Books

How Should We Understand the Shocking Use of Stereotypes in the Work of Historical Black Artists? It’s About the Satirical Tradition of ‘Going There’

Read an excerpt from Duke art historian Richard Powell's recent book, "Going There."

Read an excerpt from Duke art historian Richard Powell's recent book, "Going There."

Richard J. Powell

In a 1992 review of artist Archibald J. Motley, Jr.’s first major retrospective exhibition, New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman acknowledged his struggles with understanding Motley’s approach to representing African Americans. “It’s difficult to get a handle on the art of Archibald J. Motley Jr….,” Kimmelman began, “50 of whose paintings are at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In the 1920s this black artist from Chicago devoted himself to painting black life, and he made portraits of family and friends that bestow on their subjects a remarkable, rarefied dignity.” Kimmelman continued, “How could he also be responsible for pictures like Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’ (1940) with its cartoonish stereotypes of the lazy farmhand snoozing under a tree and the bosomy mammy?”

Art critics were not alone in their confusion over works such as Motley’s Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’. During the two-year run of “Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist” (an exhibition I curated in 2014 for the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, and which subsequently traveled to museums in Fort Worth, Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York), I repeatedly responded to exhibition-goers about this painting. Visitors who were otherwise enthralled by Motley’s consummate portraiture, lively genre scenes, and sophisticated, colorful compositions were, like Kimmelman, troubled by the exaggerated black bodies and stereotypic settings in which they were placed. “You know, I just love Motley’s paintings,” is how many people would begin their comments, but as they turned to Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’, they would continue their remarks with, “But what about those big red lips on that fat ugly woman, and the nappy hair on that raggedy little black girl?”

Like centrifugal, double bull’s-eyes, the woman’s lips and little girl’s hair drew viewers deep into the bizarre pastorale of Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’, where barnyard critters and their human attendants seemingly share the same lineage. Standing barefoot on the steps of a diminutive wooden hut straight out of a Russian folktale, the woman in this painting—serpentine, pendulous, and exultant—comes across as more chimerical than realistic: a remotely human creature, flaying about in a shimmering, fungus-covered underworld. And her partners in corporeal outlandishness—a hulking idler in overalls, his recumbent doppelgänger in the far distance, and a pickaninny straight out of Uncle Tom’s Cabin—embodied the worst racial stereotypes imaginable that, in tandem with the pecking hens, aggressive geese, a lusty dog, a lazy cat, and a backside-revealing, knee-knocking mule, all conjured an African American phantasm of major proportions: an image of rural black life so outrageous and ridiculous as to single-handedly campaign, by negative example, for the mass migration of self-respecting southern blacks to the urban North, with nary a look backward.

Taken at face value, these grotesque figures—from the creative mind and skilled hands of an accomplished black artist—are either unadulterated stereotypes, the signs of racial self-hatred, or simply inexplicable. But if one considers Motley’s painting in the broader contexts of African American popular culture in the introspective years of the late 1930s, leading up to the 75th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, and Motley’s professed, career-long mission to “truthfully represent the Negro people,” there might be another, more tactical reason for his broad and outlandish characterizations. Rather than limiting his portrayals to a visual version of literary or historical naturalism—an approach that relies upon documenting the social conditions to help compose, script, and, eventually, to propagandize the picture—Motley deployed narrative-producing strategies of an insubordinate kind and, at times, a symbolic character. The anxieties that blacks felt in these years concerning racial discrimination, political disenfranchisement, and social hierarchies within their communities were such that, for a truth-seeker like Motley, painting realistically was only marginally effective in capturing a profound, subcutaneous black reality. Instead, what Motley’s paintings executed were complacency-jarring renderings of African Americans that, through their fictive settings and expressionistic configurations, opened floodgates of racial memories, phobias, and fantasies, so visceral and inescapable that, upon experiencing them, more authentic concepts of the race could emerge.

Motley’s rebellious side cannot be understood without considering it in the context of satire. Commonly linked to prose, poetry, or the dramatic arts, the art of satire uses a variety of literary and rhetorical devices to expose the perceived failings or shortcomings of individuals, institutions, or social groups. By way of the full spectrum of literary constructs and bit players, a satirist may employ invective, sarcasm, burlesque, irony, mockery, teasing, parody, exaggeration, understatement, or stereotype in a discursive presentation, all to hold his or her predetermined target up to extreme ridicule and scorn.

