People

Star Costume Designer Ruth E. Carter on Fashioning Afrofuturism

The Oscar winner behind the iconic looks on 'Black Panther' is the subject of 'Afrofuturism in Costume Design,' currently on view at the Charles H. Wright Museum.

Ruth E. Carter has her plate full. When I reach her over the phone in Atlanta, Georgia, she rattles off a slew of projects on her slate: the forthcoming Eddie Murphy vehicle The Pickup, Marvel’s Blade reboot, and a hush-hush production led by filmmaker Ryan Coogler. It’s the schedule of an Oscar-winning costume designer, but even before she was twice–anointed by the Academy, Carter was already in demand.

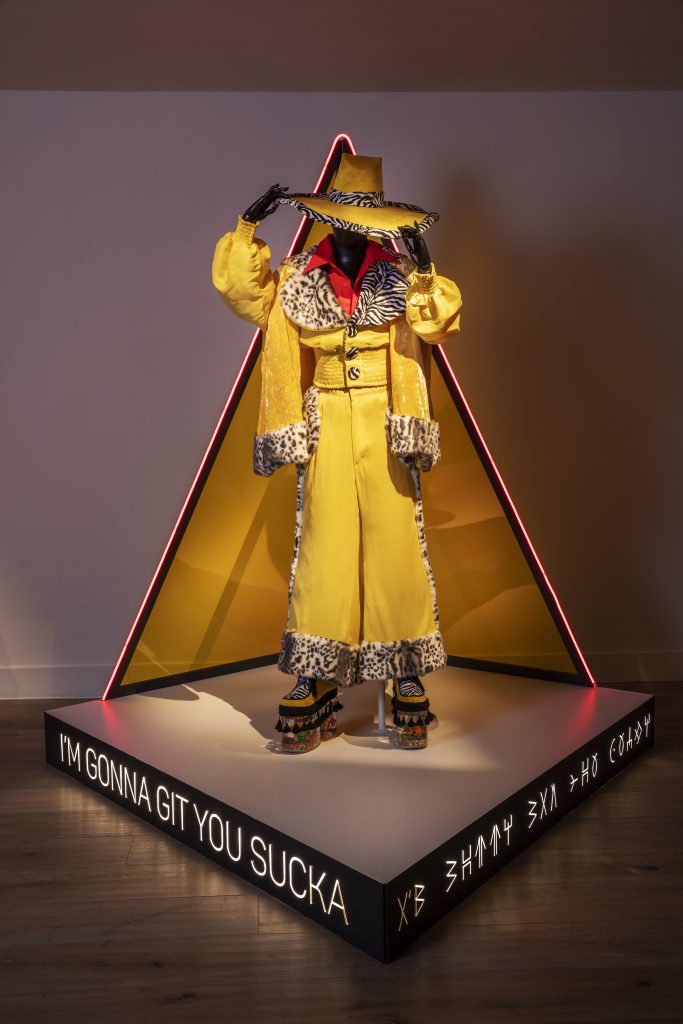

The rich scope of her nearly four-decade career is now on view at “Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design,” a traveling exhibition that runs through March 31 at the Charles H. Wright Museum in Detroit. The show gathers Carter’s costume designs for films such as Do the Right Thing (1989), Malcolm X (1992), Black Panther (2018), and Dolemite Is My Name (2019), alongside artifacts, notes, and sketches that bear out her creative process. Here, Carter’s deep research, craft, and prolific output are brought to the fore.

“Each film was a feat unto itself. Each one has its own unique story,” she told me about the works on view. “To see them assembled together really does feel like a career, a life’s work.”

Installation view of “Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design” at SCAD Fash, the Museum of Fashion + Film. Photo courtesy of SCAD.

Carter got her start in the 1980s designing costumes for theater and opera. During a stint at the Theater Center in Los Angeles, she met Spike Lee, commencing a partnership with the director that continues today. Other film and TV work followed—Amistad (1997) and Selma (2014) among them—and each furthered Carter’s commitment to humanizing onscreen Black narratives. Her vivid costumes for Marvel’s superhero outings, Black Panther and Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022), for which she exercised her world-building muscles, made her the first Black woman to win multiple Oscars in any category.

As her exhibition continues to tour—beginning in Atlanta, it has made stops in Roanoke, Seattle, and Raleigh—I caught up with Carter for a conversation about her design journey, her busy fitting room, and what it means to capture the African American experience in dress.

What’s it like to see your body of work fill a whole exhibition?

It’s a little surreal to see everything together. You don’t get that same impact as you go along the road. From one movie to the next, you feel the same. I feel I’m still the Ruth Carter I was when I started doing School Daze. But when you see it all assembled, you realize you’ve grown.

How so?

I think of School Daze or Do the Right Thing and how it was very grassroots. Doing a Spike Lee joint, it was independent filmmaking. To take that experience and then to look at Black Panther, my process had to have evolved to be able to do these much more complicated, intricate costumes. I love that it represents that. It’s more than just making a decision like, “Oh, Radio Raheem will wear a painted T-shirt.”

Bill Nunn as Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing (1989). Photo: Alamy Stock Photo.

