“Why, in the most powerful and richest nation in the world, at a time when America leads the world in science and technology, are many of its most talented artists playing with dolls?” An excellent question, this is how painter Eric Fischl spins his newest curatorial effort, “Disturbing Innocence,” in a recent conversation with the magazine Dazed and Confused. Though a virtual American Girl store, Fischl’s crowded exhibition leaves one short on answers. This proves doubly true when one looks, mostly in vain, for a robust rationale for what is a star-studded, but conceptually confounding affair.

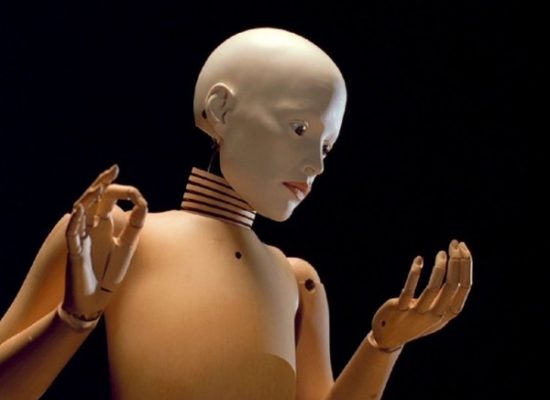

A large group-show Fischl organized for Chelsea’s Flag Art Foundation, “Disturbing Innocence” packs together 87 artworks by 58 historical and contemporary artists into two floors of the Chelsea Arts Tower. The exhibition purports to explore the use of effigies as an artistic “genre,” yet consists of little more than a roll call of popular works that employ kiddie surrogates—dolls, toys, robots and mannequins—to trace what the exhibition release terms “a subversive and escapist world at odds with the values and pretensions of polite society.” Like Fischl’s memorable 1980s paintings, “Disturbing Innocence” works best as a group of single pieces that dwell on childhood’s loitering traumas; conversely, it flounders whenever adult connections struggle to be expressed.

Divided into three unfocused sections, the exhibition reveals a congested display the minute the elevator opens onto the Flag Art Foundation’s 9th floor. There, in less than twenty square feet of space, are arrayed Claudette Schreuders’ carved twin wooden figures The Third Person, Gregory Crewdson’s C-print Untitled (Empty House), Amy Bennett’s intimate oil painting Property Line, James Casebere’s setup photo Landscape with Houses (Dutchess County) #9, Will Cotton’s candy-themed canvas Brittle House, and a Roy Lichtenstein bronze abode painted in Mondrian primaries—red, yellow and blue. These paintings, sculptures and photographs introduce the section Fischl calls “Suburban Idyll (or not).” Compared with the ersatz baronial Levittowns and Greenwichs that are these works’ inspiration, Fischl’s use of gallery space is an exercise in co-op living.

Aura Rosenberg, Laurie Simmons/Lena Dunham, 1996-1998.

Like curators with a fraction of his experience, Fischl routinely fails to distinguish between art that is merely related to his subject, and objects that are indispensable to developing the exhibition’s overall theme. Though hung cleanly, the show’s other two sections—they are prosaically titled “Mannequins, Morphs and Robots” and “Boys will be boys and girls will be…”—are jammed together so tightly as to resemble a garage sale, but in a toolshed. As a consequence, “Disturbing Innocence” comes off as substantially less than the sum of its parts. Half of the art in the show could easily command the Flag Foundation’s entire footprint.

As it is, “Disturbing Innocence” delivers mostly boilerplate pairings together with disparate if familiar artwork in various media. There are Mike Kelley’s stuffed animals, Two Frogs/Two Cats, hung high above E.V. Day’s five framed Mummified Barbies and John Wesley’s Caryn and Robin, the painter’s sign-like treatment of two limber prepubescents. But there’s also Richard Prince’s Spiritual America, the artist’s famous fair use “transformation” of a 1976 photo of a naked, oiled 10-year-old Brooke Shields. Like with the uninspired colocation of the Kelly work, the placement of Prince’s image between a Laurie Simmons/Lena Dunham portrait of Dunham made up to look like Howdy-Doody and Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinooodh Matadin’s portrait of a young blissed-out girl Kirsten, Star reinforces an obvious angle, cue observations about childhood celebrity. Yet it does that superficially, too, turning Prince’s infamous act of artistic appropriation into outsider doll photography—like the more conventional camera perversions enacted elsewhere by shutterbugs Dare Wright, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, and Morton Bartlett.

Never as disturbing as a single New York Times story about Jerry Sandusky or one of Fischl’s own angsty Town and Country narratives, “Disturbing Innocence” also fumbles the celebrated curator’s own individual contribution. It consists of a rough-hewn male bronze with a hard-on, done in the sincere but intentionally clumsy style of the artist’s controversial Tumbling Woman (the artist is on record as saying that the public fallout from that sculpture’s brief residency at Rockefeller Center left him “confused and hurt”). It might have been far simpler and stranger to include something more voyeuristic and less self-referential; say, for example, the artist’s genuinely creepy Girl with Doll from 1987.

But this questionable politico-aesthetic decision itself is typical of the problems with “Disturbing Innocence”—along with a general bagginess, it helps push the show’s subject matter into a truly strange arena that recalls the embarrassments of the 1990s men’s movement and the bloviations of Robert Bly (a discussion in the exhibition catalog between the curator and participating artists Lori Simmons, Cindy Sherman and David Salle includes an awkward discussion about female biology). The justly celebrated Fischl did well to pull in friends and non-friends into a show of disturbing stuff that, unfortunately, channels remarkable curatorial innocence. Flaws aside, it’s all too easy to see how a radical edit might squeeze an original idea or two from this oddly innocuous exhibition.