In 1967, designer Yves Saint Laurent met his match in Betty Catroux, a young émigré from Brazil who was then half-heartedly working as a model for Coco Chanel in Paris.

The two met for the first time at Chez Régine, a popular club that played host to everyone from playboys to princes. A grandfather of sorts to Studio 54, Chez Régine was the first modern iteration of a discotheque, and regularly turned out celebrities and cultural icons like Andy Warhol, Serge Gainsbourg, Jane Birkin, and Vogue editrix Diana Vreeland. As the English journalist Robin Leach once said of Paris’s social scene in the 1960s: “You’d just go to Régine’s every night and wait for the princesses to file in.”

Betty Catroux in her Paris apartment with her whippet. Photo by Horst P. Horst/Conde Nast via Getty Images.

Laurent and Catroux drowned their shared melancholies in nightly revelries and became fast friends. For Laurent, who was working to develop a new aesthetic he called the “masculine/feminine,” their relationship was a professional boon as well: in mens’ blazers and boyish clothes, Catroux instantly became what the designer called “the embodiment of the feminine ideal.” Her style laid the foundation for YSL’s slick, strong designs, which appealed to women who found themselves “in a seductive position when dressed in boy’s clothes,” as Catroux put it.

“She’s perfect in my clothes,” the designer wrote of the six-foot-tall Catroux. “Long, long, long.”

A splashy exhibition about the woman behind Saint Laurent’s pathbreaking work (“Betty Catroux: Feminine Singular”) opened at the Musee Yves Saint Laurent in Paris in early March. And though it remains off view to the public at the moment, there is still plenty to look at online. (The show is organized by Anthony Vaccarello, the house’s creative director.)

Yves Saint Laurent at his London store on New Bond Street with Louise de La Falaise (left) and Betty Catroux (right) in 1969. Photo by Dorean Spooner/Mirrorpix/Getty Images.

The exhibition illustrates how many of Saint Laurent’s pieces—from the safari jacket to the trench coat, to YSL’s iconic women’s tuxedo—were made to appease Betty, and how she helped the designer crystallize the mission of his couture house.

Catroux hated fashion. But her soft spot for her “twin” brother, as she called Saint Laurent, allowed her to continue to work alongside him for decades.

“For Yves, it was love at first sight, physically,” she tells Artnet News of their first meeting. “I was androgynous, asexual. It definitely affected him, but our resemblance was not only physical. We were alike morally, mentally. It was something incredible, and what was amazing about him was that he felt that I could be his soul mate—a kindred spirit.”

Yves Saint Laurent, Pierre Berger, and Andy Warhol at a party in 1977 in Paris. Photo by Michel Dufour/WireImage.

The pair shared an interest in art and artists of their era. Warhol, for example, who portrayed the designer in multiple works, became a close friend of theirs, and introduced them to the other artists he palled around with. Catroux has especially fond memories of their time at Le Sept nightclub.

“I met Francis Bacon there, whom I worshipped—he was lying dead drunk on a table—along with David Hockney and Robert Mapplethorpe, who was a great friend of [Saint Laurent muse] Loulou [de la Falaise]. Andy was there, obviously. When we got bored during a meal, we’d go downstairs to dance, flirt, and drink. And when we got tired of that, we went back to the table.”

Although she only met Hockney a few times, Catroux notes that he’s long been her favorite artist. “I find him fascinating as a character,” she says. “I have a passion for his work, which has a sort of childish and spontaneous side.”

