disquiet she has sustained throughout her 35-year career. Outside conditions—the pandemic, police brutality, gun violence, desperate inequality, the collapsing environment, a resurgent right wing, the dissolving old order with nothing to replace it, and, suddenly, war in Europe—have framed her focus. When the coronavirus shuttered New York in March 2020, Pondick retreated from her pristine laboratory studio in Alphabet City to her home on Cooper Square, where she has lived with Feintuch since 1977. In her radically truncated atelier, she scaled down and began making drawings like Small Heads #45 (2020), on view at Marc Straus.

Pondick, who has only shown her drawings a handful of times, has six on view at Marc Straus. This work is titled Small Heads #45 (2020). Photo: Marc Straus, New York. © Rona Pondick.

“I normally draw when I’m lost,” Pondick told me. “I don’t think, if the virus had not happened, I would have been doing these. But I was in a very fertile place. I got very turned on by the materiality of the paper, which is like a skin, practically. It’s so thin. People don’t realize when they are framed, but they’re looking at layers of drawings. All these ghosts come through. I don’t know if it was because of the virus, but I am about to turn 70 this year. How many more sculptures will I make? What does it mean, at this point in my life, to be making more? And I started seeing that the ghosts in the drawings started showing up in the sculptures.”

What changed from one medium to the next was rendering: The figures in the drawings, with their sharp, evil noses, are pulverized into paper. In the sculptures, the heads come alive in great naturalistic detail, especially at reduced, intimate scale. (For most of the past 25 years, Pondick has created large, heroically sized work. The new sculptures at Marc Straus sit on pedestals.)

A detail from Small Heads #45 (2020), showing Pondick’s pulverizing technique. Photo: Marc Straus, New York. © Rona Pondick.

The sculpted heads, all created from the lifecast Pondick made for Dog (1998–99), her first-ever sculptural self-portrait, pulsate with the kind of energy only a remarkably sensitive craftsperson can realize. This point is important: Pondick is not a conceptual artist. She has repeatedly told interviewers that she thinks “with my hands.” Exactly what makes new sculptures like Small Yellow Red Orange Yellow (2019–21) so unsettling is the thought of Pondick massaging two small, demented animal bodies into being and then adding, like cherries on top, Lilliputian models of her own head.

For most of her career, Pondick worked with muted colors. That changed in 2013 when she began experimenting with pigmented resin and acrylic. The work above, Small Red Yellow Yellow Green (2014–18), is one of the latest results. Photo: Marc Straus, New York. © Rona Pondick.

