Phil Collins’s collection of relics related to the Battle of the Alamo is finally getting a dedicated museum—even as the authenticity of some of the objects remains in doubt.

Following nearly a decade of planning and construction, the $20 million, 24,000-square-foot venue dedicated to the rock star’s collection and other Alamo artifacts is set to open in San Antonio next year, according to the Art Newspaper. When it does, the historic plaza—home to the Spanish mission where the 1836 Battle of the Alamo took place—will finally have a modern educational facility fit for the roughly two-and-a-half million tourists that come to visit the historic site each year.

And yet, for those who have followed the—ahem—genesis of Collins’s museum, those details may come as a mild surprise. When the musician—and father of Emily in Paris actress Lily Collins—donated his 400-plus-piece collection to Texas in 2014, he did so through a contract stipulating that the state would build a four-story, 100,000-square-foot museum to house it. It was supposed to be completed by October of this year.

That larger institution is still in the works, despite an ongoing public dispute over the state’s use of $150 million in taxpayer money to finish the project. The planned museum is now tentatively scheduled to open in 2026.

Meanwhile, another controversy continues to loom over the prospective museum.

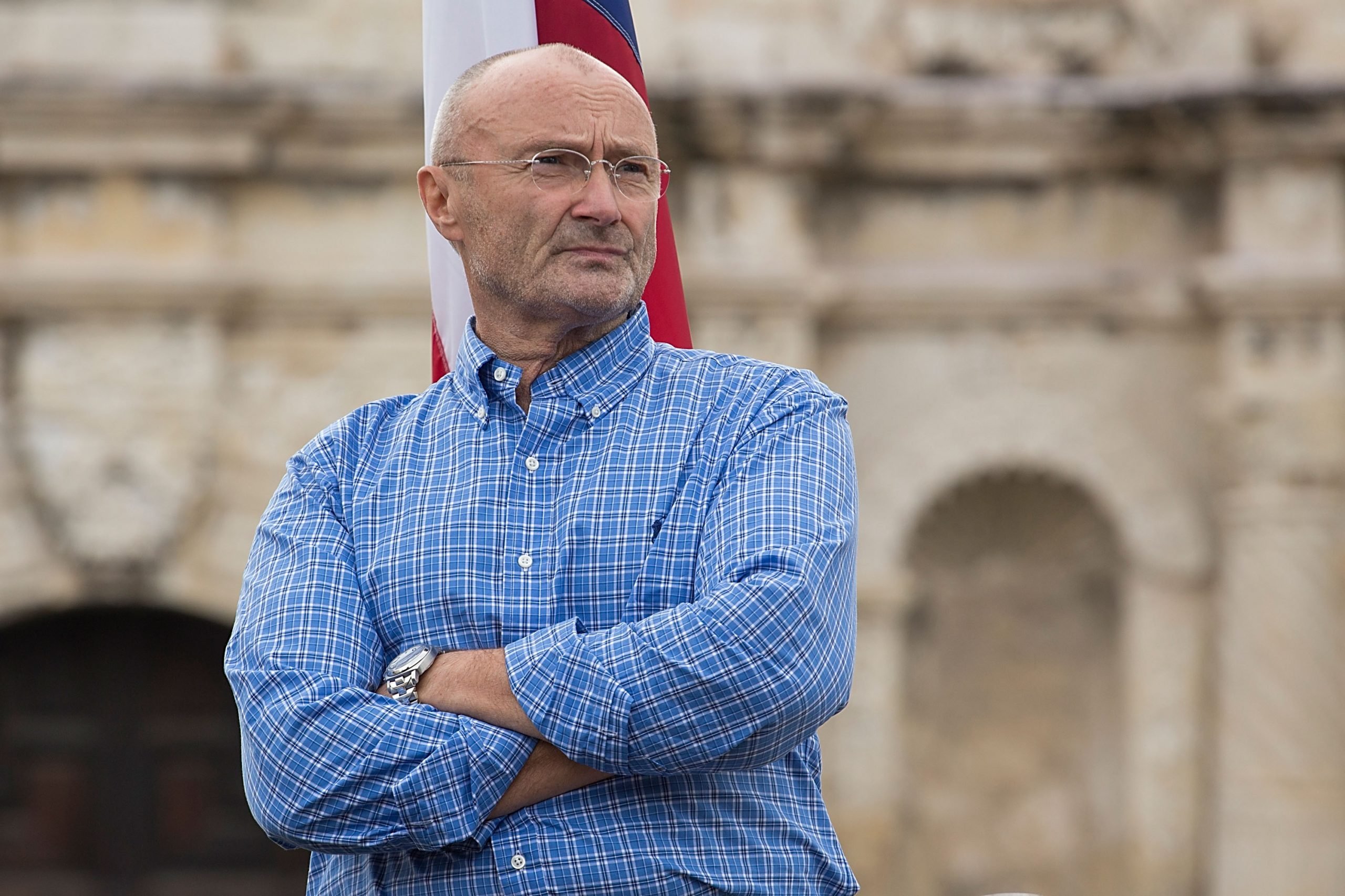

Phil Collins stands in front of The Alamo after announcing the donation of his collection of historical artifacts related to the site on June 26, 2014 in San Antonio, Texas. Photo: Gary Miller/Getty Images.

In a 2021 book called Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth, a trio of historians raised doubts about the authenticity of several pieces in Collins’s collection. Among the objects called into question are a shot pouch owned by Davy Crockett, and two knives—one owned by Jim Bowie, the other by William B. Travis.

The Bowie knife, for instance, lacks proper provenance documentation and is believed to have been authenticated by a psychic. It was acquired by Collins through two men, businessman Alexander McDuffie and historian Joseph Musso.

Last year, McDuffie and Musso jointly filed a defamation lawsuit against Forget the Alamo’s three authors; the title’s publisher, Penguin Random House; and Texas Monthly magazine, which had previously published excerpts from the book. The lawsuit argues that the publications contained “false statements, mischaracterizations, and significant omissions”.

Just 50 pieces from the Collins collection are expected to go on view during the museum’s opening next year; they’ll share exhibition space with objects from the Alamo Trust’s own collection, as well as Spanish colonial-era pieces donated by the philanthropists Donald and Louisa Yena.

But the number of Collins-owned items planned for display isn’t necessarily a reflection of the quality of his collection, according to Alamo senior curator Ernesto Rodriguez.

“Unfortunately, people are focusing on a couple of items and making the entire Collins collection seem invalid,” Rodriguez said in an interview with TAN. “The collection not only tells the story of the Texas Revolution but also about how people collect and the perils of collecting. He’s a wonderful individual who has been very generous to the Alamo and the people of Texas.”

The curator clarified that “there were a few items [with provenance issues],” but noted that those objects “will help us tell a different side of the Alamo story.”

“It’s about showing a story of how people collect,” he said. “Every object has a story to tell and that’s the important thing about a museum—that we tell a story honestly, whether it’s good or bad. We are focusing on telling the honest story of a collector’s journey.”

More Trending Stories:

This Creepy 17th-Century Baby Portrait Was Found in the Home of an ‘Eccentric’ English