Reviews

The RA’s Russian Show Is a Fascinating Survey of Life and Art During the Revolution

From hope and heroism to censorship and deportation, it’s all here.

From hope and heroism to censorship and deportation, it’s all here.

Hettie Judah

“Revolution,” the exhibition at London’s Royal Academy of Arts devoted to Russian art created between 1917 and 1932, is not, to be frank, a bundle of laughs. And thank god, for it to be otherwise would be lamentably poor taste, the stuff of naïve student poster displays.

From the opening room, we are introduced to two parallel worlds of art and image making. In one, we find the “approved” version: all noble, staunch and muscle-bound in its depiction of leaders and workers alike. In the other, its shadowy obverse—works such as Georgy Rublev’s depiction of Stalin relaxing with his dog in a rattan chair—that have been hidden for decades in attics, bottom drawers, and archives, condemned for their failure to show the sanctioned version of the truth.

Between the first stolid, heroic depictions of Lenin in life and death, and the exhibition’s closing portraits of athletic heroism, “Revolution” does not shy away from a wider context that includes starvation, oppression, censorship, deportation, forced labor, imprisonment, and executions. A room of remembrance toward the end offers a roll call of those arrested and sent to the gulag: artists and “ordinary citizens” alike. Some were shot, some died, a tiny fraction survived until release.

It might be more useful to think of “Revolution” as an exhibition about art and representation rather than an exhibition of art. The curators have chosen to include some terrible paintings, largely dedicated to the cause of political flattery and propaganda. There are likewise sentimental figurines romanticizing the life of the honest peasant, and clunky tableaux of compliant factory workers. All earn their place in building up the larger picture of what happens to art when it is bent to the service of political narrative.

Marc Chagall, Promenade (1917-18). Photo ©2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, ©DACS 2016.

There are, nevertheless, moments of beauty, grace, and even levity here. Pavel Filonov’s dense, map-like Formula of Spring (1927-29) coruscates with spiritual optimism. In one high, circular gallery turns a suspended recreation of one of Vladimir Tatlin’s elegant and utopic gliders. And for joy, you don’t get much better than Marc Chagall’s Promenade (1917-18), showing the artist in love, with his wife floating in a cloud of adoration at the end of his arm in the early, hopeful days after the October Revolution.