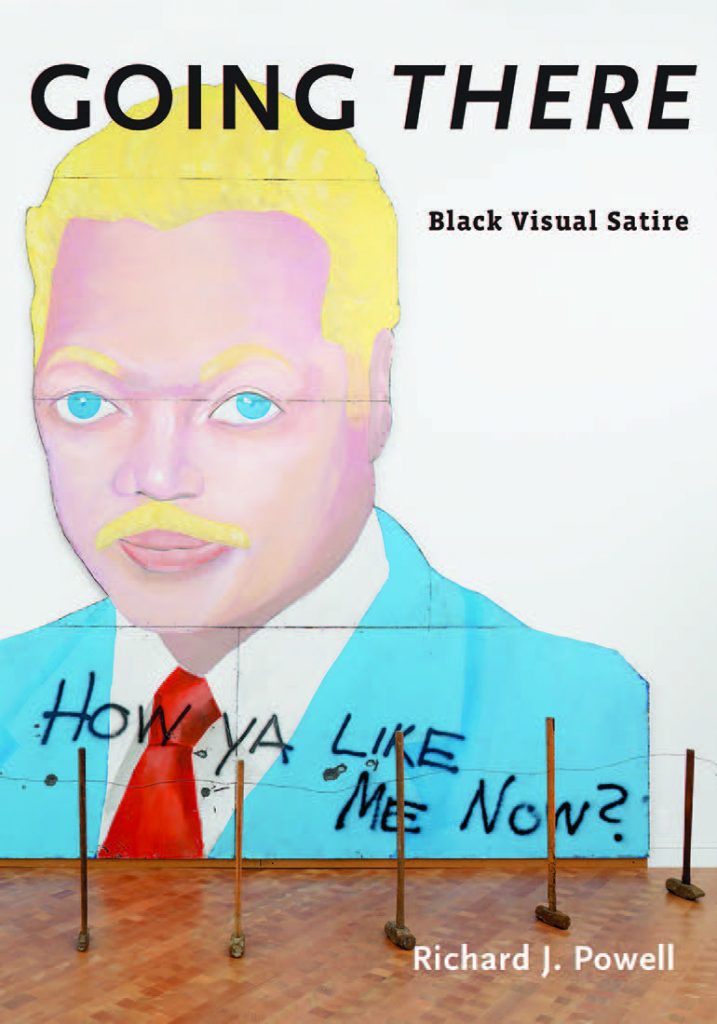

The cover of Richard J. Powell’s book Going There. Courtesy of Yale University Press.

[This book] Going There: Black Visual Satire proposes that the art of satire not only has a long-standing and infamous place in world culture, but that it also has a distinctly African American lineage and presence in modern and contemporary visual art. The challenge of developing a set of working definitions for satire is itself a formidable task, but locating this genre in a black American tradition of visual, verbal, and performative practices raises the intellectual stakes and poses multiple questions about art, its reception, and its repercussions. One of those questions is the notion of creative risk and how satire relentlessly puts the artist and the artwork’s audience in an antagonistic relationship: a situation that, rather than fostering comprehension and degrees of certainty, fuels the effrontery and confusion for which satirical works are notorious. Another issue this study investigates is the logic and the rationale behind deploying stereotypic and racist referents in black satirical art, and whether this strategy achieves the artistic objectives of its creators. Finally, the dialectical paradigms that the art of satire invariably bring to the surface—artist and audience, words and images, comedy and crisis, and mockery and valor, to name a few—complicate a straightforward understanding of this form of discourse. Apperceptions of satire’s motives and targets that also take into account the biographical and historical contexts of its initiators further confuse the critical enterprise but, as Going There: Black Visual Satire shows, these multifocal inquiries intercept and analyze satire’s active ingredients and greatly assist interpreters in measuring its overall effectiveness.

Although firmly ensconced in literature, satire and its constantly changing, combustible aspects may be expressed more powerfully in visual art. Utilizing caricature and its propensity for visual shorthand, anatomical distortion, narrative hyperbole, and symbolism, artists since antiquity have produced striking and often incisive commentaries on the peoples and events of their times. An ancient Egyptian limestone painting of a cat submissively approaching a seated, corpulent mouse demonstrated that, even in New Kingdom Egypt, an artist felt empowered enough to question conventional social hierarchies, albeit through an illustrated animal fable. The late 15th-century panel paintings by the Netherlandish artist Hieronymus Bosch, depicting apocryphal scenes of folly, gluttony, and miserliness, are paradigmatic of this artist’s mockeries and condemnations of religious heretics and hypocrites, via his visual renderings of metaphors and puns.

