Art World

A Leading Old Masters Scholar Is Accusing London’s National Gallery of Unwittingly Inflating the Price of the ‘Salvator Mundi’

The claim ignited a flurry of letters and accusations among experts in the London Review of Books.

The claim ignited a flurry of letters and accusations among experts in the London Review of Books.

Naomi Rea

If you thought you’d heard the last of Leonardo’s contested final masterpiece Salvator Mundi, you have another thing coming.

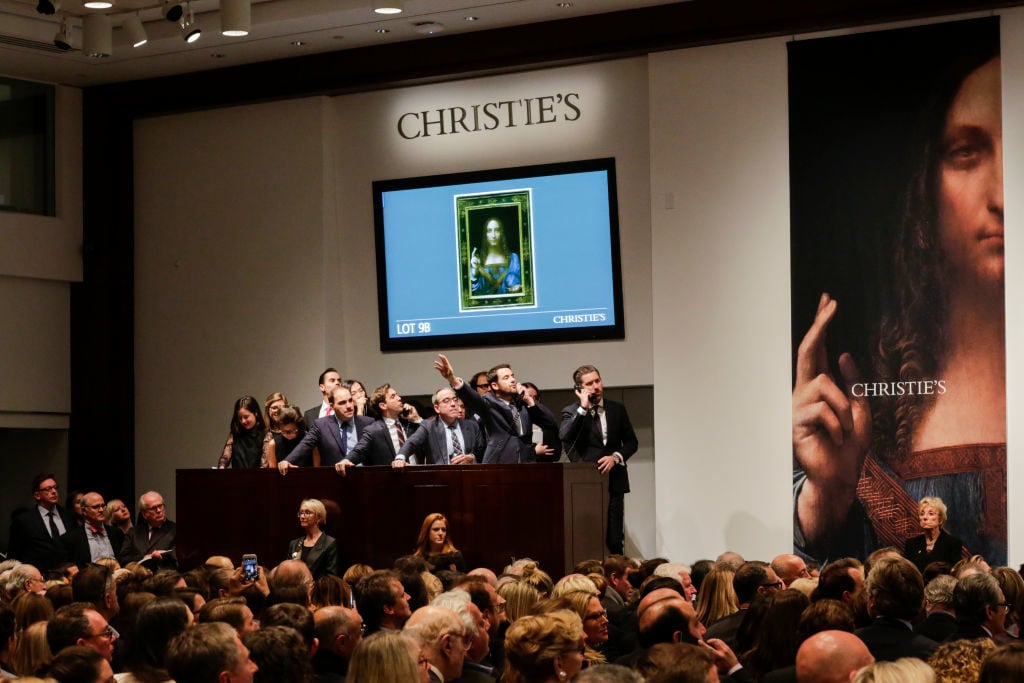

A leading art historian has accused London’s National Gallery of helping to inflate the price of the painting, which sold for $450.3 million at Christie’s in 2017, by exhibiting it as an autograph Leonardo without properly informing the public about the doubts surrounding its attribution. The historian, Charles Hope, argues in a recent London Review of Books article that the work’s presentation was particularly egregious given that it was available for sale both immediately before and after its inclusion in the show, “Leonardo da Vinci: Painter in the Court of Milan.”

In a flurry of spirited letters published in response to the article, two sides duke it out: Hope and fellow art historian Ben Lewis argue that the picture was effectively for sale during the exhibition—a somewhat unusual and frowned upon practice—while a former owner of the painting, dealer Robert Simon, and the former director of the National Gallery, Nicholas Penny, say it was not.

While the debate hinges on some rather technical issues, it boils down to one big question: Who gets to control the narrative about Old Masters (and Leonardo in particular): scholars or those with a vested financial interest in the work?

The now-infamous painting was originally purchased in 2005 by a consortium of collector-dealers for less than $10,000 when it was still thought to be a copy. The exhibition of the painting at the London gallery in 2011 was key to elevating its status as a genuine Leonardo before it went on to become the most expensive work of art ever sold at auction.

In an article published in the review’s January issue, Hope suggests the painting’s attribution was based on “misleading or unsubstantiated assertions about the provenance of the picture and a public statement by the then-owner.” He claims that Simon, who purchased the work in 2005 as part of a consortium, “exploited” the National Gallery into exhibiting the contested work as a Leonardo without properly qualifying it. He writes that in doing so, the publicly funded institution was participating more in “a marketing ploy than a contribution to knowledge.”

In a retort to Hope’s article, Robert Simon reiterates an earlier claim that the picture “was not” for sale at the time of the exhibition and that a press release he issued at the time responded to inaccuracies in the press in a “purely corrective, not promotional” manner. And in fact, he points out, the loan of Salvator Mundi to the exhibition was actually requested by the gallery, not the reverse. The National Gallery’s former director, Nicholas Penny, confirmed that account in a letter of his own.