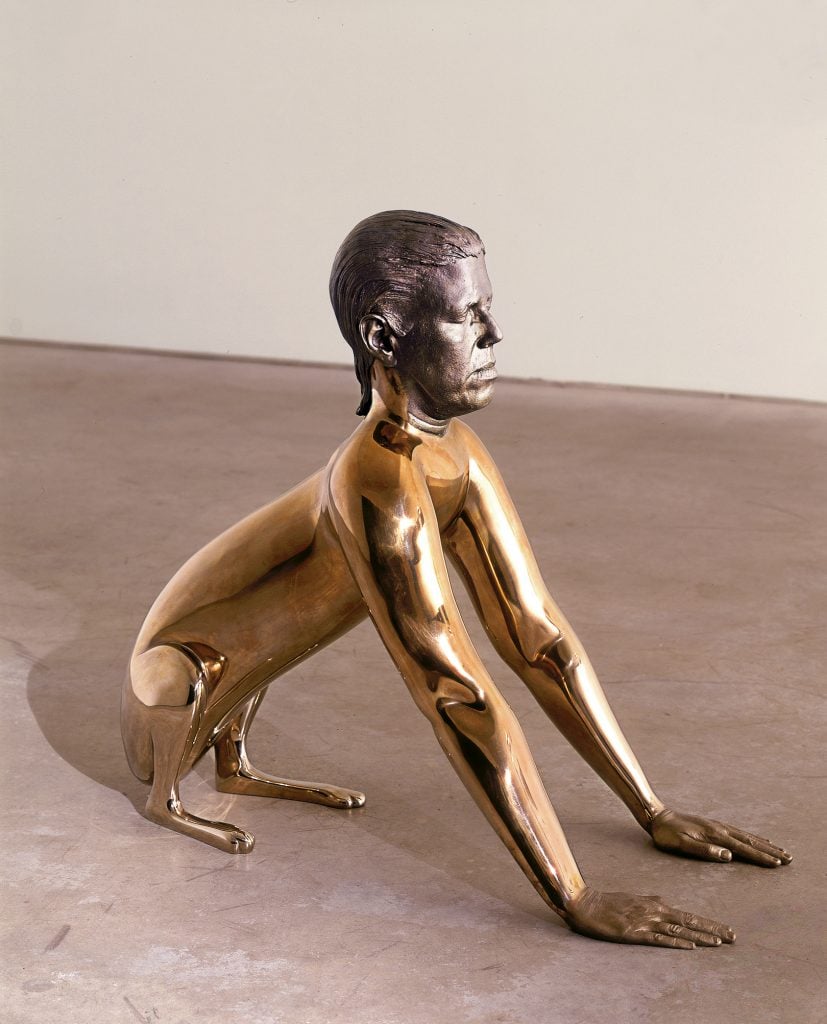

The titles of Pondick’s works say everything about her reticence. She is a Modernist (and a latter-day Minimalist) not only in her material specificity, but also in her linguistic reservation. She prefers to talk about how something was made, rather than why. Ask her about Monkeys (1998–2001)—maybe her most important sculpture, and a Bernini-like display of violent virtuosity, in which a mob of apes, some with human heads and arms, all cast from Pondick’s body, crawl up and over one another to enact some travesty—and she’ll explain that it took so many years to complete because she was relying on nascent 3D-scanning and printing technology that could barely accommodate her ambitions.

“The software kept crashing,” she told me. “It was so immature, this scanning technology in 1998, that what was supposed to take a few weeks took a year.” Printing was its own ordeal.

Pondick spent four years crafting and refining Monkeys between 1998 and 2001. This specific example (the work comes in an edition of six) is owned by the New Orleans Museum of Art. Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg/Seoul. © Rona Pondick.

Yet it’s the sexual implications and base brutality of Monkeys that keep drawing me back; it’s impossible to resist psychoanalyzing the work for fuller meaning beneath material reality. I’m not the first to be mesmerized. The critic Michael Brenson once called Pondick’s sculptures “Freudian vaudeville acts,” and Nancy Princenthal said her work had the “irrefutability of dreams.” Feintuch told me of a child, wheeled into a gallery in a stroller by his mother, who was so drawn to Pondick’s Double Bed (1989), which is covered in ropes and baby bottles, that he tried to crawl out of his seat to suck on the nipples.

“I think Rona’s work often works that way,” Feintuch told me. “People have physical responses that are emotional.”

Robert Feintuch, Pondick’s husband, tells the story of a small child who tried to crawl out of his stroller to suck on the nipples on Pondick’s Double Bed (1989). Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg/Seoul. © Rona Pondick

The Origin Story

Pondick was born in Brooklyn, New York, on April 18, 1952, and grew up in East Flatbush in a two-family house with her mother and brother. Her grandparents on her mother’s side, Jewish refugees from the October Revolution, lived downstairs. “My grandfather nurtured my interest in drawing and painting, so when other kids were getting normal toys, I was getting paint kits,” Pondick said.

Her relationship with her mother—whom she has often credited, along with Kafka, as one of her chief influences, without ever elaborating—was fraught. “She was a very damaged, troubled human being,” Pondick said. “She was horribly physically and emotionally abusive. That abuse, in a weird way, impacted my work. It fed me in a way. She was a nightmare for me to survive. But out of something awful, something good came.”

Pondick attended Queens College as an undergraduate and the Yale School of Art for her master’s degree, which she finished in 1977. Later that year, she and Feintuch, whom she met at Yale, moved to Manhattan and made a living painting houses.

Lead Bed (1987–88), an early work of Pondick’s, is one of several crafted to look like beds. Her 1988 show at the Sculpture Center was organized largely around the theme. Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg/Seoul © Rona Pondick

Her first solo shows came in 1988, when art dealer José Freire and the Sculpture Center in New York hosted twin exhibitions. In 1990, she agreed to terms with Thaddaeus Ropac in Salzburg, and 10 years later, with Ileana Sonnabend in New York. By then, she had been included in the Whitney Biennial (1991), the Venice Biennale (1993), and the Lyon Biennale (2000).

