Gallery Network

7 Questions for Artist Liu Jian on the Inspirations of Nietzsche and Pushing the Boundaries of Artistic Mediums

The artist's solo show "Daybreak" is currently on view at Santo Hall, Beijing.

The artist's solo show "Daybreak" is currently on view at Santo Hall, Beijing.

Artnet Gallery Network

Beijing-based gallery Santo Hall is presently showing a solo exhibition of work by artist Liu Jian, “Daybreak,” showcasing the artist’s recent body of work. Santo Hall first opened to the public in 2021 with the Tongli Space of Jindongtang, an independent art project space, and in 2023 opened a gallery in the 798 Art District, the 798 Space of Dongtang. Centrally located, the gallery expanded its scope and reach and showcases Chinese contemporary art, crafting a program that engages in dialogues around the current growth and evolution of cutting-edge art.

“Daybreak” and the platforming of Liu Jian speaks to the gallery’s core ethos of promoting art that interrogates the foundations of artmaking itself, with the artist both formally and compositionally exploring the boundaries between representational and abstract, and the limits of the medium.

Marking the occasion of his solo show, we reached out to Liu Jian to learn more about the inspiration behind this body of work, and what he’s working on next.

Artist Liu Jian. Courtesy of Santo Hall.

Can you tell us a bit about the body of work going on view in your solo exhibition at Santo Hall? What are some of the core themes or ideas underpinning the show?

This solo exhibition, “Daybreak,” is inspired by Nietzsche’s writings and aims to reassess and re-evaluate the value of painting. The exhibition presents a mini trilogy: “Memory, Rhapsody, and Wasteland,” corresponding to reality, stage, and post-humanity, respectively.

In these works, I attempted to develop a method similar to coding, which can release a sensorial experience through the movement of the material. The medium is untethered and can disperse or quickly concentrate in one area, and has the capacity to bind intertwining, volumetric form with space, or create images and spaces. It possesses a musical quality, but it differs from music; it is not a linear organization and can disrupt or halt the flow of time at any moment. In this view, time is a standard that humans find convenient to understand and quantify. In the occurrence of events, time implies the essence of movement. Movement lends a technical aspect to time, making events become temporary states that condense into my painting.