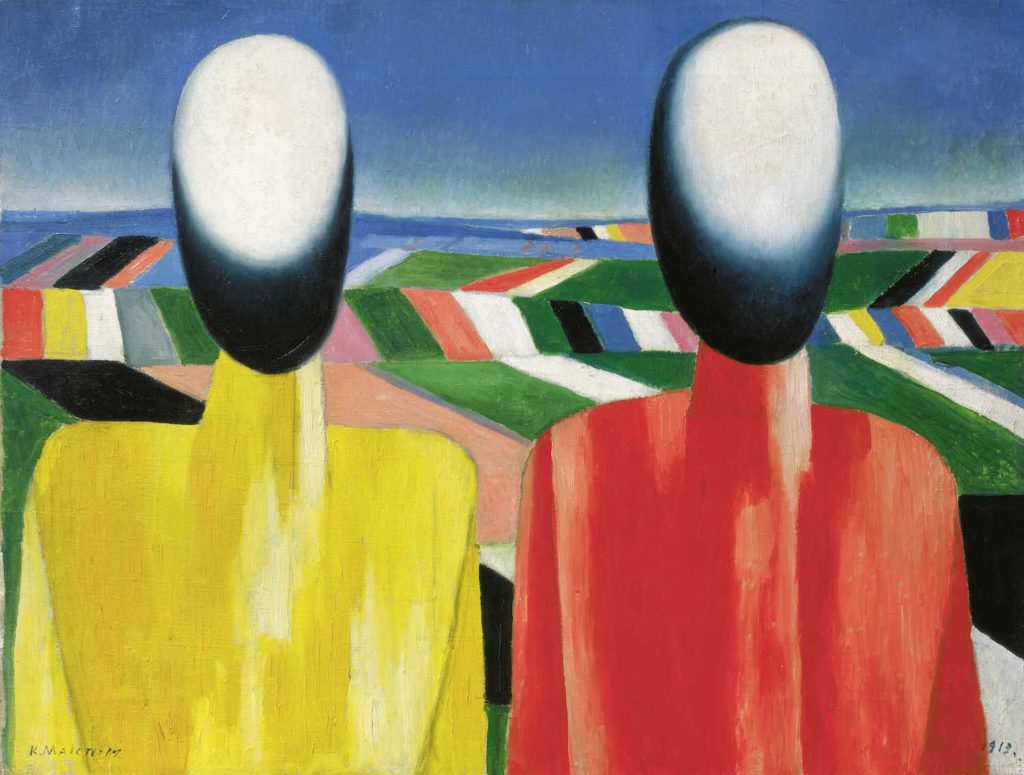

The curators achieve a number of significant art historical coups, notably a display of some 30 works by Kazimir Malevich arranged as they were in the 1932 exhibition “Artists of the Russian Federation over 15 Years.” A late Black Square hangs high on the wall beside Red Square. Displayed beneath them are Suprematist compositions, pictures of peasants and jockeys, and three displays of his “architectons.” Painted in 1930, Malevich’s peasants are anonymous figures offered void and faceless, a far cry from the approved apple-cheeked vision, and hauntingly suggestive of the de-humanizing impact of collectivization.

On the other side of the room, rather surprisingly, is a display of crockery printed with Suprematist designs, some by Malevich himself, some by his followers. Hardly the kind of “artist collectible” that one usually finds advertised at the back of the Sunday color supplements, they are emblematic of a period between 1917 and 1928, during which the avant-garde felt in some way expressive of revolutionary dynamism.

Wassily Kandinsky, Blue Crest (1917). Photo ©2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.

Visual art did not exist in a vacuum, but was informed by and nourished on developments in film, photography, theater, design, graphics, and poetry. In a central room dedicated to this productive period, “Revolution” presents works by Wassily Kandinsky, alongside a full-sized recreation of a worker’s apartment designed by El Lissitzky, and short films illustrating theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold’s “biomechanics.”

In a brilliant (and unsignposted) coup de théâtre, the ceiling of this ornate, neoclassical gallery is hung with recreations of the abstract forms designed by Nathan Altman for Palace (then Uritsky) Square in St. Petersburg for the first anniversary of the revolution in 1918. Modern forms intended to accompany a mass celebration of the modern order; following Trotsky’s fall in 1928, abstract works such as Altman’s were condemned as “bourgeois.”

Alexander Deineka, Textile Workers (1927). Photo ©2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, © DACS 2016.

