Law & Politics

As Part of a $4.5 Billion Oxycontin Settlement, the Sackler Family Has Promised Not to Lend Its Name to Museums for Nine Years

Critics say the agreement between prosecutors and the Sackler family doesn't go far enough.

Critics say the agreement between prosecutors and the Sackler family doesn't go far enough.

Sarah Cascone &

Eileen Kinsella

The highly contested Purdue Pharma settlement over the prescription painkiller OxyContin is one step closer to being finalized, as 15 states have dropped their opposition to the company’s bankruptcy restructuring plan.

In return, the pharmaceuticals giant has agreed to release millions of documents, and the Sackler family, who own the company, will contribute an additional $50 million to a $4.5 billion settlement fund set to be paid out over the next nine years.

Critics who hoped to see the Sackler family more severely penalized for their role in the nation’s devastating opioid crisis—which killed more than 500,000 Americans in the past 20 years—say the settlement still falls far short of real justice.

“The settlement is pretty appalling,” artist Nan Goldin, head of the advocacy organization Sackler P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now), told Artnet News. “The only thing that is an improvement is that they are going to be releasing millions more documents, even ones that fall under lawyer–client privilege.”

The settlement precludes future civil suits against some 1,000 individuals, including Sackler family members and associates. (Criminal prosecution is possible, but unlikely.)

The artist and activist Nan Goldin, who has been campaigning against the Sackler family. Photo by Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images.

“It’s just such an egregious abuse of our court system—but it’s also a court system that’s designed for the rich,” P.A.I.N.’s Megan Kapler added.

“[While] this deal is not perfect, we are delivering $4.5 billion into communities ravaged by opioids on an accelerated timetable and it gets one of the nation’s most harmful drug dealers out of the opioid business, once and for all,” New York state attorney general Letitia James said in a statement.

“While no amount of money will ever compensate for the thousands who lost their lives or became addicted to opioids across our state or provide solace to the countless families torn apart by this crisis, these funds will be used to prevent any future devastation,” she added.

“This resolution to the mediation is an important step toward providing substantial resources for people and communities in need. The Sackler family hopes these funds will help achieve that goal,” said the Sackler family in a statement emailed to Artnet News.

For cultural institutions, another big question remains: what exactly will their ties to the Sackler name look like now?

Previously, 23 states including New York and Massachusetts, had rejected Purdue’s plan, with their attorneys general issuing a joint statement in March decrying the settlement’s lack of accountability for the Sacklers.

The states had been pushing to include a provision in the settlement protecting nonprofits that have naming agreements with the Sacklers should they choose to remove the family name from their institutions. Such a concession is notably absent from the settlement as it now stands. Instead, the family will be prohibited from requesting or permitting any new naming rights in connection with charitable donations for the next nine years.

Nan Goldin speaking at the protest at the Met last summer. Photo: Michael Quinn.

