Up Next

Samantha Joy Groff Captures the Mystique and Mythology of the Rural ‘Huntress’

The Pennsylvania-based artist's recent paintings are on view in "Huntress" at Half Gallery in Los Angeles.

“A darkness lives right below the surface of the everyday and that darkness is like a live wire. Most of us have felt it, but some of us are haunted by it,” said artist Samantha Joy Groff in a phone call from her Pennsylvania home. “That feeling follows me through my days.”

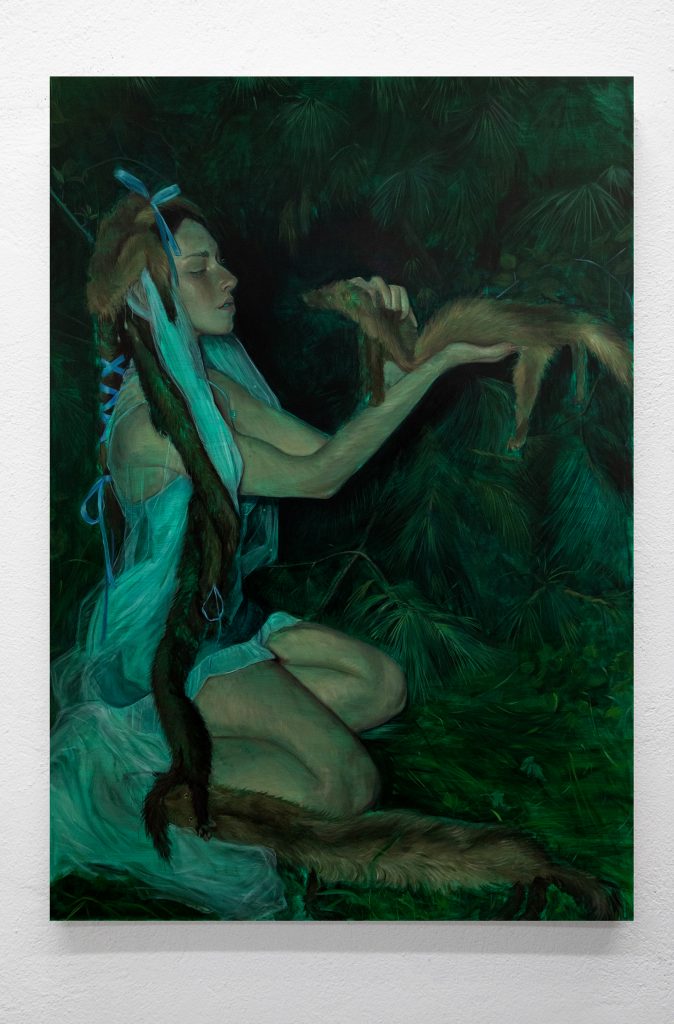

Groff’s newest paintings, a selection of which are on view in “Huntress,” a solo exhibition at Half Gallery in Los Angeles which opened coinciding with Frieze L.A. this week, picture young women, clad in satiny blue negligees, cavorting in forests under the dark of night. A supernatural force feels to be at work here. The women cradle mallards and caress deer. They contort their lithe bodies and their eyes loll, seemingly ecstatically. Groff, who was raised in a Mennonite community in rural Pennsylvania, refers to these works as “Dark Pasture Encounters”—a riff on “Freedom Encounters,” a contemporary exorcism ritual practiced by a niche of Christians.

Samantha Joy Groff, Huntress in Valor (2024). Courtesy of Half Gallery. Photograph by Sofia Colvin

Fascinated by the myths of Diana, goddess of the hunt, the moon, and chastity, Groff has evoked, in these paintings, a world in which women, rather than releasing supposed demons, revel in their ritual powers.

“The goddess Diana turned men into deer,” said Groff, alluding to the myth of Diana and Actaeon, “You’ll notice there are very few men in my universe—unless they’re animals.” In one painting, Lover’s Knot, two bucks lock antlers, perhaps a representation of the futility of male aggression or entwined passions. “Women are at the top of the hierarchy in my paintings. And while they aren’t villainous—they do indulge a kind of grotesqueness, adorning themselves with furs.”