It’s remarkable how much is in the exhibition, how much you’ve collected over the decades.

I’m a theater girl at heart. And in theater, when you mount a piece, after you create these beautiful costumes from scratch, you save them. When I got into film, I was thinking what is going to happen to these costumes now. Where are they going to go? Are we going to break everything down and go back to our lives?

So, I started collecting and saving them because people were gonna donate them to churches and I was like, “What’s the church gonna do with it?” I just couldn’t see them disappear. Anytime I could save something from a production, I did.

What other adjustments did you have to make when you transitioned from the theater to film and TV?

It was a huge adjustment because there is an aesthetic distance in theater where from the stage to the audience, a lot is lost. So, the composition is more important and color theory is more important because the audience feels it. It’s wonderful to experience how a play impacts the journey that the audience is going on because you can really wow the crowd, whether it’s with a fast change in the wings or how beautiful the composition is onstage. I was enthralled by that.

But when you get into moviemaking, nothing is filmed in order. Everything has a different look when you’re looking at it with the naked eye as opposed to how the film stock is going to affect it. That was a big learning curve. So, when I look back and I see whites that might pop a little bit too much, or zoot suits that might be too loud, I feel like it’s a reflection of my theater training. I’ve embraced those film mistakes, if you want to call them that, as coming from a good place, from a theater person.

Installation view of “Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design” at SCAD Fash, the Museum of Fashion + Film. Photo courtesy of SCAD.

In addition to Spike Lee joints, you’ve gravitated to projects that center the African American experience over your career. How do you see your participation in these productions?

I feel like as a designer, I can do anything if you give me time to research it. However, the African American experience, I live every day. And because I have this history of doing research on our culture and our history, I see it more when I go from city to city and coast to coast. I see our history laid out in front of me. I actually feel when people come into my fitting room, I can see their Ethiopian background or their Nigerian self. So, when I get the opportunity to delve deeper and go back in time to tell a period story or be inspired by images of what the African diaspora has to offer—why we love to sag our pants, why our hair is wrapped—it makes a connection for me. I’m all excited and ready to show the world why.

A still from Wakanda Forever. ©Disney

It’s a nuanced effort to showcase that diversity in the community without being stereotypical, which you definitely did in Black Panther. Your research for that project is legendary. Did you have a sense of how monumental that film was going to be?

I think so. Honestly, it’s like when we started Malcolm X. We knew it was important, but we didn’t know how monumental it was going to be received. But we knew how monumental it was in terms of the need in the culture to present our African ancestry. Within this superhero model, there were so many Marvel and Black Panther fans who were campaigning or waiting to see this film be produced. There was a fan base that was going to rejoice when the film was made. And since we were the ones doing it, we had a responsibility to make sure to extrapolate a rich story about Africa and Afro-future.

Every meeting I went to it, I had encyclopedic references. I had tribal books, I had picture essays, I had research and images. Every meeting, I rolled in there with a whole case. And the opportunity that that was lent to me and the rest of us—Ryan Coogler, Hannah Buechler, Rachel Morrison—was an incredible journey already.

Detail of a costume worn by the Dora Milaje in Black Panther (2018), designed by Ruth E. Carter. Photo courtesy of SCAD.

To you, what is a costume that works, whether on film or in the theater?

I think one stays connected to the performance, that allows the performer to feel like he or she is supported. There are some productions that I’ve shied away from because they had ensemble casts where I knew there would be competition amongst young actors. When you come to my fitting room, I really want to explore your character and how best we could tell their story as opposed to what would look great on you. I do want it to look great on you, but for more reasons than one.

Do you remember watching a movie or TV show or a theatrical production, picking up on the costumes for the first time, and realizing, “oh, this is a thing that needs to be designed?”

Yes, I would say Mary Poppins. I’m dating myself, but I remember going to see Mary Poppins and how she had that long coat and she had a whole look. As a young adult, my mom would also take me on bus trips to Broadway to see plays. So, I saw Mama, I Want to Sing! and I saw For Colored Girls. I was seeing these powerful costumes and dance performances that really impacted me.

Installation view of “Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design” at SCAD Fash, the Museum of Fashion + Film. Photo courtesy of SCAD.

Speaking of your earlier years, you also saved your childhood sewing machine, which is included in the show. What does it mean to your design journey? Did you sew?

I never actually got into it because I thought I was going to be a fashion designer. However, I was so intrigued that there was this machine in my room with booklets and patterns in the drawers. So, I taught myself how to sew and I loved the process. But the sewing machine was just there in my room and I was doing my drawings on it because I thought it was a desk. I guess my mother was just like, “This is great for my daughter.” It’s an old machine, too. I hope when people see it, they don’t think that I was born in the 1940s!

But it’s still part of my story and my mother’s story. I never asked my mother who gave it to her. But you know, the sewing machine in Black households is as commonplace as the iron. We have a legacy of seamstresses and cutters—we made the clothes. We weren’t going to the store and buying clothes for our children—we made the clothes. It’s a beautiful emblem of survival, our own form of technology. It was our Afro-future.

“Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design” is on view at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, 315 E Warren Ave, Detroit, Michigan, through March 31.