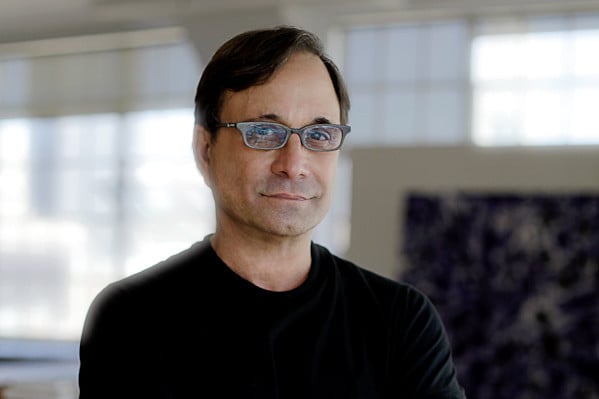

Image: Marcus Andersson

New York artist Ross Bleckner has work in six new shows on now or opening soon, including his first solo show in the Middle East, opening in April at Leila Heller Dubai, followed by what is sure to be the art happening of the Hamptons this summer, a group show that unites him with his fellow 80s art-world it-boys David Salle and Eric Fischl at the Parrish Art Museum on Long Island.

While this much attention is akin to what Bleckner enjoyed in his heyday in the early 1990s, don’t call it a comeback. “I don’t like to use that word,” says his New York gallerist Mary Boone, in an interview last month in her uptown gallery overlooking a corner of Central Park. Before Boone struck out on her own, she first showed Bleckner’s work in 1977 at her loft on Bond Street; she has mounted a Bleckner show every couple of years since 1983.

And Boone is able to do that because, through booms and busts, much like New York (the city with which he has become closely identified), Bleckner just keeps at it. He works. And he re-works.

Indeed, among the six shows—even those that include artwork that was not yet dry during a late January interview in Bleckner’s Chelsea studio—viewers will see paintings with deep roots in the last century, as far back as the 1970s, from several series that brought Bleckner fame—”Dome,” “Stripe,” “Bird,” and “Burn,” as he calls them.

To some, Bleckner may be known less for his work than as a namecheck on an early episode of the television show Sex and The City in which Kim Cattrall’s character sleeps with a guy who offers to show her his newly acquired Bleckner painting. Or from the society and gossip pages where, according to the New York Times’s Michael Kimmelman, Bleckner’s name was mentioned “as often as his friend Bianca Jagger’s.”

Mary Boone and Ross Bleckner circa 1991.

Image: Courtesy of Mary Boone

In 1995, Bleckner was the youngest artist ever to have a major solo show in the rotunda of New York’s Guggenheim in the museum’s nearly six decades of existence.

Then came several less than encouraging reviews presaging that collectors might cool on Bleckner soon into the new century. Kimmelman accused Bleckner of appropriating Op Art and making it about AIDS. The critic railed against the artist for replacing the genre’s bright colors with a muted (if not sober) palette and for abstracting—through the patterns, tropes, and titles of his artwork—not only the virus but also the fear of death among gay men in that era. Kimmelman acknowledged Bleckner’s tireless advocacy on this issue but went as far as to say “it’s hard to know whether it is better for him that it be thought of as sincere or as ironic, because if the first, he is a sentimental purveyor of pseudo-Victorian kitsch, and if the second, he is exploiting a serious issue.”

Three years later, Roberta Smith, parroting some of Kimmelman’s language, took Bleckner to task for his ubiquity: a museum show and two gallery shows. (Today one would call it synergy).

She criticized his then-current ads for Absolut vodka. And then she went all-out with adjectives, calling one series of paintings “dull and pointless,” another “greasy, finicky and way over the top” and signaling what she saw as his work’s “extreme” sentimentality.”

But disparagement from one’s hometown paper, even if it is the paper of record, does not a career-ender make. Bleckner kept painting and kept selling. He had nearly five years of steady prices from 1988 to 1993, when his total sales value ranged from $151,305–357,555, respectively, according to the artnet Price Database. Then, in 1994—just before his Guggenheim show—his total sales value fell to $58,650 (though only four pieces came up for auction that year). But his sales reflect steady growth, which also suggests that activity in his market is not speculative.

