The more you learn about the late Bay Area artist Ruth Asawa (1926–2013), the remarkable nature of her life and career becomes more and more apparent. Now, the Japanese American sculptor, painter, and printmaker is getting her first posthumous retrospective, with an international exhibition organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Five years in the making, the show will feature over 300 works of art, featuring the intricate looped wire hanging sculptures for which Asawa is best known. The exhibition will also showcase her works in a wide range of other media, including drawing, printmaking, paper-folding, and the many public sculptures still on view across the Bay Area.

“People will be really astonished to see what else she did,” SFMOMA chief curator and curator of painting and sculpture Janet Bishop told me. “She was somebody who was relentlessly creative. Everything she did, she did in her own way.”

“Ruth Asawa is an artist who is very exciting because of how seamlessly she integrated her art practice into her life. Material exploration was ceaseless, and she was a fierce art advocate, instrumental in bringing arts education into the Bay Area schools,” Cara Manes, MoMA’s associate curator of painting and sculpture, added.

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, (S.046a-d, Hanging Group of Four, Two-Lobed Forms), 1961. Collection of Diana Nelson and John Atwater, promised gift to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. ©2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy David Zwirner. Photo by Laurence Cuneo.

The artist grew up on a farm in Norwalk, California, until high school, when the government forced her family to relocate to a Japanese internment camp, first in California and later in Arkansas.

Asawa began pursuing art in college, studying at the famed Black Mountain College outside Asheville, North Carolina, with Josef Albers and Buckminster Fuller from 1946 to ’49. It was a fruitful time for the young artist, as she began adopting the line-based visual language and techniques that would characterize her work over the next six decades, including learning looped-wire basketry in Toluca, Mexico, in 1947.

After school, Asawa married one of her fellow students, the architect Albert Lanier. The two moved to San Francisco, where they would raise six children—two adopted, four biological—and live for the rest of their lives.

“When Ruth got to San Francisco, she was still in her early 20s. She knew she wanted to have a big family, and she knew she wanted to have a career, and it was important to her that those things were integrated,” Bishop said. “She did not feel the limitation of expectations for women, and didn’t feel like she needed to make a choice between art and family. Both were incredibly important to her.”

Ruth Asawa, Untitled (PF.293, Bouquet from Anni Albers), early 1990s. Private collection. ©2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy David Zwirner. Photo courtesy Christie’s.

Asawa worked tirelessly, reportedly sleeping as little as four hours a night. When the children were in bed, she made work. And her unique practice was shaped by the realities of childcare.

“Unlike working with oil painting, for instance, where it’s harder to put something down and and then go into the kitchen and tend to the pot of soup, she worked intentionally with materials that that could be put down and picked back up again,” Bishop said.

Asawa’s woven sculptures were sometimes dismissed as belong to the realm of craft, or women’s work—a 1956 ARTnews review called them “‘domestic’ sculptures in a feminine, handiwork mode.”

Nonetheless, she secured New York representation with Louis Pollack. He gave her three solo shows at the Peridot Gallery in the 1950s—until Asawa decided to step away. (The retrospective will include a display of works she showed in New York.)

“She was beginning to have a kind of market career. She was getting commissions,” Manes said. “Her kids were toddlers or newborns at that point. She just made a decision to focus on other things and not need to meet the demands of this burgeoning market that was being made for her.”

Ruth Asawa, Untitled (S.433, Hanging Nine Open Hyperbolic Shapes Joined Laterally), ca. 1958; William Roth Estate. ©2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy David Zwirner. Photo by Laurence Cuneo.

That market would stay largely paused for decades, until mere months before Asawa’s death, when one of her works sold for $1.4 million at Christie’s New York. Her profile has continued to rise in the decade-plus since, with mega-gallery David Zwirner taking on representation of the estate in 2017. (Her current auction record of $5.3 million was set at Christie’s New York in 2020, according to the Artnet Price Database.)

But while she did not pursue art world fame during her lifetime, Asawa remained dedicated to her practice. Her sculptures, with their interlocking lobes and nested forms, remain instantly identifiable, despite each one being unique. SFMOMA gave Asawa a mid-career retrospective in 1973, and she became well known across the city for her public monuments.