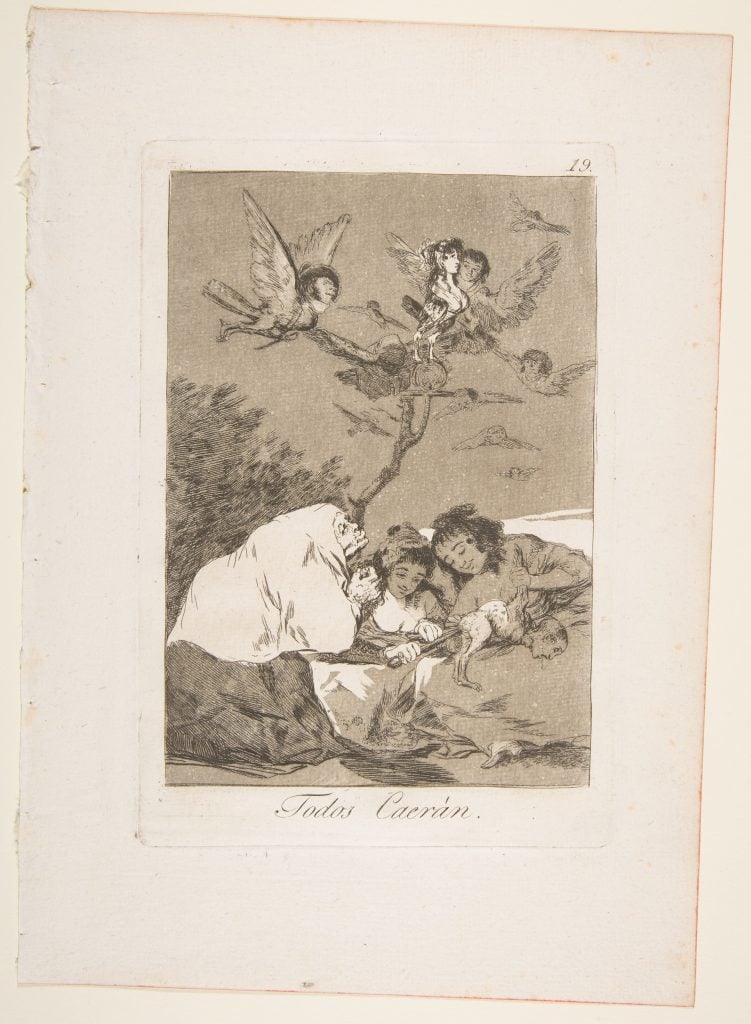

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, Plate 19 from Los Caprichos: All Will Fall (Todos