Ross Bleckner, Mary Boone, and Eric Fischl ca. 1985.

Image: Courtesy of Mary Boone

The number of Bleckner works offered at auction has risen steadily over the years, from eight in 1988 to 45 in 2015. And it might surprise some that the highest price ever achieved at auction for a work by Bleckner—who has been criticized for his meteoric rise and subsequent ubiquity—is just $192,000. The sale was in 2006 for Oceans, a canvas from his Stripe series (described by the Times in 1987 as “among the most sought-after works of any contemporary artist”). By contrast, the records at auction for his peers in the upcoming Parrish show are $576,000 for Salle and just under $2 million for Fischl, both also achieved in 2006.

But auction prices aren’t the full picture, of course. Boone emphasized that the auction price does not necessarily reflect value. “Remember that when Andy Warhol died in February 1987,” she said in an email, “his top price was $650,000; as opposed to Johns who had already sold for $17 million or Rauschenberg at $6.3 million.”

Ross Bleckner, Untitled (2015).

Image: Leila Heller Gallery.

Boone maintains that Bleckner’s work is very undervalued. “That is why many of them buy the work,” she said, “including Andy Hall, who is one of the smartest and most sophisticated collectors out there.”

Now that years have passed since he first stirred the art world, it’s back to the future for Bleckner with the show this summer at the Parrish. “Unfinished Business: Paintings from the 1970s and 1980s by Ross Bleckner, Eric Fischl, and David Salle” comprises work from those decades by the trio, who met and became friends at Los Angeles’s CalArts in the 1970s, and all gravitated to New York and Long Island’s East End in the 80s.

Even the exhibition’s title begs the question, “Where are they now?” But it’s too early in the Parrish’s curatorial process to know whether the museum will attempt to answer that question. We know one place where Fischl and Salle are not: the hallowed rooms of Mary Boone Gallery. Though Boone—who also represents Barbara Kruger, Ai Weiwei, and KAWS—built the careers of all three, only Bleckner is still with her. Salle and Fischl are both with Skarstedt Gallery, which announced its representation of Fischl this past November.

In the Parrish show, the Bleckner works, all from his own collection, comprise approximately 10 canvases (oil and acrylic) and eight works on paper (all oil, some with charcoal too), including a study for one of his well-known early Stripe paintings and a 1983 still-life of a vase with flowers redolent of Odilon Redon.

Then there’s the exhibit entitled “New Work” opening April 29 at Leila Heller’s gallery in Dubai, a 15,000-square-foot space that, according to Heller, became the biggest commercial gallery in the United Arab Emirates when it opened in November.

A rug from Ross Bleckner’s recent “Prayer Rug” series on view in New York.

Image: Cristina Grajales Gallery and Leon Tovar Gallery.

If it seems hard to imagine Bleckner succeeding with collectors in the Arab world given that he is gay and grew up Jewish, which would make him persona non grata in the region, then consider that among the works Heller is hanging are a half-dozen new Dome paintings, which build on the series that served as the cornerstone of his Guggenheim retrospective 21 years ago, and work from a newer series Bleckner calls Prayer Rugs.

Bleckner has long described his Dome paintings as inspired by the Pantheon and, even more so, the massive dome of Istanbul’s Hagia Sofia, the former Christian basilica that with the changing tides of history became one of the world’s most important mosques for nearly 500 years. He recalls first visiting what is now an awe-inspiring public museum in the mid-to-late 80s: “Hagia Sofia had been the M.O. of these paintings for a long time.”

The Dome paintings, through their scale and emphasis on flat, hand-painted surfaces, capture a feeling of the sublime while also emphasizing the artifice used to create its effect. “There’s an astronomy to it absolutely,” Bleckner explained, pointing out details in the newer works in his Chelsea studio, even as they were being crated for shipment to Dubai. Since Bleckner’s new technique involves using bleach to pare back the paint buildup, his newer Dome paintings appear more luminous, spatial, celestial, and even spiritual, in contrast to the more obviously architectural structures depicted in his earlier work.