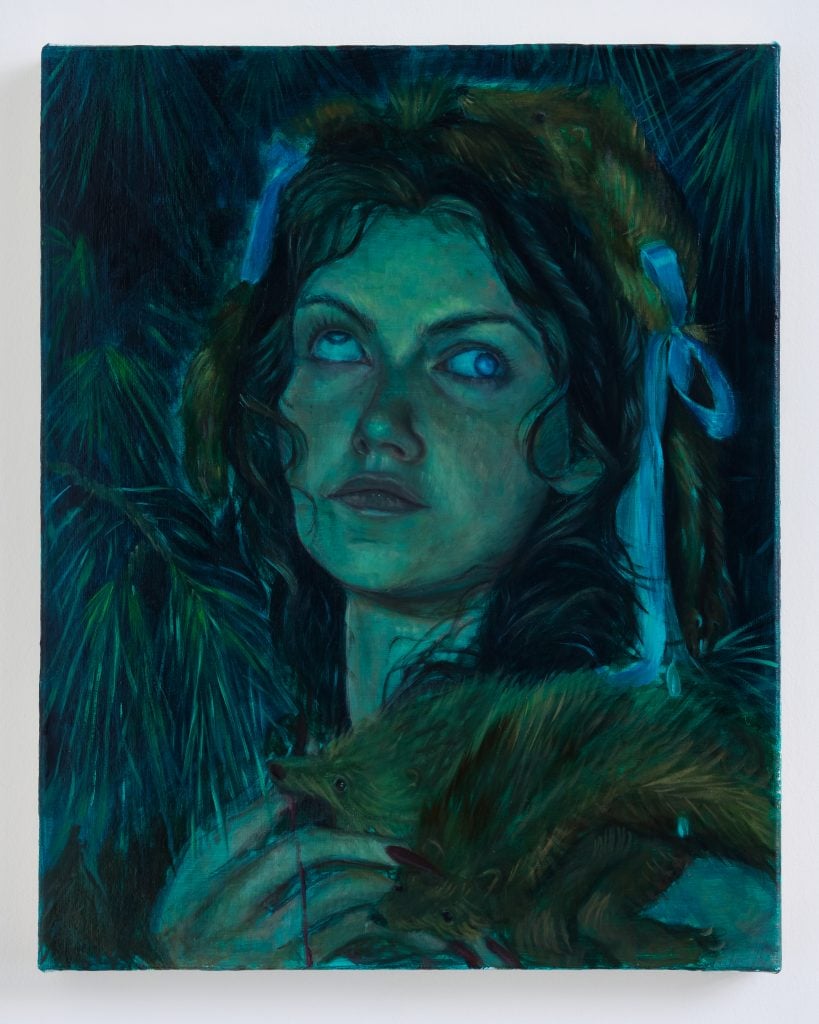

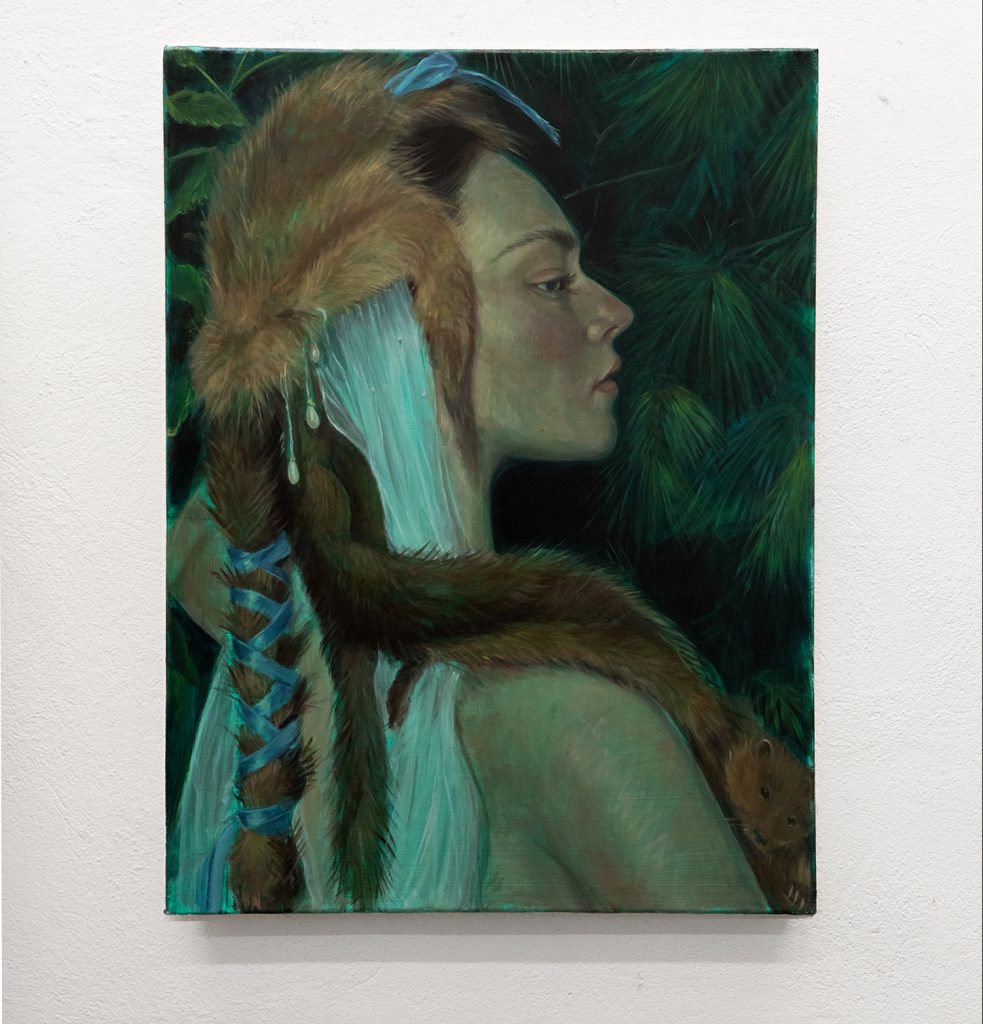

A headdress made of ferret pelts and pale blue ribbons appears in several canvases. Groff, who has a background in fashion and film, made the headdress by hand. For each of her paintings, she stages the tableaux in real life first, often using friends and family as models, whom she poses and costumes.