Caerán) (1799). Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

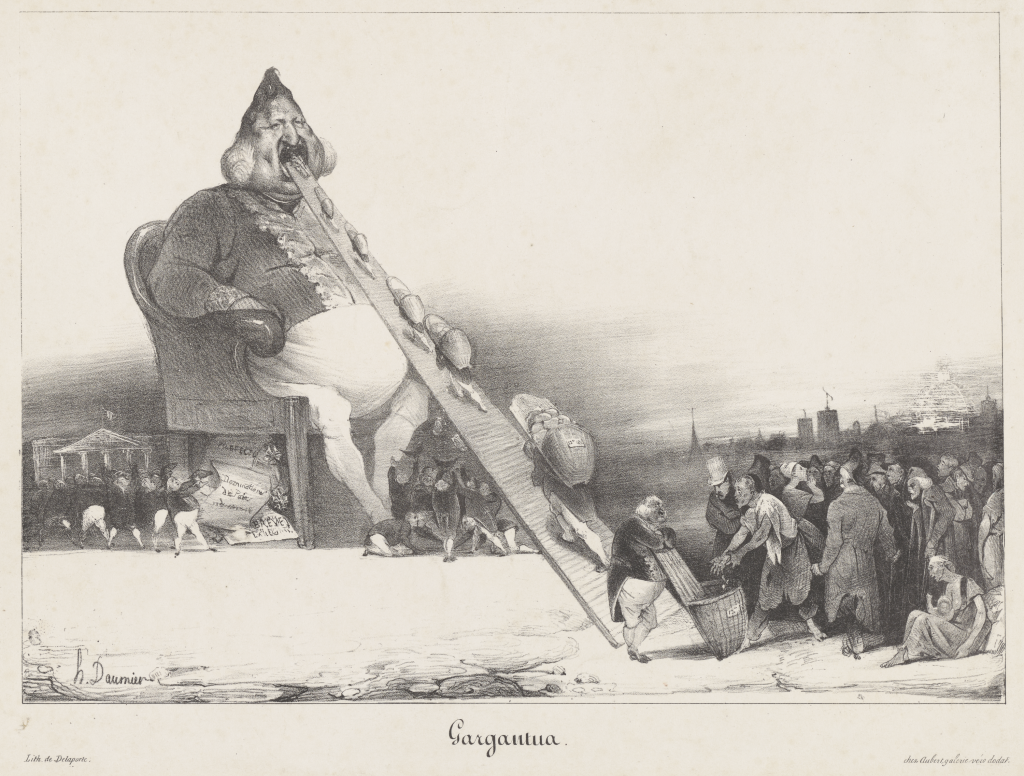

Visual satire’s illustrious triumvirate from the early modern periods of Western art—England’s William Hogarth, Spain’s Francisco Goya, and France’s Honoré Daumier—placed hard-hitting commentaries about peoples and politics at the very center of their paintings and prints, giving particular weight to the pretentiousness of elites, greed and corruption within the professional classes, and vanity across the entire social spectrum. The 20th century—with its unconventional warfare, geopolitical realignments, and interminable deliberations from decade to decade about human rights and changing social mores—provoked countless artists to unapologetically satirize the defects and failings of the status quo, from the antiwar and anti-capitalist statements of George Grosz and David Smith, to the post-Hiroshima expressions of human vulnerability and military madness by sculptors Ed Kienholz and Robert Arneson.

Historically, the preferred art media for visual satirists were the graphic arts (that is, drawing and printmaking) and, since the 20th century, film and video, in which pictorial criticisms were often accentuated by a memorable title, a wry caption, or a provocative, accompanying narration. The roots for this collusion between image and text were established in the 18th and 19th centuries, when British artists such as Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson, and James Gillray both delighted and antagonized audiences with irreverent broadsides and sardonically captioned comics that directed critical barbs and fault-finding charges at all levels of society. “One of the key changes that took place during the 17th century and which eventually multiplied to become a major social force during the 18th century,” writes historian Steven Cowan about the growth of literacy in England, “was the twofold process of the secularization of reading amongst the poor and laboring classes and the transformation of reading practices from being essentially private . . . into being freely acknowledged and performable within the public domain.” Satirical graphic art with incisive, witty captions was clearly part of this literacy-generating curriculum. Across the channel, French caricaturists Honoré Daumier and Charles Philipon wreaked comparable havoc with their drawings and cartoons of people, largely in the illustrated satirical journals La Caricature and Le Charivari. In the United States and, notably, in the years immediately following the Civil War and coinciding with the global financial crisis in the 1870s, political cartoonist Thomas Nast combined scathing caricatures of politicians and social policies with polemical declarations and combative subheadings, which irrevocably set the template and tenor in American editorial cartoons for more than a century.

In the relatively short history of Western cinema, satirizing warfare, politics, and powerful institutions such as the mass media has been very popular, whether the specific target was a particular figure, as in Nazi Germany’s Adolf Hitler in Charles Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and North Korea’s Kim Jong-il in Trey Parker’s Team America: World Police (2004), or governing institutions and political systems, as in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985). At the turn of the 21st century, when many filmmakers rediscovered and eagerly embraced satirical frames of reference in their work, director Spike Lee created Bamboozled (2000), a film that directed its outrage not just toward contemporary mass media and its lowbrow entertainment designs, but toward racial stereotypes and their insidious circulation throughout American life. Scattered throughout Bamboozled are behind-the-camera soliloquies, the protagonist’s disembodied confessionals, and “fourth wall” explanations that, when juxtaposed against the film’s script and plethora of stereotypic props, infused Lee’s story line with both keen social insights and emotionally ambivalent musings.

Honoré Daumier, Gargantua (1831). Photo: Yale University Art Gallery.

The give-and-take in visual satire between image and text is fundamental to developing a working definition of this particular idiom. In his short but useful essay “Pictorial Satire: From Emblem to Expression,” literary critic and William Hogarth specialist Ronald Paulson put this issue at the forefront of his treatise, paraphrasing from art historian Ernst Gombrich’s essay “The Cartoonist’s Armory” the idea that words have a precedence over images, and that “a form of ekphrasis—a poem reprised in an image or, alternatively, a picture put into words” commonly operates in satirical imagery. But after Paulson briskly carried his readers through pictorial satire’s classical and Christian models, the roles of narrative and rhetoric more broadly, the implementation of Rococo styles and their gestures toward the grotesque, and, finally, the elements of parody, caricature, and humor in pictorial satire, he qualified Gombrich’s textual precedent, or at least its capabilities, with the actuality of the multiple readings (or “multiple gestalts”) for pictures: a heterogeneous component whose interpretative possibilities in graphic satire “may have ultimately a greater potential for subversion . . . than [the] verbal.”