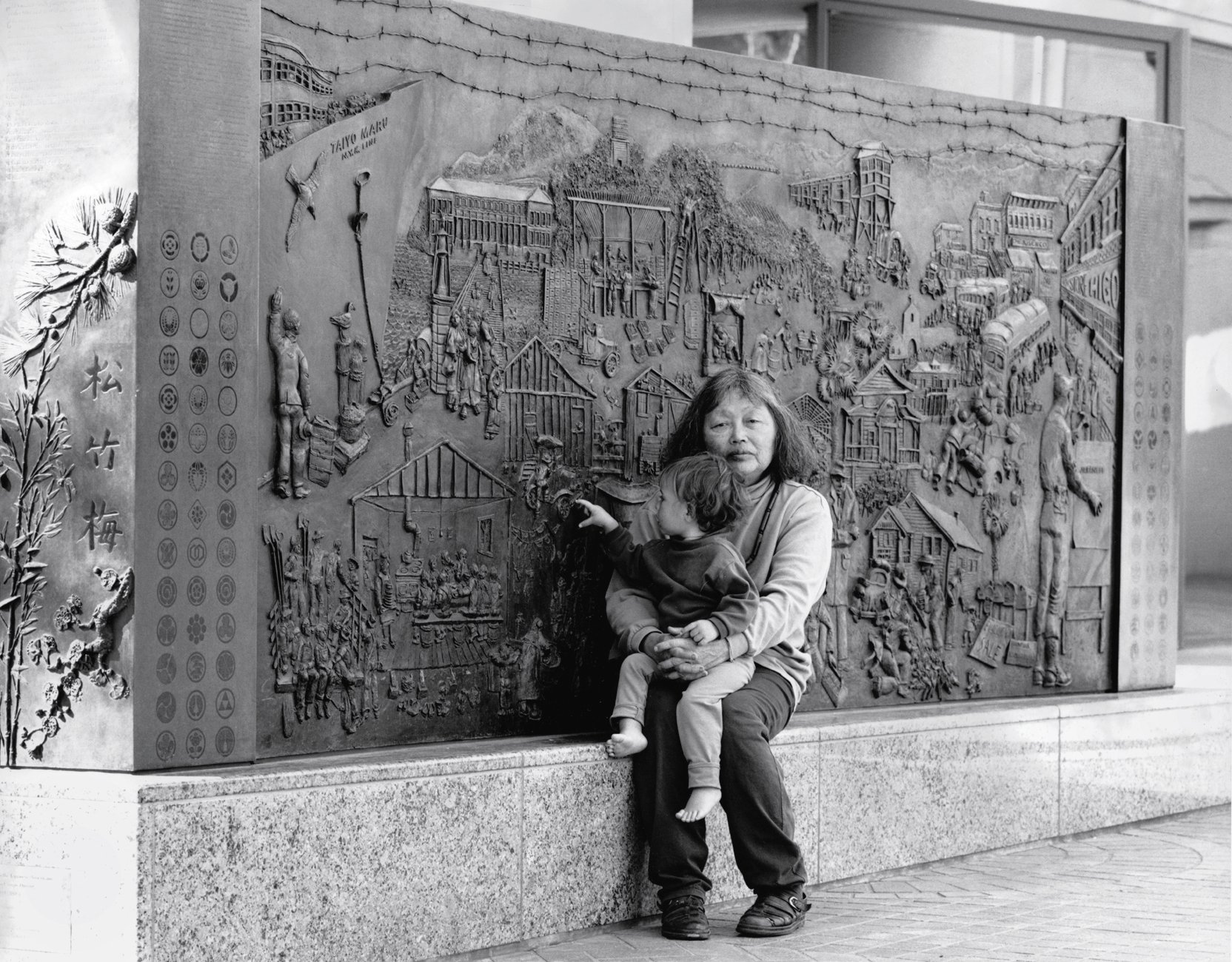

Some of these projects were collaborations with children, teaching them to sculpt with baker’s clay, made from flour, salt, and water. For San Francisco Fountain, outside the Grand Hyatt San Francisco, Asawa worked with children across the city to model the tiny scenes in relief sculpture for a drum-like basin she cast in bronze.

Ruth Asawa, Andrea (PC.002), 1966–68; Commissioned by developer William M. Roth for the renovation of Ghirardelli Square. 900 North Point Street, San Francisco. ©2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy David Zwirner. Photo by Aiko Cuneo.

Asawa began working with kids because of her passionate belief in arts education. She cofounded the grassroots Alvarado Arts Workshop, which ultimately blossomed into a citywide commitment to arts education in San Francisco public schools. She was a champion for the founding of a dedicated School of the Arts in 1982, which was renamed in her honor in 2010.

The exhibition will delve into Asawa’s incredible work with the community, but also remain rooted in her home and studio in San Francisco’s Noe Valley. One of the galleries at SFMOMA will be inspired by the space, placing the home’s nine-foot-tall carved Redwood doors at the entrance.

“She lived with the work that she was making—and that of others who were important to her, by friends and mentors like Josef Albers,” Manes said. “We’re planning a gallery that really communicates this seamlessness between living and art making, life and art, and between the home and studio.”

“Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective” will be on view at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 151 Third Street, San Francisco, California, April 4–September 2, 2025; the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, New York, New York, October 19, 2025–February 7, 2026; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Abandoibarra Etorb., 2, Abando, 48009 Bilbo, Bizkaia, Spain, March 20–September 13, 2026; and Fondation Beyeler, Baselstrasse 101, 4125 Riehen/Basel, Switzerland, October 18, 2026–January 24, 2027.