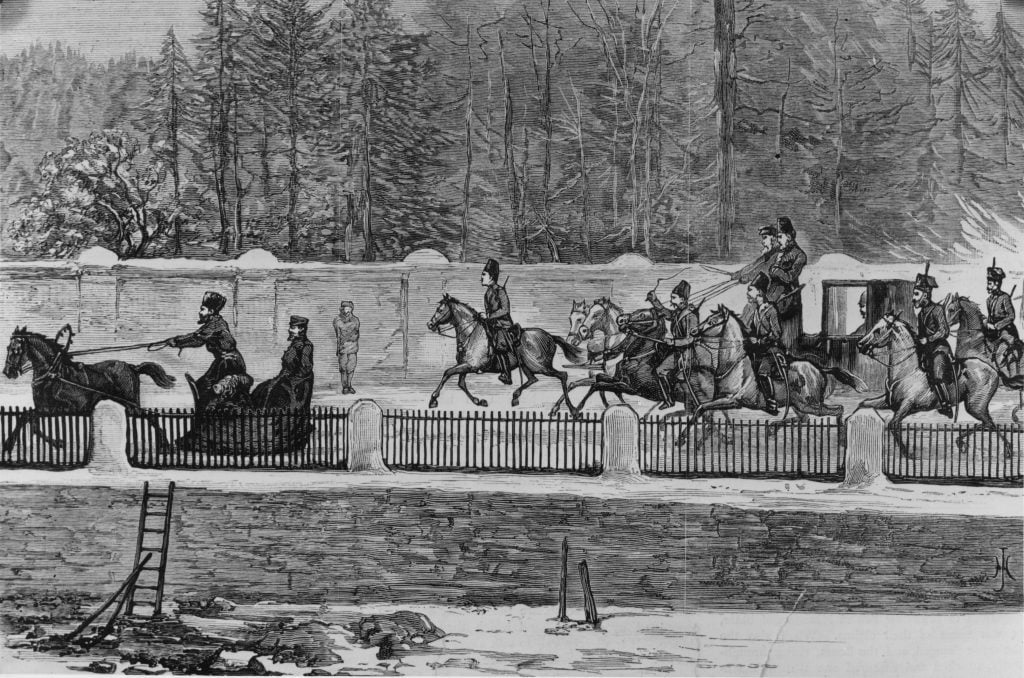

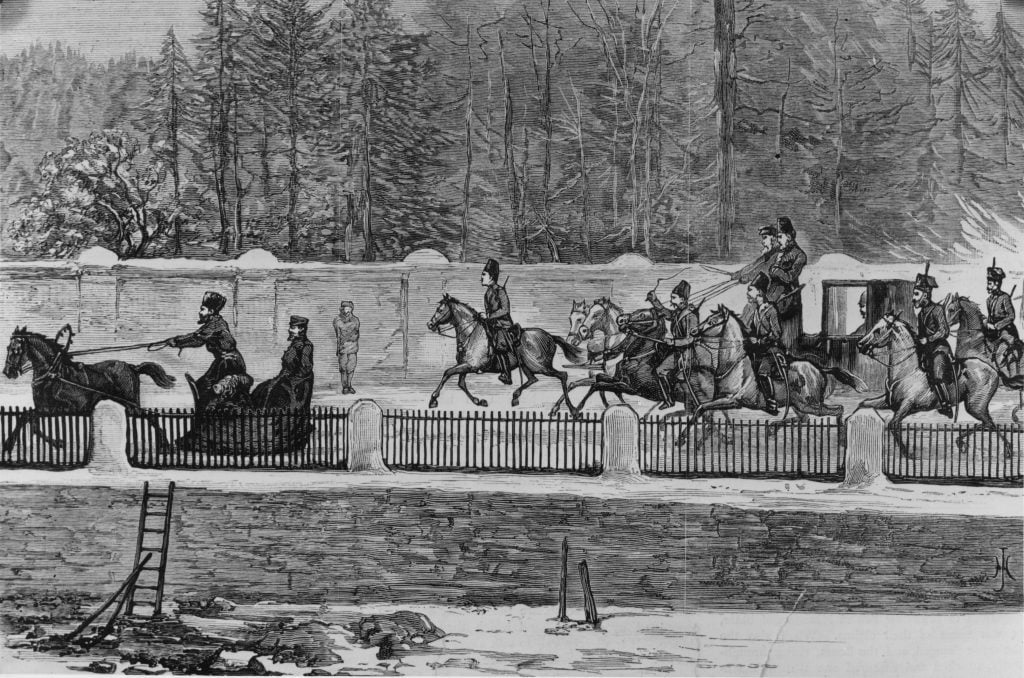

A tall tale of a horse named Varvar is the link between two historic political opponents explored in Kirill Savchenkov’s ethereal sculptures. Tsar Alexander II was assassinated in a carriage bombing in 1881, and carried away by Varvar. According to the 36-year-old Russian artist and myth-maker, that horse was also the means of escape from political prison for the influential, anti-imperial theoretician Peter Kropotkin, who rode Varvar to freedom a few years earlier in 1876.