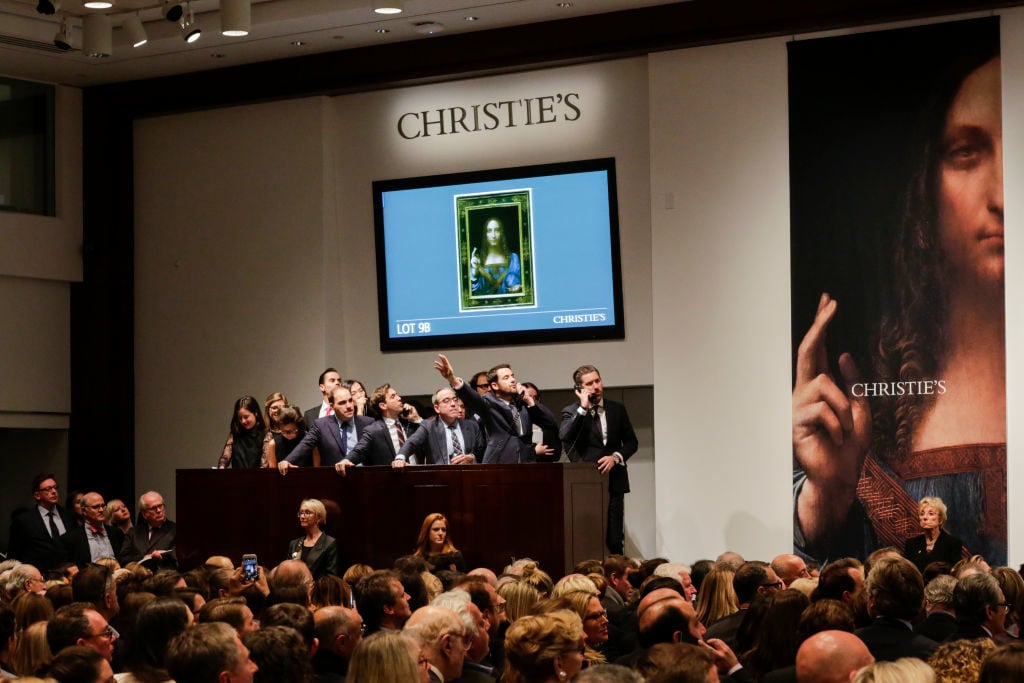

Christie’s employees pose in front of Salvator Mundi ahead of its sale at Christie’s New York on November 15, 2017. Photo: Tolga Akmena/AFP/Getty Images.

With that, the saga might have been over—but instead it took a fascinating turn when Ben Lewis, the author of a book on the painting titled The Last Leonardo, threw his hat into the ring. In his own response letter, Lewis calls Simon’s claim that the work was not for sale “disingenuous.”

He says that since the publication of his book, he has received “testimony” from an antiques dealer, Michael Franses, claiming that he had been working to sell Salvator Mundi on behalf of some of its co-owners in 2009 and 2010, just before it went on view in the National Gallery, and that Simon was “aware” of this. Franses, Lewis claims, even assembled dossiers about the painting’s provenance and condition and reached out to such museums as the Louvre, the Hermitage, the Vatican, Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie, the Qatar Museums Authority, as well as the Prado.

“The plan was to get a museum to agree to accept it as a Leonardo and then find wealthy donors who would pay for it for that museum,” Lewis writes. He goes on to suggest that “perhaps what Simon means is that he briefly took the Salvator Mundi off the market between July 2011 and February 2012 to avoid any embarrassment to the National Gallery.”

Since Lewis’s explosive claim, Simon has attempted to play down Franses’s involvement. He told the Guardian that Franses had “proposed to offer the painting to a single museum with which he claimed to have a special relationship,” but that he had been unaware of any conversations with other institutions. Simon acknowledged he shared some information about the painting with Franses, although he never met him.

Contacted by Artnet News, Simon doubled down on his position. “I can state absolutely, categorically, without any doubt, prevarication, or question, that the Salvator Mundi was not for sale, actually, effectively, or implicitly, at the time of the Leonardo exhibition at the National Gallery,” Simon said. Franses did not immediately return requests for further comment.

Contacted by Artnet News, a spokesman for the National Gallery said that during the period that Salvator Mundi was on display in the gallery, “the owners said that the painting was not presently for sale.” The spokesman explained that when the gallery considers a painting for a loan exhibition that is owned by a dealer or known to be for sale, it considers the benefit to the public and the contribution to scholarship of the exhibition, but that “the work should be included solely on its own merits.”