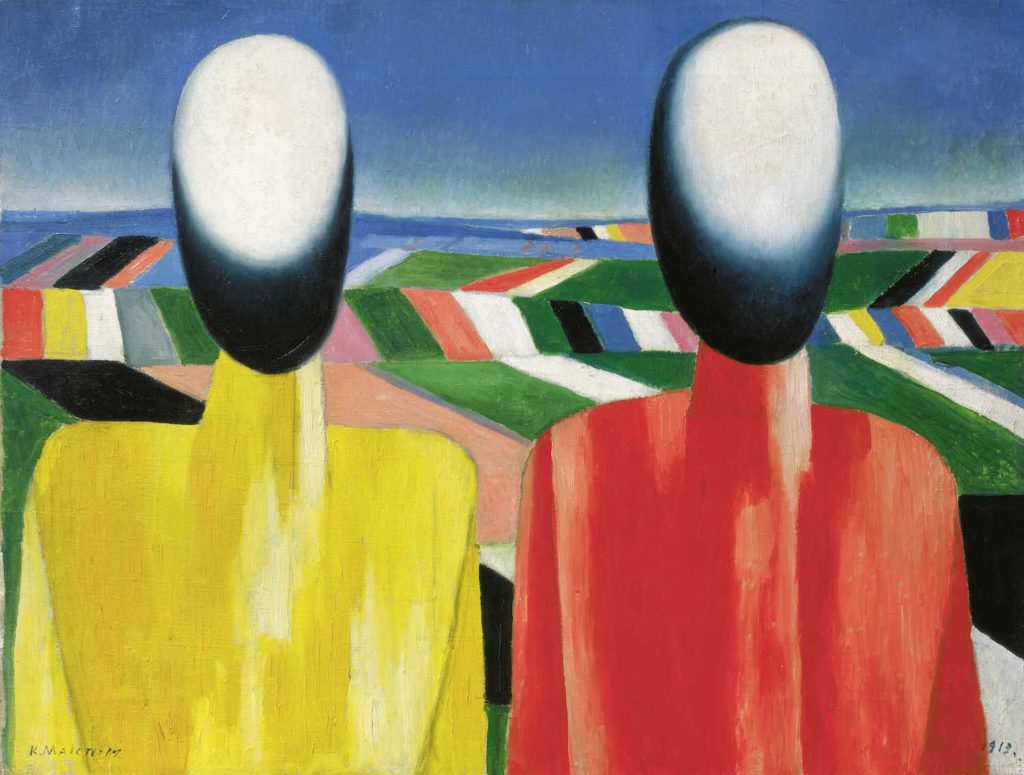

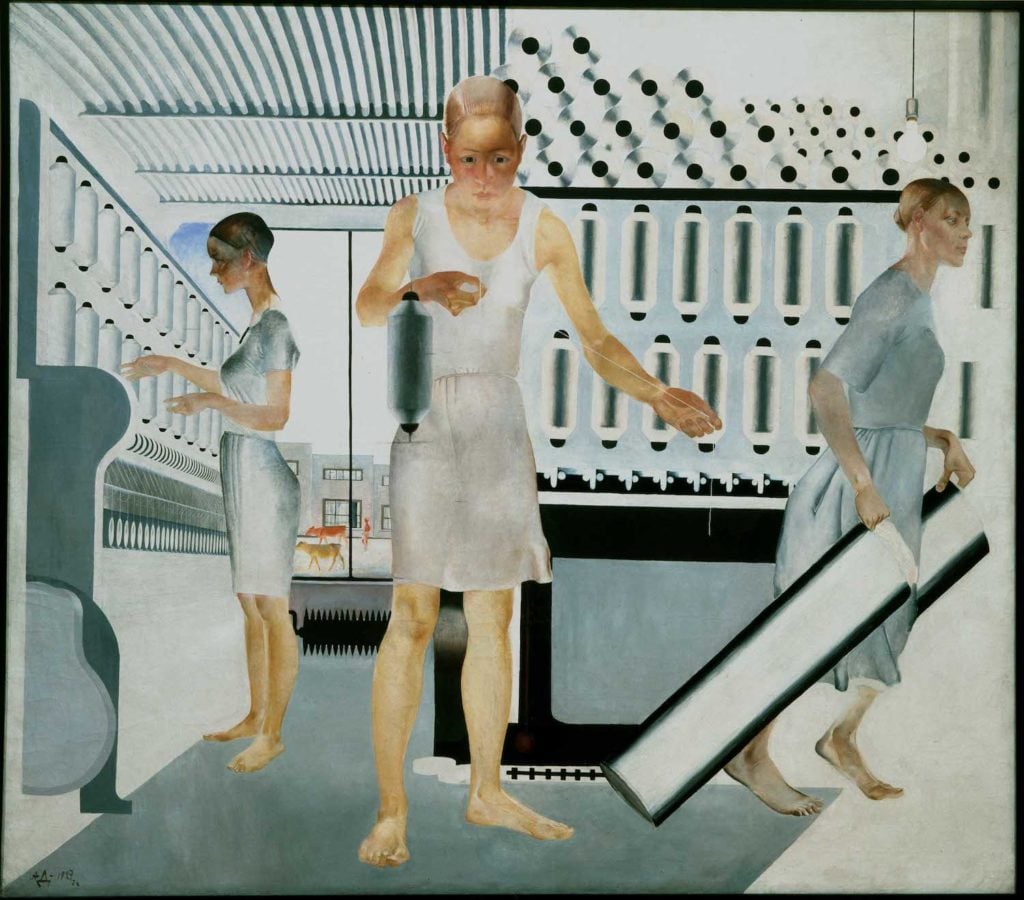

It would be overly reductive to condemn all works approved by the state, and “Revolution” negotiates a path that allows for appreciation and discovery. From Arkady Shaiket we find beautifully composed photographs of muscular komsomol working glossy mechanisms, or engineers constructing the Moscow Telegraph Centre. There are strikingly modern early works by Alexander Deineka, such as Textile Workers (1927), which pre-date the imposition of the approved Socialist Realist style with which his later work became synonymous. Konstantin Yuon’s radiant New Planet (1921) presents the October Revolution as some kind of cosmic event, a red sphere rising above a new dawn, in the light of which we see half-naked humanity both cowering and jubilant.

In an unexpected change of pace, a large room is dedicated to Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. An artist whose work is less familiar to UK audiences, Petrov-Vodkin trained in icon painting, but later developed a sensual style and “spherical perspective,” in which the image curves inward toward the viewer as if making visible the curvature of the earth. While Petrov-Vodkin’s work largely escaped the damning “bourgeois” label, the banning from exhibition of his battle scene Death of a Commissar (1927) indicates how sensitive Soviet officials were to any suggestion of criticism.

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Fantasy (1925). Photo ©2016, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg.

Petrov-Vodkin is the only artist, save for Malevich, whose work is afforded so large a display, and this surprising move so close to the end of the exhibition characterizes the piecemeal nature of Revolution. Perhaps the curators felt that they could not do justice to so complex a theme in a more neatly-packaged exhibition, who knows? “Revolution” has much to offer, whether great art or merely thought provoking. Just don’t go expecting to be entertained.

“Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932” is on view at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from February 11 – April 17, 2017.