Art World

Have You Seen This Artwork? A Famous Dealer’s Family, Desperate for Leads, Is Crowdsourcing Its Search for a Nazi-Looted Degas

A German dealer is refusing to reveal the identity of a Swiss collector who owns the Nazi-looted work.

A German dealer is refusing to reveal the identity of a Swiss collector who owns the Nazi-looted work.

Sarah Cascone

The family of Paul Rosenberg has recovered all but 60 pieces from the Jewish art dealer’s extensive collection, which was stolen by the Nazis during World War II after the family fled France in 1940.

Now, they are on the hunt to recover an 1890 pastel by Edgar Degas, Portrait of Mlle. Gabrielle Diot. It is known to be in Switzerland, and the current owner of the work (whom the family has yet to identify) has tried to discreetly sell it privately, so far refusing to return it to Rosenberg’s heirs, despite a global push to ensure restitution of Nazi-looted artworks.

The Rosenberg family’s efforts have extended across three generations, dating back to the closing days of the war, when Rosenberg’s son, Alexandre, a French lieutenant, stopped a train leaving Paris in August 1944. Among the cargo was a sizable part of Rosenberg’s collection.

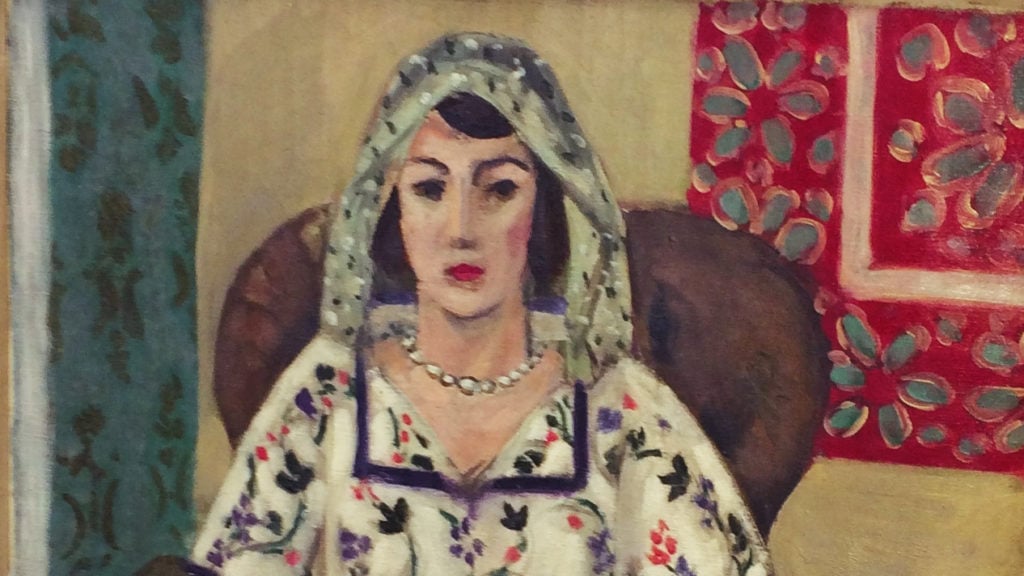

Other works have turned up far more recently, such as Henri Matisse’s Woman Seated in an Armchair, returned amid much drama after it was discovered in November 2013 among the hundreds of artworks, some of tainted provenance, stashed away in Cornelius Gurlitt’s Munich apartment.

Detail from Henri Matisse’s Seated Woman/Woman Sitting in Armchair (1921), part of the Cornelius Gurlitt hoard. Courtesy of Lost Art Koordinierungsstelle.

Despite the considerable progress made by the family over the years, the process has not been easy. “It has been completely frustrating,” the dealer’s granddaughter, Marianne Rosenberg, who works at a New York gallery, told the New York Times. “Something appears, then it disappears again and you lose it for another 20 years.”

Degas’s Portrait of Mlle. Gabrielle Diot has been a particular challenge. Displayed above Rosenberg’s desk in his Paris gallery, it fell into the hands of the German ambassador. He moved it to Paris’s Jeu de Paume, where many other looted works from Jewish collections were stored during the war. The Rosenbergs had no idea of its whereabouts until 1987 when it appeared in an art magazine ad from Hamburg art dealer Mathias Hans.

At the time, Rosenberg’s daughter, Elaine Rosenberg, made a phone call to Hans, who then asked that the family buy the work back. Rosenberg refused. According to the Times, a Swiss family had bought the piece in 1942 in Paris, and Hans oversaw the sale to the current owner, also based in Switzerland, in 1974 for 3.5 million Swiss francs ($3.5 million).

The 1987 sale fell through, but Hans tried again in 2003, asking €3 million ($4.6 million) for the work. But the potential buyer, a German businessman named Christian von Bentheim, backed out when he learned that the portrait is included in international databases of looted art.

Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Officer James Rorimer supervises US soldiers recovering looted paintings from Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany during World War II. Photo courtesy of the US National Archives and Records Administration.

Some 50 countries signed 1998’s Washington Principles and the 2009 Terezin Declaration, pledging to stand behind efforts to provide restitution for Jewish art collectors whose belongings were looted by the Nazis, or sold under duress. Results have been mixed, but a major research project in the Netherlands recently identified 170 potentially stolen works of art and is looking to begin restitution proceedings.

Nevertheless, the Rosenbergs are unlikely to bring a lawsuit against Hans, as the statute of limitations under German law makes restitution difficult. But since 2016, they’ve enlisted Art Recovery International, based in London, to help them with their case. The organization is helping keep the pressure on Hans, recently enlisting an official from the German Culture Ministry to contact the dealer and ask for information about the painting’s owner. Hans responded by asking that the Rosenbergs reimburse his client in full for the artwork’s return.

Dissatisfied with the unsuccessful efforts of the German government, Art Recovery International issued an announcement imploring anyone who may know details about the painting’s owner or whereabouts to contact them, assuring would-be informants that “information will be treated with the strictest confidence.”

“The professional art market does not look favorably on dealers who demand ransoms for the return of Nazi-looted artworks,” said Art Recovery International’s Christopher Marinello in a statement. Mr. Hans’s behavior belongs to a bygone age and he risks his reputation, and the trust of his clients, by continuing to deceive.”