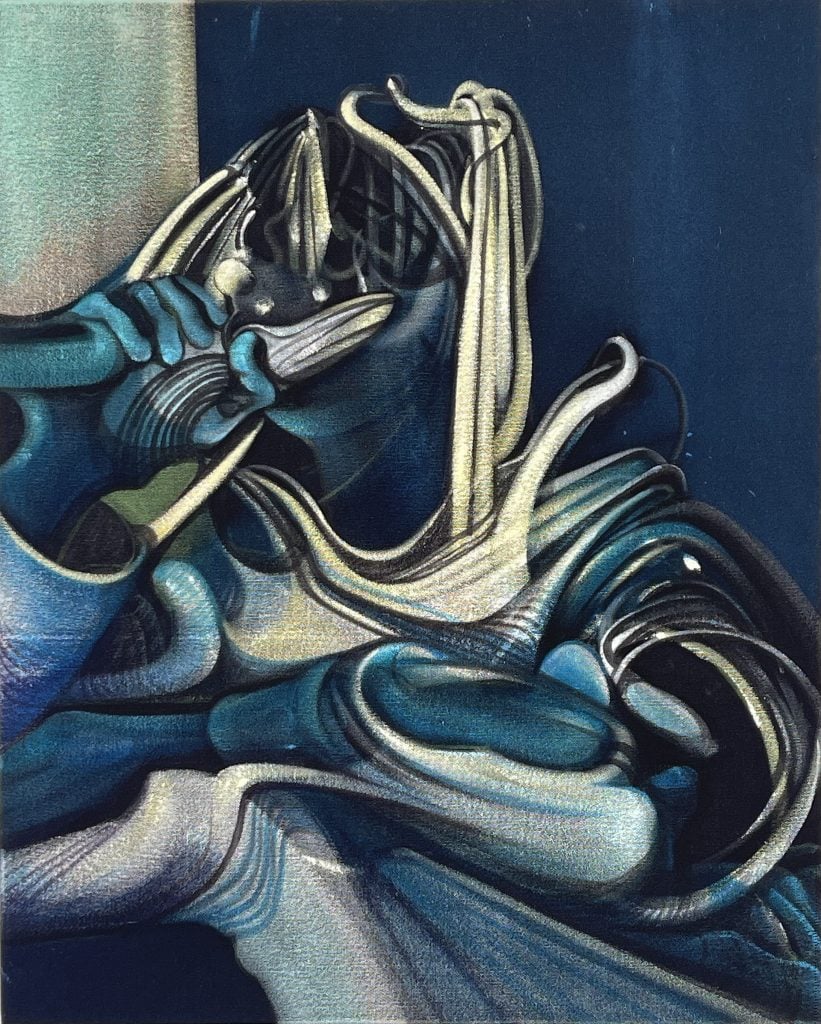

Liu Jian, The Whipmaster (2024). Courtesy of Santo Hall, Beijing.

How do the works in the show continue or diverge from works you’ve made previously in your career?

Around 2016, I often worked outdoors, creating large-scale paintings without stretching the canvas. The primary goal was to explore the intrinsic characteristics of various woven materials, essentially an exploration and presentation of materiality. I used methods like collage, dyeing, washing, and printing to explore the possibilities of technique. Engagement, fusion, and intervention allowed painting to become an independent object carrying special markers.

I often liken this to a librarian’s archival work—selection and judgment lead to new perceptions of my surroundings and a new understanding of my own boundaries. Recent paintings have transformed earlier work into a medium itself, acting as systematic tools and materials produced by me. My understanding of the material aspects of painting has remained largely unchanged, stemming from my interest in the murals of both Eastern and Western art. Whether in the area formed by saturation or the rough, matte surface, these elements have consistently appeared in my work.

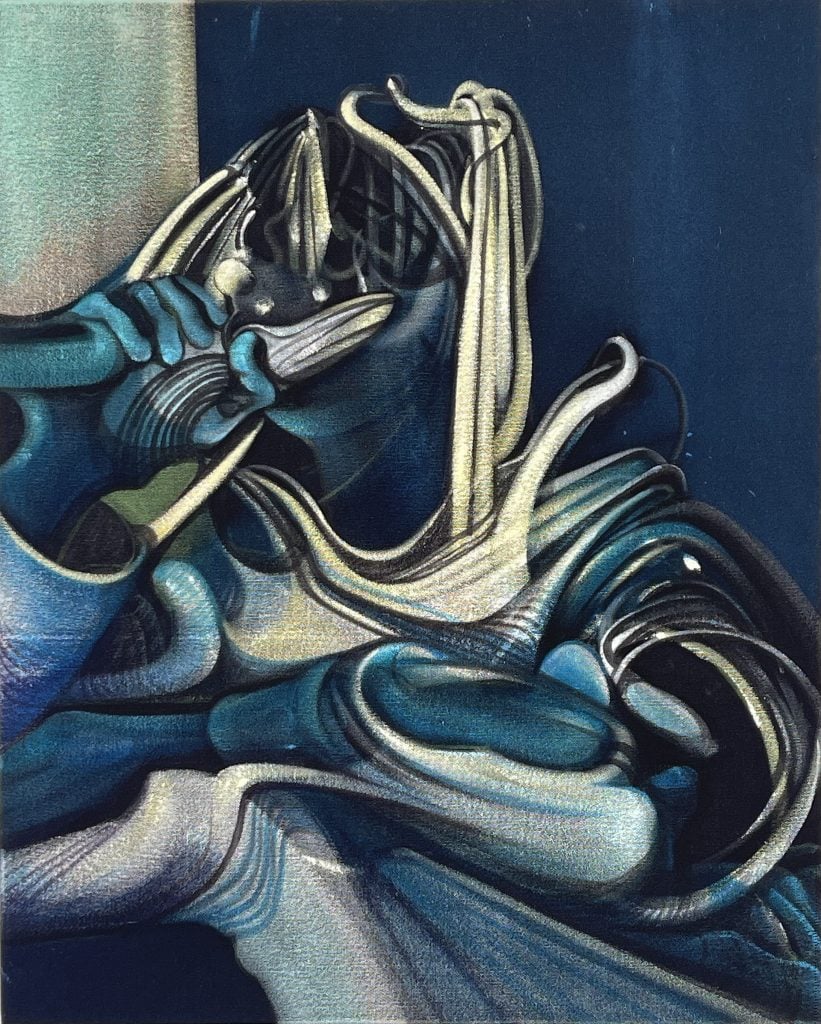

Liu Jian, Wasteland (2024). Courtesy of Santo Hall, Beijing.