Samantha Joy Groff, Backwoods Diana the Huntress (2024). Courtesy of Half Gallery. Photograph by Sofia Colvin

“With this headdress, I was deeply influenced by Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady With an Ermine. It’s such an interesting choice of animals to symbolize chastity,” Groff explained, “I had been already working with taxidermy and one step further felt like creating this new pseudo-religious garment.”

Hunting was at the forefront of her mind as Groff made the paintings. The artist considered the contradictions between luxurious art historical depictions of the chase and the everyday realities of the rural American version. “’What does hunting look like to me, today?’ I wondered. And not so on the nose as depictions of carcasses and people holding up a rack for a photo,” she explained “I wanted the women to become the hunters.”

Installation view “Huntress” 2024. Courtesy of Half Gallery, Los Angeles.

Groff’s entwined relationships with the people of Southeastern Pennsylvania, particularly the women in these communities, form the backbone of her practice. “These girls are people that I know or grew up with. In the past, I’ve used my family as models, and they’ll arrive in clothes they made themselves and have their hair covered,” she explained. “Endurance—the endurance of these girls—is part of the paintings. It will be 30 degrees outside and they’ll be in these little outfits and they’re letting me push them—pose them—in a way that takes a lot of trust,” she said with a laugh, “When I’m saying, ‘Hey, I’m going to pick you up at midnight and we’re going to drive to my uncle’s creekbed and I’m going to have all these weird dead animals in my car!’—there’s trust involved.”

Often Groff will sketch out an idea of how she wants bodies positioned for her paintings, but the realities of the elements and the physical limits of each woman’s body will often force her to reimagine a composition on sight. Staging these compositions in wooded areas, late at night, she lights the scenes with her car’s high beams and photographs the women, using the photographs as guides back in her studio. The process is laborious but intentional. “Where I’m from, you spend a lot of time driving at night. Anytime you drive on a backroad, headlights are what’s pushing you through this dark world of these hidden things—capturing that element is important,” she said.

Samantha Joy Groff, Soul Purgation (ascending, illuminated) 2024. Courtesy of Nicodim Gallery.

Groff, who earned her MFA at Yale in 2022, had previously earned a BFA in Integrated Design, from Parsons and a Bachelors in Film Studies from New School. These studies have shaped elements of her process. “I got a late start as a painter. I’m only the second person in my family to go to college,” she explained. “I studied design. I wasn’t very good at it. So, I was always painting on the side. But I would make films whenever I had the chance back in Pennsylvania—always with elaborate costuming. I called the costumes ‘sacred garments’ and I would take clothing or items my grandmother or aunts had crafted and hand sewn and turn them into my own weird performance garments.”

Since graduating, Groff has had a rapidly rising art world profile. In 2022, she made her solo debut with Martha’s Contemporary in Austin, Texas, which was soon followed by her Los Angeles solo exhibition “True Lies” at Nicodim Gallery. In 2023, she had her New York solo debut “Dark Pastures” at Half Gallery’s East Village space. This October, she will have a New York solo exhibition with Nicodim.

Samantha Joy Groff, Backwoods Penitent Diana, Prophetic (2024). Courtesy of Half Gallery.

Even within the past few years, Groff’s paintings and drawings have formally evolved. Earlier works often centered on depictions of women in Mennonite attire (these works call to mind the muscular religiosity of Gaugin’s Breton period). More recently, however, her approach is more oblique, delving into the mysteriousness of a community that extends beyond definable language.

“I always want to create a foreboding sense that something is about to happen in the painting or something just happened. The action is off-frame or happening just before or just after,” she explained.

In some ways, these recent paintings indirectly allude to traditions within the Pennsylvania Dutch and German communities. “Thinking of these paintings there’s a Christian practice called Brauche which is a healing prayer over animals. It’s strange—it’s not witchcraft but it has this otherworldly aspect. I guess you can say I’m working with elements of what I know. I think anyone who has grown up in a rural environment can understand this—it’s the question and unknown answer of what goes on in backwoods at night.”

For Groff, her paintings are meant as a homage to the women she grew up with. “My paintings are for girls who have felt less than, or dirty, or low,” she explained, “Anyone who has found freedom in those weird private moments that are like completely dissociated from reality, I am painting for them.”

Samantha Joy Groff, 2024. Courtesy of Half Gallery.