Ross Bleckner, Dome (2015).

Image: Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery.

“I knew of the Dome paintings and every time I went to the Hagia Sofia I thought of Ross,” says the New-York based, Iranian-born Heller. “I had been planning the Dubai gallery for seven years, and so for years, showing him and his Dome paintings in particular was always in the back of my mind.”

Spirituality and prayer also play into his newer Prayer Rug series, begun about three years ago, he says. The rugs feature personal prayers composed by the artist, and rendered in his own handwriting in silk and wool, like this one:

I pray to feel complete, comfortable and calm to not judge myself harshly and to cultivate compassion so that I can understand others and their suffering // I pray to see the world as a loving, giving, and trusting place so that I can open my heart to beauty, romance, amazement, and joy.

These are Bleckner’s most obviously personal works ever. “I don’t like to reveal that side of me, but it comes out in your work anyway,” he says, “which is always the interesting part.”

A detail from one of Ross Bleckner’s bird paintings (2015).

Image: Courtesy of Leila Heller

Indeed, the art works destined for Dubai are rooted in Bleckner’s own spiritual and social practice, which both he and Boone cited as inextricably linked to his artistic practice, and something that distinguishes him from some of his peers who came of age and gained recognition in the same era. This includes Bleckner’s much-lauded work for HIV and AIDS research and his commitment to young artists, especially those he has taught for more than a decade at NYU’s Steinhardt School.

Related to his role as a master is Bleckner’s inclusion in two group shows that opened quietly during the mayhem of New York’s Armory Week and are on view through April 16. First, there is the cleverly conceived exhibition, “The Making: Artists, Assistants, and Influence,” at New York’s Luxembourg & Dayan, which includes a Bleckner oil on linen, Burn Painting (2015). The show posits a family tree of artists who go on to respond to techniques of their progenitors. Then, another 2015 painting that is part of the Burn series is also in a group show, “Nice Weather,” on view at New York’s Skarstedt Gallery. Curated by Salle, the show borrows its title from a Frederick Seidel poem about how tomorrow’s weather comes from today’s and highlights multiple generations of painters from Rosemarie Trockel to Sterling Ruby.

Additionally, four Prayer Rugs from 2015 and one Prayer Painting are also on view in New York at Third Room, the collaborative art-meets-design space by Leon Tovar Gallery and Cristina Grajales Gallery. And a smattering of recent Bleckner paintings will also be on view beginning May 1 at Rafael Jablonka’s Böhm Chapel in Hürth-Kalscheuren, Germany.

When talking about everything Bleckner has going on right now, Boone leads the conversation back to his legacy; she compares Bleckner to “a John Miller, a Jim Shaw, a Barbara Kruger” whose importance is not just in the ongoing work but, as a member of the establishment, both in his pedagogy and in “how many young artists follow them.”

“In the Making: Artists, Assistants, and Influence,” through April 16 at Luxembourg & Dayan, 64 E. 77th Street, New York

“Nice Weather” through April 16, at Skarstedt Gallery, 550 West 21st St. and 20 East 79th St., New York

“Ross Bleckner: Prayer Rugs,” through April 29 at Third Room, 152 West 25th Street, 3rd floor, New York

“Ross Bleckner: New Work,” April 29 through June 15 at Leila Heller Gallery, I-87 Alserkal Avenue, Al Quoz 1, Dubai, UAE

“Architecture of the Sky,” May 1 through Oct. 31 at Böhm Chapel, Hans-Böckler-Straße 170, Hürth-Kalscheuren, Germany

“Unfinished Business: Paintings from the 1970s and 1980s by Ross Bleckner, Eric Fischl, and David Salle,” July 31 through October 16 at the Parrish Art Museum, 279 Montauk Highway Water Mill, NY