What do you want the viewing experience to be like for visitors? What do you hope they take away with them?

I hope the audience can bring my work experiences that differ from my own, as these will impact my work. I also aspire to establish a more open channel for communication. I hope they take away something that can be reawakened in their experiences and lives through my paintings—something that inherently belongs to them. In conversations with curator Ms. Zhan Mo and some friends, I saw this possibility, which brought me comfort. One friend shared his emotional experiences during his school years, while another discussed the plot of a particular animation with me. These were unknowns that I hadn’t touched upon.

Over the course of your career, your work has undergone several evolutions, been described as “radical material explorations,” and notably you have been using black, unprimed canvas and oil paint. From a technical standpoint, how did you arrive at these materials?

Over approximately ten years of exploration, I have focused on the sensory response of woven materials, presenting extreme colors, and forming new material states. The components of color and pigment content directly affect the saturation of the image. My use of black unprimed canvas aims to further compress the depth of color, allowing for more possibilities of deep colors. This is similar to the technique of glazing in classical painting but differs in achieving a matte surface quality that brings the image closer to the qualities of Renaissance painting, while being entirely distinct, as it is realized on canvas. This practice has led me to discover new qualities through repeated refinement.

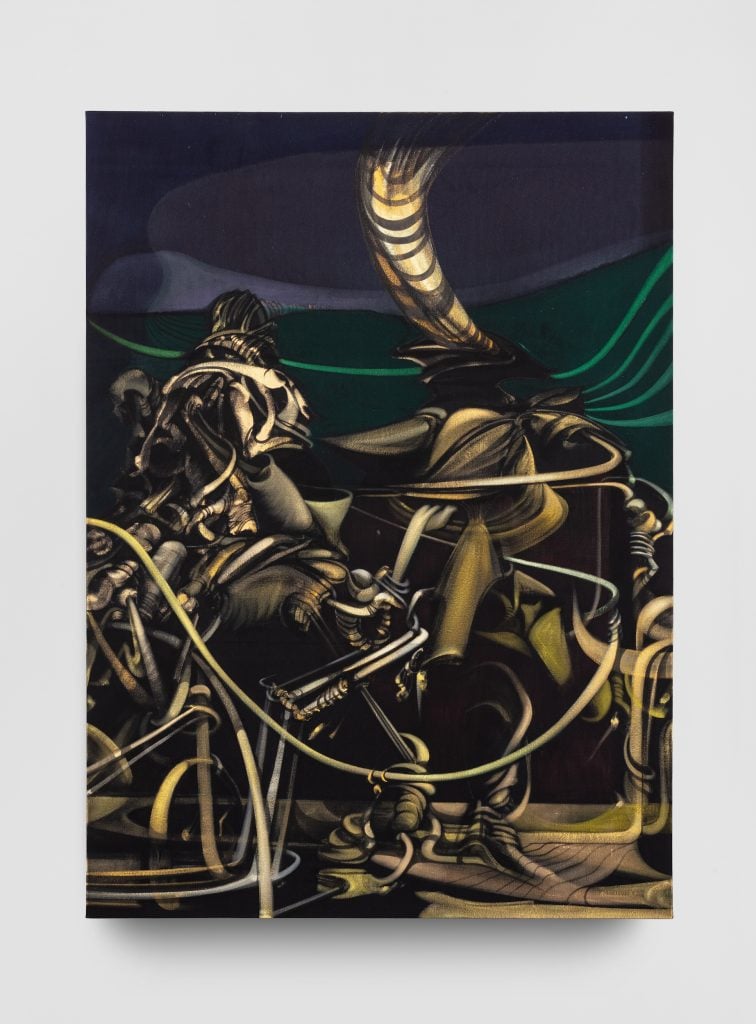

Liu Jian, Barbershop (2024). Courtesy of Santo Hall, Beijing.

How would you describe your creative process? Is it intuitive and process led, or do you plan everything out beforehand? Are you ever surprised when making a new work?

My painting generally begins with long-term observation of events occurring in real life, sourced from images on the Internet, photographs, and first-person accounts. Prolonged, repetitive observation hones a certain judgment and sensitivity towards the painting. For instance, I extract elements of painting from blurred images, attempting to guide new structures with these elements, layering transparent colors over large areas to allow them to permeate and overlap, creating a medium for a movable structure. Intervening in the image and manufacturing the medium can summarize my practice’s characteristics.

