Ruth Asawa is the latest beneficiary of an increasingly retrospective art world that in recent years has frequently applied the benefit of hindsight to promote overlooked artists from the past worthy of a second glance.

Ten months after David Zwirner announced the representation of the Japanese-American artist’s estate, Asawa’s bulbous, balloon-like sculptures are on view at the gallery’s West 20th Street space in New York.

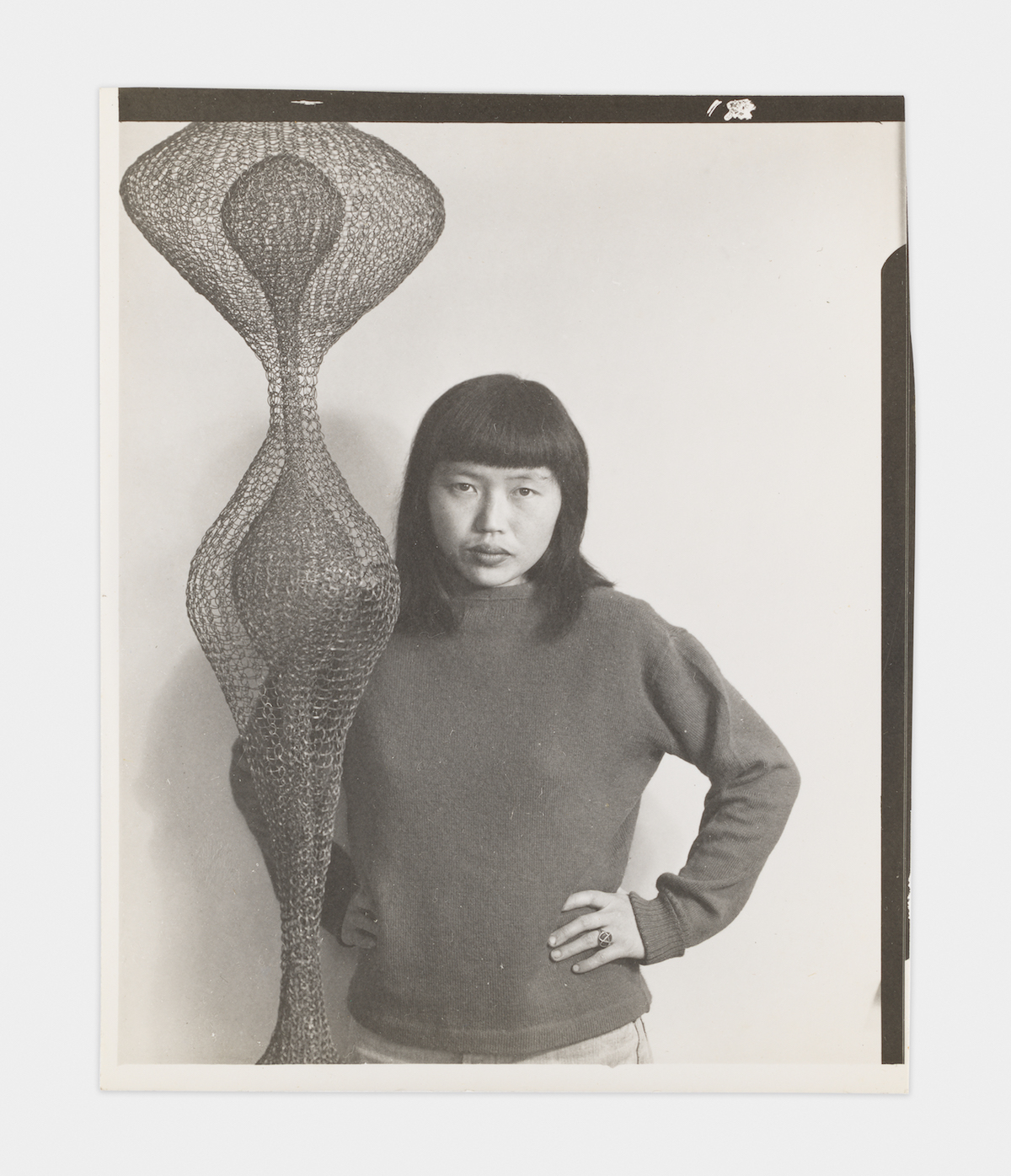

Photo: EPW Studio/Maris Hutchinson; Artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa

Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

Asawa started making art at an Arkansas internment camp for Japanese-Americans where she and her family were detained for several months in the wake of Pearl Harbor. Following her release in 1943, she studied to be an art teacher in Wisconsin only to have the Milwaukee State Teachers College discriminate against her for her ethnicity and obstruct her from student teaching. Instead, she enrolled at Black Mountain College in North Carolina where she studied under Josef Albers, Buckminster Fuller, John Cage, and Franz Kline.

Installation view of Ruth Asawa at David Zwirner. Photo: EPW Studio/Maris Hutchinson; Artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa

Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

Her stylistic epiphany happened during a 1947 trip to Mexico, where she observed craftswomen weaving semi-porous fruit and vegetable baskets, leading her to adopt a technique of weaving copper and iron wire into complex and intricate artworks designed to hang from the ceiling.

The art establishment didn’t quite know what to make of Asawa’s woven wire sculptures when they were first exhibited in the mid-1950s. At the time they were dismissed as “decorative” and “domestic,” labels commonly affixed to women or minority artists that didn’t fit the aesthetic norms of the time.

Photo: EPW Studio/Maris Hutchinson; Artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa

Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

Although major institutional recognition eluded Asawa during her lifetime (and largely still does), she lived to see the Guggenheim and the Whitney acquire her work, while market recognition came about four months before her death in 2013, when one of her works sold for $1.4 million at Christie’s. Today, the significance of her innovative practice is evident: By emphasizing lightness and transparency, and removing the sculpture from the pedestal, Asawa’s work challenged traditional and pre-existing definitions of sculpture. At the same time, she found a way to integrate her preoccupation with the drawn line into three dimensions.

Curated by Jonathan Laib, the longtime executor of Asawa’s estate, the survey exhibition at David Zwirner includes several major wire sculptures (including key loans from museums and private collections), rarely shown works on paper, and photographs of the artist by her friend Imogen Cunningham.

Photo: EPW Studio/Maris Hutchinson; Artwork © Estate of Ruth Asawa

Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

The museum-quality show is a crucial re-contextualization of Asawa’s work which belatedly reassesses her legacy within 20th-century art. It places her alongside other American greats that took sculpture off the pedestal and explored modular concepts, including Alexander Calder or Fred Sandback. The only remaining unanswered question is, why did it take so long?