Art World

A Previously Unknown Salvador Dalí Drawing Reveals the Surprising Methods Behind One of the Artist’s Most Famous Paintings

The artist's plans for his 'Last Supper' were more exacting than many realized.

The artist's plans for his 'Last Supper' were more exacting than many realized.

Brian Boucher

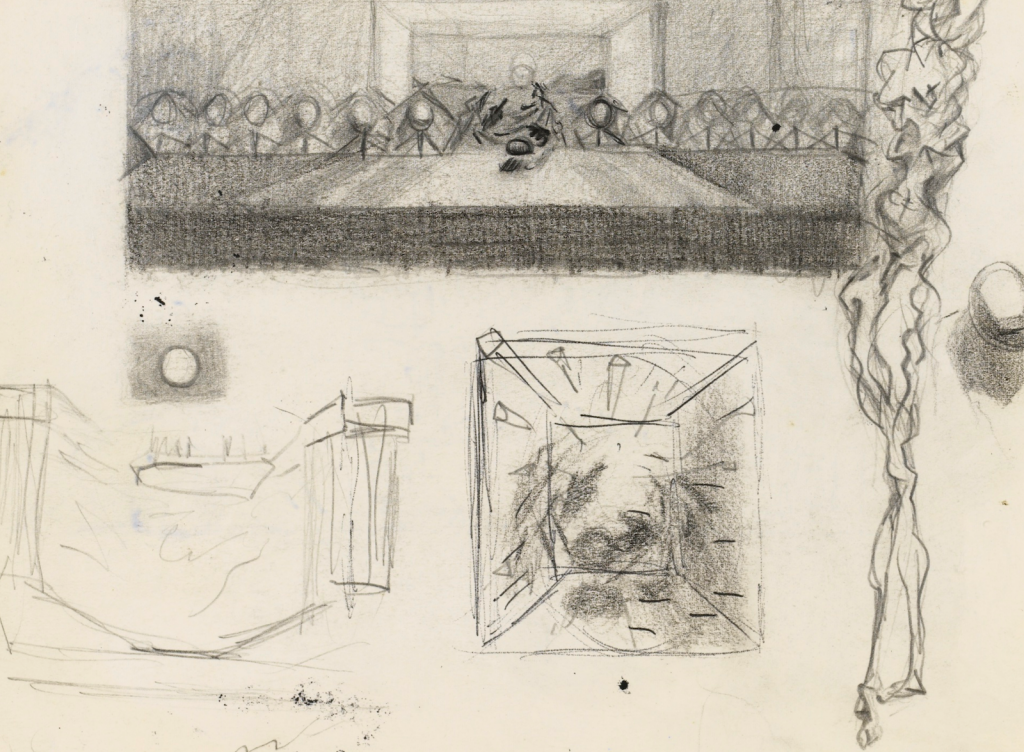

An unpublished Salvador Dalí drawing is giving new insight into one of the Surrealist’s most famous paintings, The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955), which is housed in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Collector Christopher Heath Brown, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, owns the drawing and has collaborated with art historian Jean-Pierre Isbouts, a professor at California’s Fielding Graduate University, to publish a book this spring with their research on the work.

One of the art historian’s goals, he told Artnet News, was to study the Surrealist artist’s indebtedness to the old masters.

“In terms of certain motifs, Dalí pays homage to Raphael, Velazquez, and Vermeer, but when it comes to execution, he very clearly channels the painstaking realism of the academic painters of the latter part of the 19th century in France, like Bouguereau and Meissonier,” he said.

In fact, the drawing is surprisingly exacting for Dalí. It has a top-down view in which the artist explored what that perspective would look like. The drawing is even conventional in its compositional style. But the artist was unconventional in following salon mainstays like Bouguereau, Isbouts pointed out.

“It’s important to realize that, in the 20th century, Bouguereau and Meissonier had lost every shred of credibility,” he said. “That began when realism became the enforced style of totalitarianism. It was simply verboten. Dalí discovered that if you put aside the fact that they liked to paint nude nymphs and other genteel pornography for the middle classes, they had simply incredible technique. The way they were able to model the figure was just stunning. And, in fact, Dalí actually had acquired a number of those paintings.”

Salvador Dalí, Study for the Sacrament of the Last Supper, 1954-55. Courtesy Jean-Pierre Isbouts.

The drawing is a preparatory sketch for Dalí’s Last Supper painting, and Isbouts describes it as an almost exact copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s rendition of the Last Supper. In the painting, on the other hand, Isbouts points out that Dalí departed from Leonardo’s frieze-like composition, with all the figures on one side of the table, and resorted to compositions previous artists had often used, in which the figures are more naturalistically oriented on all sides of the table.

“I can show you Byzantine mosaics that have an identical composition, with two of the apostles in front of the table, to give more depth. And he puts two on either side, which creates a more dynamic effect, and of course the geometric form, the dodecahedron, gives it more form,” said Isbouts. “He was very into sacred geometry at the time, and this also showed his sophistication and his technical ability to incorporate such a complex shape into a painting.”

Salvador Dalí, The Sacrament of the Last Supper, 1955. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Nearly nine feet wide and over five feet high, the painting doesn’t have the shock value of the artist’s earlier work, though there are surreal elements present. Christ’s body is partly transparent, and there is a ghostly torso looming above Jesus, its arms outspread, recalling a crucified figure. It also shows two apostles on the near side of the table with their backs to us, departing from the typical view, which has them all facing the picture plane.

Kirkus calls the duo’s book, titled The Dalí Legacy: How an Eccentric Genius Changed the Art World and Created a Lasting Legacy (Apollo), “a bright, accessible biography that connects the dots between Salvador Dalí’s surrealist masterpieces and their visual references.”