With floor-to-ceiling silhouette-string sculptures made out of horsehair and other materials, Savchenkov threads along the stories of these men and other 19th and 20th-century revolutionaries, in the moving exhibition, “The Stranded Horse and The Riderless Night,” on view at Galerie Allen in Paris until Feb. 24.

13th March 1881: Tsar Alexander II traveling in a horse-drawn carriage at St Petersburg moments before he was mortally wounded by a bomb thrown at him. Original Publication: The Graphic – pub. 1881 (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Pin-pricked and laced together with weaver bird-like precision, these bouquet sculptures are made of found cicada wings, leaf skeletons, dried flowers, and shriveled, charred matches, along with burnt “tears of plastic,” and miniature silicone mask-portraits. Their web-thin parts flicker in and out of view, ready to float away, as easily as a shifting, forgotten memory. The installation is accompanied by a soundtrack that combines the sounds of a horse breathing and a violin being played with a horsehair bow (a double reference to the violin signal used for Kropotkin’s prison break).

It is impossible not to see a connection between Savchenkov’s escapist meditations and his own story. He withdrew from Russia’s pavilion planned for the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, to protest the invasion of Ukraine beginning on February 24 that year. On February 27, he posted on Instagram: “There is no place for art when civilians are dying under the fire of missiles, when citizens of Ukraine are hiding in shelters when Russian protesters are getting silenced.” Curator Raimundas Malašauskas, who wrote the Galerie Allen exhibit text, was also part of the pavilion artistic team who withdrew.

Around the same time, Savchenkov left Russia, his wife joined him soon after, and they made their way to France, thanks to a series of coincidences and chance meetings. Savchenkov doesn’t like to dramatize his situation, preferring to call himself an “immigrant for political reasons,” rather than an exile, because he is not under the kind of direct threat that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s political opponents face.

Kirill Savchenkov, Essay D: Vera’s Herbarium (2023) (Detail). Photo: Anna Denisova. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris.

In fact, Savchenkov doesn’t actually know what kind of danger he may be in, which the artist argues is precisely how the Russian government exercises control. It’s a concept the artist explores in his practice around “hidden political narratives,” and what he describes as “a new form of informal dictatorship” (which Savchenkov points out is not limited to Russia).

“My artistic practice focuses on a specific kind of political regime, which uses your emotions and uncertainty about social life,” he says, and explains that doubts about factual information and fake news are used as currency to “control society.”

Savchenkov is now living out the historic tradition of immigrant artists coming to Paris, often as political refugees—though he says he is not a refugee. He must remain demure, however, about mentioning artists in his circle out of concern for their safety. “It’s one of the results of this manipulation,” he said. “You don’t know if you’ll be arrested if you go back to Russia.”

Savchenkov uses varied mediums to suggest how we can perceive one thing, only to notice it is in the process of becoming something else, not unlike those “hidden” political narratives mentioned. Some works, for instance, include small, burned bits of plastic he calls “shapeshifting,” which look like insect waste or cocoons and are a reminder of the burned plastic remains of street protests and riots. “I try to find pinpoints,” that mark social experiences, he said, as well as where those points of contact tip into new forms.

Kirill Savchenkov Essay B: Escape (2023) (Detail). Photo: Anna Denisova. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris.

Savchenkov’s past performances and sculptures have been shown in Le Commun, Geneva, the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, and the 12th Gwangju Biennale, to name a few. But his previous work tended to be more massive than these recent, lighter pieces, made last year during a local artist residency run by Art Explora and before that, at the Cité des Arts. One reason is that their storage is a lot easier while on the move.

Though he feels a responsibility to address Russian politics and the invasion of Ukraine, Savchenkov stresses that his work has a more universal message in mind. “It’s a question of how we can struggle against dictatorship – not only Russian … And how we can understand our possibilities and our agency.”

The Russian revolutionary Vera Figner (1852 – 1942), is an example. In one sculpture dedicated to her “wordless diary,” called Essay D: Vera’s Herbarium (2023), the artist draws inspiration from her collection of plants while imprisoned in Russia’s Shlisselburg Fortress. Savchenkov threaded a silicone portrait of Figner into the piece, modeled from photographs of the revolutionary, who was also among the group who plotted Tsar Alexander II’s assassination. Like him, she eventually left Russia and settled in Paris.

“There are different kinds of agency,” Savchenkov said and pointed to Figner’s herbarium. “Your very existence, also, can be part of your agency.”