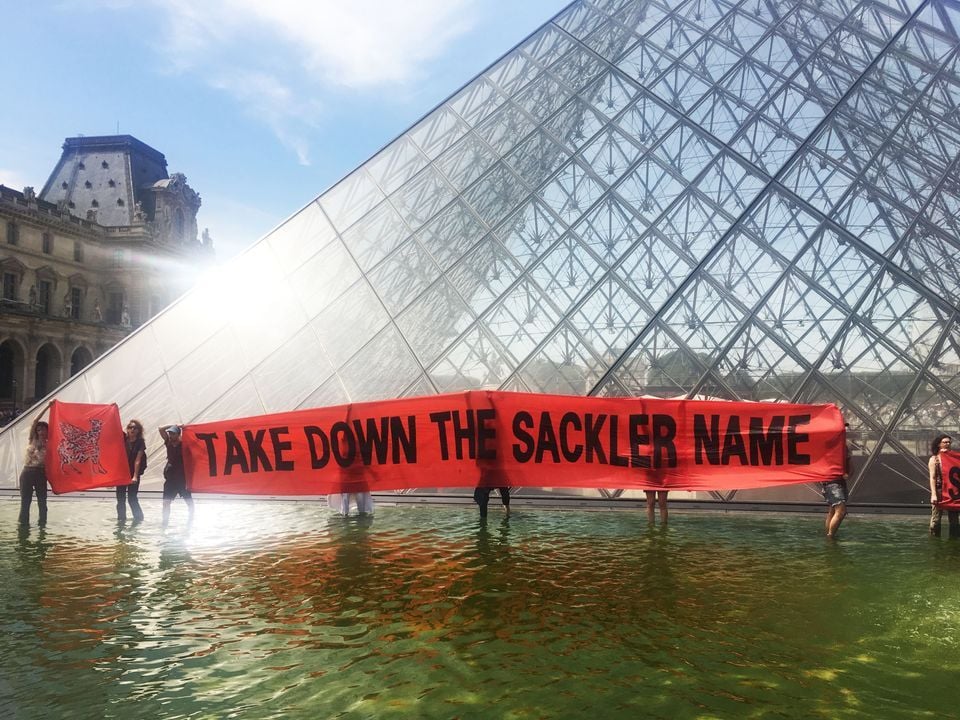

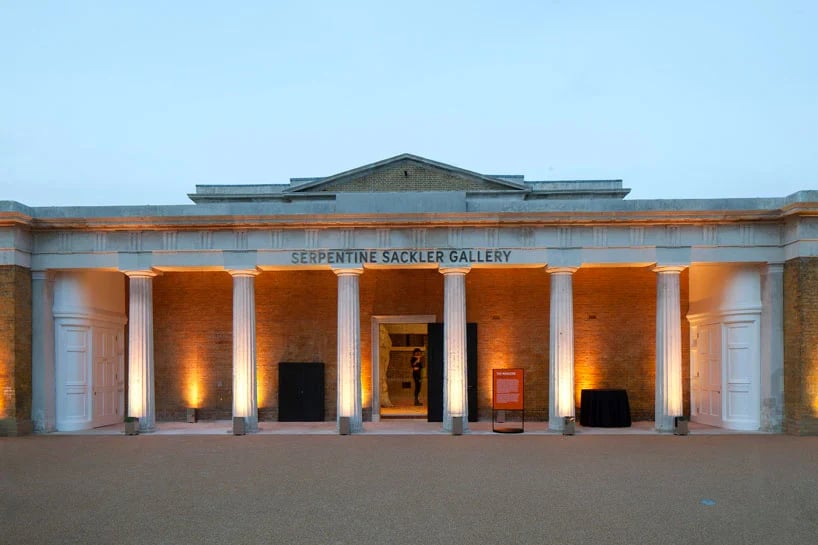

Some institutions have deemphasized the Sackler name, which is no longer mentioned on the website for London’s Serpentine Galleries, but still appears on the facade of what’s now referred to online as the Serpentine North Gallery.

But renaming physical spaces outright has proved more challenging. New York is home to the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics and the Sackler Educational Laboratory at the American Museum of Natural History; the Sackler Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and the Sackler Center for Arts Education at the Guggenheim.

London has the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Rooms at the British Museum; the Sackler Courtyard at the Victoria & Albert Museum; the Sackler Elevator at the Tate Modern; and the Sackler Room at the National Gallery; while the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s directorship is endowed in the Sackler name. There is also a Sackler Staircase at the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

(Other institutions are named after members of the Sackler family who did not profit from the sale of OxyContin, such as the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum and the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C.)

Many institutions have declined gifts from the Sackler family in recent years, including the National Portrait Gallery, the South London Gallery, and the Tate Modern in London; the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; and the Jewish Museum in Berlin.

The Serpentine Sackler at its opening in 2013. Photo ©Luke Hayes, courtesy of the Serpentine Galleries.

Most of the museums with naming agreements with the Mortimer and Raymond Sackler branches of the family tree have previously said they were not considering removing the Sackler name, but the Met has been reviewing the matter since October. (Arthur Sackler died in 1987, and his brothers Mortimer and Raymond Sackler purchased his one-third share in Purdue Pharma. OxyContin didn’t come to market until eight years later.)

“We are watching the development of this case very closely, and once we know what has actually been decided, we will take appropriate action to further the museum’s mission,“ a Met spokesperson told Artnet News in an email.