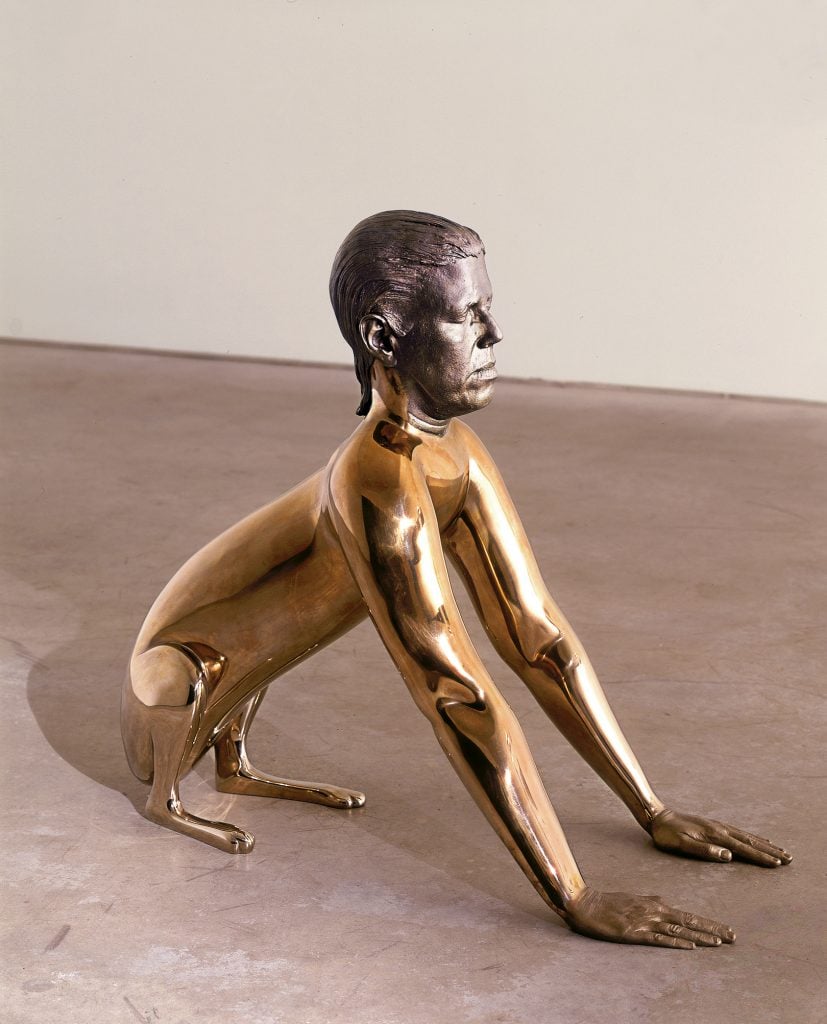

Marc Straus, a collector of Pondick’s work decades before he became her dealer, was instrumental in getting Sonnabend director Antonio Homem on board. “One Saturday morning, I went into Sonnabend, and I told Antonio, ‘We’re going to get in a cab and do a studio visit,’” Straus said. In progress in Pondick’s studio that day was a wax version of Dog, to which Homem was instinctively drawn.

Dog (this version in yellow stainless steel from 1988–2001) was perhaps Pondick’s most generative sculpture, marking the first time she cast her head for her work. One edition (out of six total) is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Another is in the Sonnabend Foundation Collection. Photo: Sonnabend Gallery, New York. © Rona Pondick.

“I thought it was very interesting, very surprising,” Homem told me of the sculpture. “I think it was at that moment that Rona said something about destroying it because it had problems. She wanted to make it in a more solid material. I told her I thought it was completely crazy, that it was a very good work and she shouldn’t do it. Not much later on, she called me and said, ‘You liked it so much, I decided I wanted to give it to you.’”

Dog was Pondick’s most generative artwork. It marked the first appearance of her head in her sculpture; the introduction of hybrid human/non-human forms; and is the origin of her earliest experiments in bronze, aluminum, and stainless steel after years of working with more pliable materials.

Its production was excruciating. To create the model of her head, Pondick had two friends encase her in medical-grade silicone. “That was important to me, because it gives great detail,” she said. “You’re encased for over two hours. Most people put straws in their nose to prevent suffocation. But I didn’t want to disfigure my nostrils in the mold. So I said, ‘No straws. We’re just going to paint around my nostrils.’”

“I’m very lucky I kept a pad and pen on my lap. Because I had no idea that when the rubber went over my neck, which was covered in mesh and then plaster—you’re really encased. It’s real sensory deprivation. I started choking. And I had to write, ‘slit neck choke.’ So they slit the neck. By the end of this, after several hours, I was writing, ‘Get this fucking thing off of me.’ I was really going to lose it. I have treated that one lifecast like gold. I’ve never done another since.”

A Look at the Medical Chart

Because Pondick’s body is embedded into her work; because her sculpture inaugurates physical unease; and because life always makes its way into art, it is impossible to honestly discuss her sculptures without acknowledging her medical history. A brief sketch would begin in 2006.

That year, on a flight home from installing a solo show with Ropac in Salzburg, her right arm went numb. Before long, she couldn’t move her head without feeling she would faint. She ignored the discomfort, assuming it would be temporary. Almost in passing, she told a friend, an orthopedic surgeon, about her symptoms. He urged her to visit a specialist. By the time doctors realized they needed to operate on her spine to remove calcification on a ligament that was effectively strangling her spinal cord, she couldn’t feel anything on the right side of her body. She was advised not to walk around on her own out of fear that a fall would leave her paralyzed.