When artists are not exclusively relying on text or narrative, the imagery often has an uncanny way of taking control of an artwork’s accompanying text or title and, then, pressing that covert visual realm and/or associative dimension into illuminating recalibrations of the picture’s subject. “When Marx in Capital asks what commodities would say if they could speak,” art historian and theorist W. J. T. Mitchell reminds us in What Do Pictures Want?, “he understands that what they must say is not simply what he wants them to say. Their speech is not just arbitrary or forced upon them, but must seem to reflect their inner nature as modern fetish objects.” Similarly, one could say that images are rarely subservient to their titles or accompanying narratives but, instead, hijack these textual guideposts into performing supporting roles in a frequently inchoate realm of optical illusions, pictorial traces, and ideographic symbols that converse with the viewer’s inner angels and demons. Channeling in Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’ a virtual songbook of blues singers and their lyrics of unrequited love and desertion—such as Ma Rainey’s “Boys, I can’t stand up; I can’t sit down / The man I love has done left this town,”or Blind Blake’s “Ain’t no need of sittin’ with my head hung down / Your black man ought to get outta town”—Archibald Motley reworked the conventional social realist context of American scene painting in his canvas and broadcasted these blues-influenced sorrow songs, satirically, from a surrealistic, “down-home” backwater, and their ecstatic howl (or is this an emancipatory shout-out?) from the jaws of an otherworldly figure.

Motley’s dual targets in Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’—the southern United States’ disputably backward African American underclass and, in sharp contrast, the urban North’s “black bourgeoisie” and its paralyzing paranoia concerning caste and class—are, admittedly, unlike the satirical vehemence of, say, Weimar Germany’s most reproachful, mudslinging artist, George Grosz. And yet, as an African American satirizing his fellow African Americans, Motley undertook in Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’ a comparable challenge: a broad character sketch that, not unlike Grosz’s antiwar sentiments and parodies of modern German life, lampooned the blues tropes of abandonment and loss and, simultaneously, mocked the socioeconomic biases and color prejudices within Motley’s own black middle class.

As the virulent responses to Motley’s Lawd, Mah Man’s Leavin’ demonstrated, the social and psychological impact of visual satire is huge. For most people, being the target of criticism is, of course, embarrassing and painful, but satire’s peculiar blend of censure, wit, and ridicule brings an especially cutting quality to the criticism, enough to push the targets of satire toward the metaphorical and literal edge. Political and religious authoritarians have long recognized satire’s derisive potential (and felt its sting) and, at moments of heightened political tensions and social dissent, political cartoonists are frequently among the first victims of the censors.

Two of the most notorious cases in recent history of political cartoons instigating religious figures and governmental officials to take public, censorious actions—cartoons by Kurt Westergaard in 2005 of the prophet Muhammad, published in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten, and cartoons by Zapiro (Jonathan Shapiro) in 2009 of “The Rape of Justice” being perpetrated by South African president Jacob Zuma and his political allies, published in the South African newspaper Mail and Guardian—laid bare the inflammatory repercussions of contemporary visual satire, as well as the competing ideological positions such cultural skirmishes bring to the surface. These two instances of political cartoons generating social unrest and national introspection, as detailed and analyzed by literary critic Mikkel Simonsen, raised a very complicated situation within Denmark and South Africa: balancing a democracy’s commitment to freedom of expression with constituents (including the religious leaders and government officials in the political cartoonist’s line of fire who, whether justified or instinctively, question the satire’s political motives, critical reach, or moral integrity. Paradoxically, it is frequently within democracies, points out Simonsen, “where governments and media use exceedingly powerful measures to systematically indoctrinate as well as infringe on our human rights.” Simonsen continues, “It is increasingly difficult to tell right from wrong as the democracies, within themselves, and in turn with the world around them, change.” That something as seemingly innocuous as a flippant drawing has the capacity to stir people’s emotions and, in the most extreme cases, incite them to violence argues for taking these works of art seriously and, considering the satirical context in which they operate, querying their social value and underlying power.

From Going There: Black Visual Satire by Richard J. Powell. Published by Yale University Press in association with the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, in November 2020. Reproduced by permission.