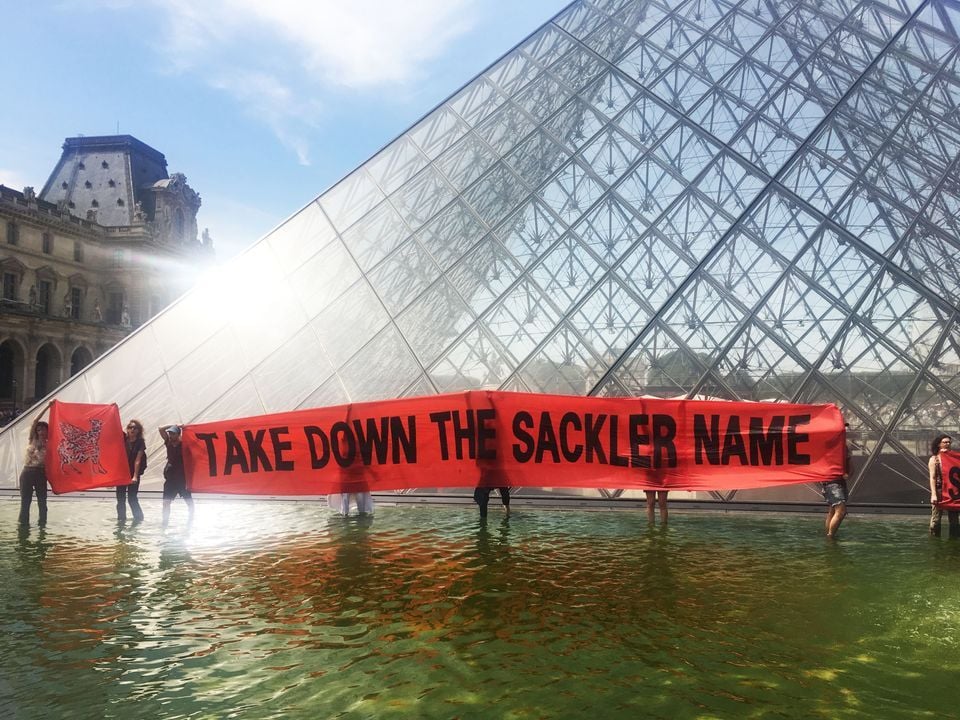

Other institutions declined to comment on the latest settlement news, and only six have officially removed the Sackler name to date: the Louvre in Paris, New York’s Dia Art Foundation, New York University’s Langone Medical Center, Edinburgh University, the University of Glasgow, and Tufts University in Boston.

The Sackler Family Trust did not respond to inquiries from Artnet News about whether it will renege on promised gifts or void existing gifts to institutions who choose to drop its name.

But its reaction to Tufts University’s removal of the family name from its medical education center this past December suggests there may be problems ahead.

An attorney for the trust sent a letter to the president of Tufts asserted that removing the name ran “contrary to basic notions of fairness” and constituted “a breach of the many binding commitments made by the university dating back to 1980 in order to secure the family’s support, including millions of dollars in donations for facilities and critical medical research,” according to the New York Times.

“Some members of the Sackler family opposed the removal of the Sackler name from our medical education building and programs,” a university spokesperson told Artnet News. “We have discussed our position with the family’s legal representatives and continue to stand by the decision.”

New York State Attorney General Letitia James announces the filing of the nation’s most extensive lawsuit against the manufacturers, Sackler Family, and distributors of opioids for their role in the opioid epidemic. Photo by TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP/Getty Images.

As part of the settlement, Purdue as a company will cease to exist. It will re-emerge as a new corporation that will put some of its profits toward opioid abatement, producing limited quantities of OxyContin and overdose reversal drugs.

According to settlement documents, the Sackler families will have no role in the selection of the new company’s managers or any other aspect of its governance or operations.

The Sacklers will also relinquish control of family foundations—which hold an estimated $175 million in assets—to the trustees of a National Opioid Abatement Trust.

The settlement also provides just $700 million to fill some 135,000 personal injury claims, leaving some claimants as little as $3,500. Payments will only be made to those who had prescriptions, not those who obtained Oxycontin from friends or off the streets.

P.A.I.N. is now planning a renewed series of onsite protests, focusing on pressuring the Met and the Guggenheim to renounce the Sacklers and remove their name.

“We hope that the museums will stand up and do the right thing,” Goldin said. “When everything else has failed us—the courts, the Congress, all our elected officials—we need to have faith in our museums and universities.”

“This is the end,” Patrick Radden Keefe, author of the best-selling book Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, wrote on Twitter. “It was always going to end this way—truth but not justice, some [money] but not enough, no real accountability to speak of.”