“It’s hard to hear this,” she told me. “They had to break through my spinal canal, front and back, to get access to the ligament compressing the spinal cord, and remove it with a scalpel. Then they had to put my spine back together.” The procedure required two painstaking surgeries—one for nine hours, with Pondick lying face up; another for 10, with her lying face down—done over the course of four days.

“I’ve got metal reinforcing the front and back of my spine on five levels. That’s part of the reason I have so many neurological issues. I have what’s called permanent spinal cord injury, which means scarring of the spinal cord,” she said. “My neurosurgeon to this day cannot believe I’m back to work and as functional as I am.”

While recovering from her surgeries under the influence of morphine, Pondick began having fever dreams. “I was fantasizing about my head leaving my body and floating into trees and into the clouds, and it gave me the most blissful, warm feeling,” she said. “It gave me unbelievable solace in the intensive care ward.”

One hallucination in particular—of her head nestled inside a cluster of branches, eyes closed in a state of calm acceptance—was so vivid that it became the basis for Head in Tree (2006–08), one of her greatest sculptural achievements.

Head in Tree (2006–08), which Pondick dreamed up when recovering from two intensive spinal surgeries. “I was fantasizing about my head leaving my body and floating into trees and into the clouds,” she said. “And it gave me the most blissful, warm feeling.” Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg/Seoul. © Rona Pondick.

The stainless steel work is an education in delicate, precise handiwork, and a pacific counter-study to a rabid display like Monkeys. Spend enough time with it (even images of it) and the trees you see in everyday life will never look quite the same. (“I can’t look at a tree now without looking at it as a piece of sculpture,” Feintuch told me.) I imagine any viewer seeing it for the first time would immediately connect its cerebral sensibility not only to the head that crowns the work, but also to the spinal column-like tree trunk that cascades to the ground. Yet for years, Pondick declined to illuminate her audiences to the full genesis of the sculpture, and avoided talking about her surgeries in public.

A detail from Rona Pondick’s Head in Tree (2006–08). This image shows the work at the Sonsbeek biennial in Arnhem, the Netherlands, in 2008. Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg/Seoul. © Rona Pondick.

“I didn’t want anyone to know anything happened to me,” she told me. “I didn’t want anyone to think I’d lost any physical functioning. In interviews, people would ask me questions, and I just said, ‘I won’t discuss it.’

“I‘ve gone through a long period where I felt like my history—my emotional history—didn’t need to be talked about. I feel more comfortable letting it go organically into the work,” she said. “When I look back on my work, usually a decade after, I see things very differently than when I was making it. Two decades later, I see it that much more differently. When it gets to three decades, I start to look at it objectively, almost to the point where I’m no longer the maker. So I’m ambivalent about how much to share. What do I really want to share?”

Small Red Yellow Yellow Green (2014–18) is among the pigmented resin and acrylic works on view at Marc Straus. Each head in each sculpture is modeled on Pondick’s own. Photo: Marc Straus, New York © Rona Pondick.

Trauma is a funny thing (and not only literally, as Kafka knew). It lurks forever in the faculties (“the body keeps score,” as the psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk put it) and makes periodic attacks at moments of vulnerability, or creates them. How did we get to be this way? What originating violence did this? Figuring out is a life’s work arranged in fragments around the chores of daily life.

In recent weeks, I had many further conversations with Pondick, most of them practical. She shared contact details for friends and colleagues, and I secured images and checked facts. But there was also the issue of calming her nerves. Over the course of many hours, she had divulged to me details about her life that she’d otherwise kept tidily tucked away for years, and then had time to consider the implications of telling. She didn’t ask once what would end up in the article, but I sensed she was becoming increasingly anxious to know. Like any person, she has a picture of herself to protect.

Every journalist senses a subject’s anxiety, because it seeps into the journalist too. I became attached. I admire Pondick. And Feintuch is a fascinating painter. When they had my wife and I over for dinner, they became the first people anywhere to learn our unborn son’s name. We discussed a potential monograph on her work, and I needed to maintain access. I had no interest in alienating her. Yet there was a distinct possibility—and this is what scared us both—that if I drew the case too definitively between her life and art, I would foreclose her work’s many other possibilities, the ones that could occur to her years after the event. That would be unacceptable to her. It would be the end of the relationship. “I don’t want a didactic explanation of my work,” she told me. “I want it to be experienced fully.”

So do I.

“Rona Pondick” is on view at Marc Straus, 299 Grand Street, New York, March 2–April 16, 2022.

Rona Pondick in her Alphabet City studio. Photo: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London/Paris/Salzburg/Seoul.