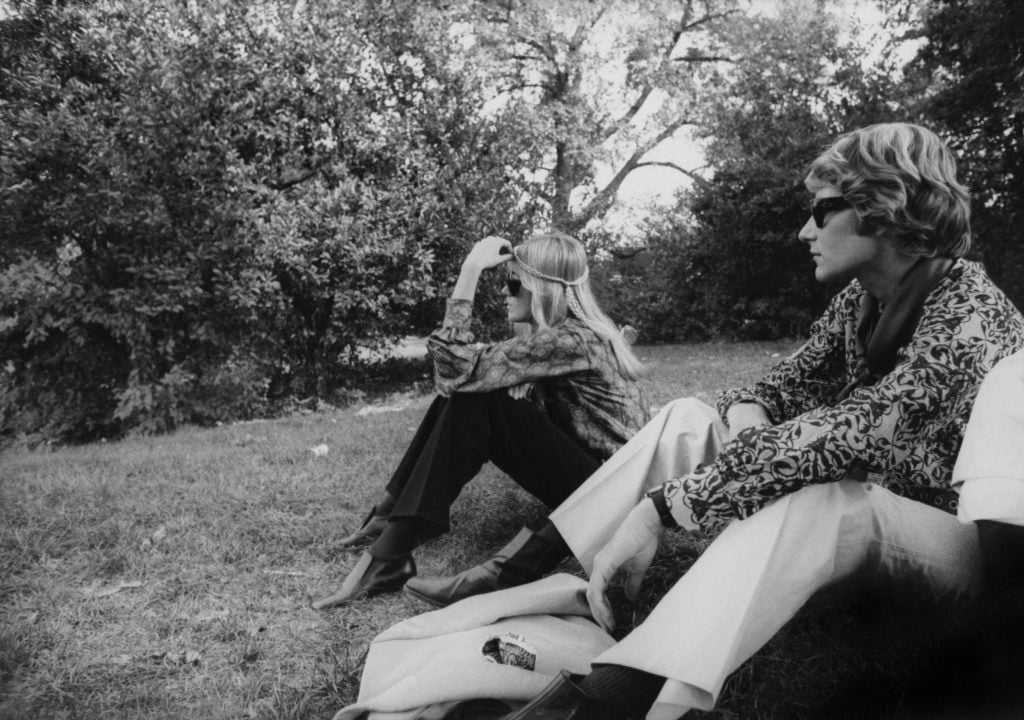

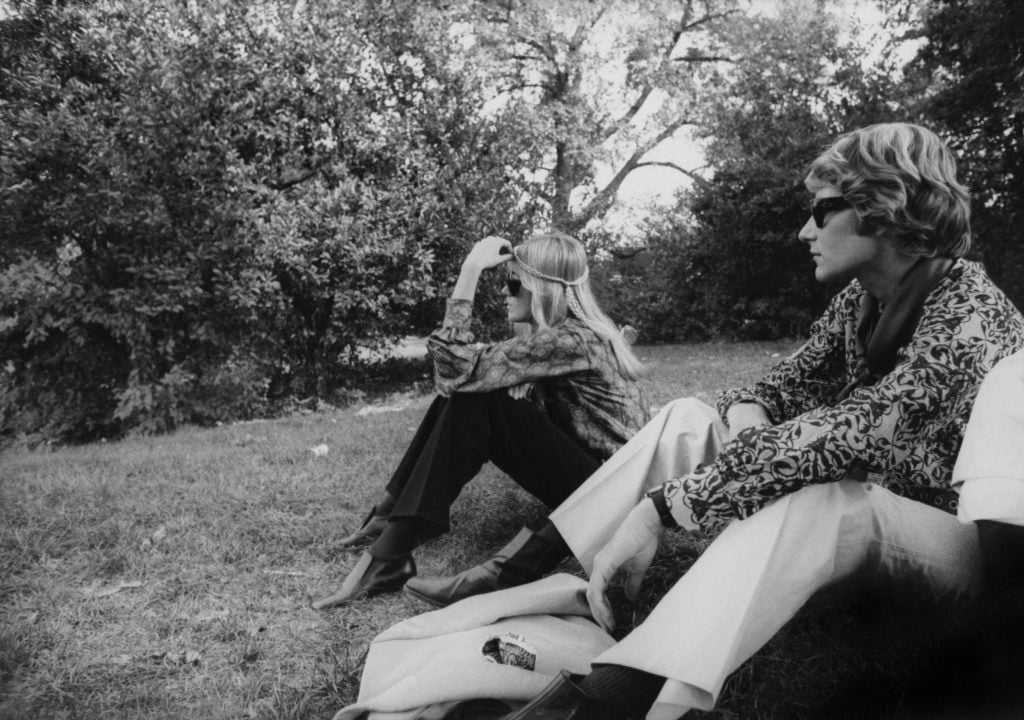

Saint Laurent and Betty Catroux sitting in Central Park in 1968. Photo courtesy Getty Images.

She recalls mingling with François-Xavier and Claude Lalanne, though they weren’t particularly close. Still, she says, it didn’t matter. Everyone lived for fun and continuously borrowed ideas from one another, spending days in each other’s ateliers and partying late into the night thereafter.

Since Saint Laurent’s death in 2008, Catroux has remained loyal to the brand he founded, showing up to fashion shows and modeling for the occasional campaign. “She lives and breathes Saint Laurent,” Vaccarello says.

One story captures that devotion especially well: each night, Betty Catroux raises a toast to an Yves Saint Laurent portrait made by Warhol.

“We lived for seduction,” Catroux says. “Seduction was our goal. To charm, to seduce; it gave us immense pleasure. As for the rest, it was all about partying, every night. To only do fun things. Be naughty. Drink. Excess. All the things that people don’t do anymore.”