Intuition leads the way, but once the work begins, I set subjective limitations on its scope, establishing constraints as the foundation for potential generation. Deepening the details of the image and returning to the whole has always been my fundamental concern. New works surprise me as a re-examination of the construction and growth process, and sometimes as the allure of reassessing value during unexpected occurrences. Of course, I generally remain vigilant about this. Slowing down and rereading the image usually eliminates the feeling of surprise, allowing my sensitivity to return to a state of lasting restraint, helping me calmly face new challenges.

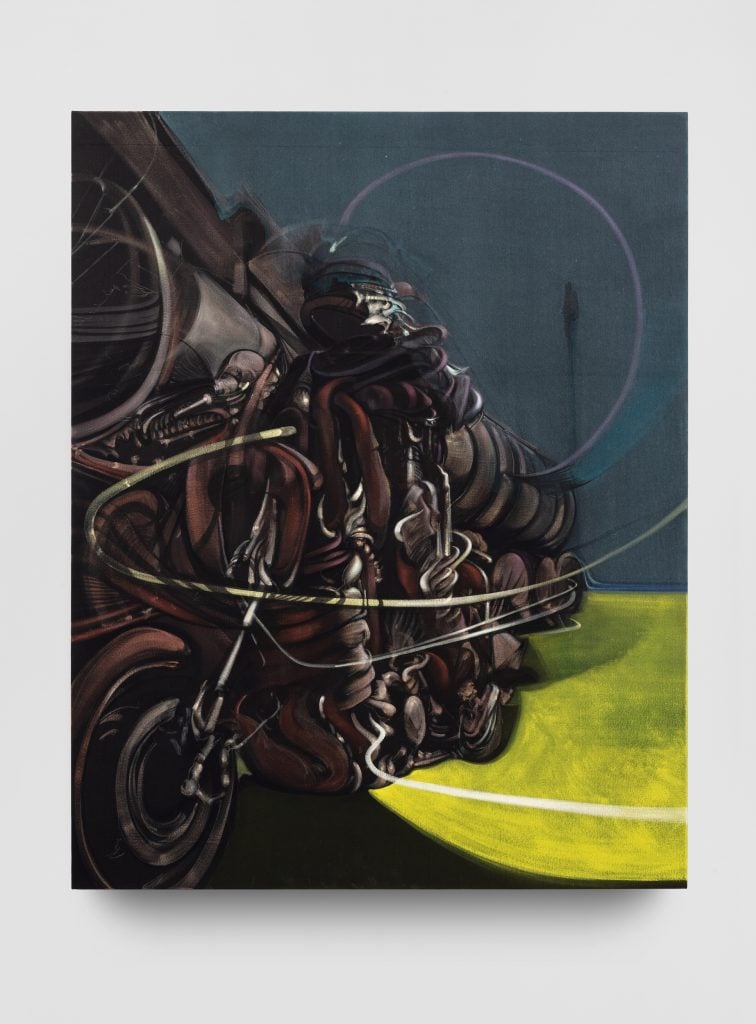

Liu Jian, Where To Go (2024). Courtesy of Santo Hall, Beijing.

Conceptually speaking, where do you most frequently look to or find inspiration? Are there any periods in art history or artists that you find particularly intriguing?

Images, words, and music all serve as sources of power. Long-term, repetitive observation can preserve many seemingly insignificant elements. You will find a musical quality in my painting; it has certain melodic and rhythmic characteristics developed through accumulation. I keep many notebooks and record clues in my phone’s memos—fragments of thought that awaken my memory of things.

Many artists pique my interest, especially pivotal moments in art history, which often have a profound impact on me and change my understanding of painting—this is my ambition. Artists like Goya, Bacon, Caravaggio, Cézanne, and Picasso, as well as works and lyrics from many musicians, have greatly influenced me.

Can you tell us about what you are working on now, or would like to work on next?

I am currently addressing issues regarding new paintings, aiming to find more solid elements to remain in the work. In the future, I might revisit some traditions of portraiture, seeking to recreate images that interest me from my youth in my own way.

“Liu Jian: Daybreak” is on view at Santo Hall, Beijing, through October 21, 2024.