Art History

The Girl With a Pearl Earring’s Lavish Jewel May Be a Fake and 4 Other Secrets Scholars Have Uncovered in the Work of Vermeer

What's happening under the surface of the Dutch painter's canvases offers insights into his enigmatic oeuvre.

What's happening under the surface of the Dutch painter's canvases offers insights into his enigmatic oeuvre.

Katie White

The Sphinx of Delft is a fitting moniker for Johannes Vermeer, the 17th-century Dutch artist about whom, despite his wild fame, so little is actually known. His oeuvre was small—only 35 or 36 extant works are known or agreed upon— but over the course of the centuries intervening since his death in 1675, it has sparked seemingly boundless fascination, speculation, and analysis.

The French art historian Théophile Thoré-Bürger bestowed the “Sphinx” nickname onto Vermeer in the 19th century. Thoré-Bürger had plucked Vermeer from semi-obscurity—though moderately successful in his lifetime, the artist fell out of fashion soon after his death—and used the nickname to describe the enigmatic, strangely modern, and even literary feel of the work.

Vermeer’s paintings depict deceptively simple scenes—a woman reading a letter at a window, a maid pouring milk, a music lesson—but Thoré-Bürger’s intuition that they were keeping back untold secrets was absolutely correct. Over the centuries, conservators, scientists, curators, and art historians have discovered a number of surprising mysteries, tricks, and changes in Vermeer’s paintings.

Below we’ve pinpointed a few favorites that have allowed us to see Vermeer’s work in a whole new way.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Reading a Letter at the Open Window (1657-59). © Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photo: Wolfgang Kreische.

The centerpiece of the Vermeer exhibition currently on view at Dresden’s Gemäldegalerie is the newly restored Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (1657–59)—a painting which has held its own flirtatious secret for centuries.

The work, which shows a young woman reading a letter by the light of a window, is one of several the artist made around the subject. The recent restoration has uncovered a painting of Cupid, the god of desire, hanging on the wall behind her.

While scholars have known of the existence of the painted-over god for some 40 years, they had until recently believed Vermeer had obscured the image himself. But studies have now revealed that the paint was added after Vermeer’s death, perhaps even several decades later.

The image of Cupid, who tramples on a mask (a symbol of deception), is one Vermeer probably owned—it makes appearances in three other canvases by the artist. What’s more, it might hint at the romantic, even illicit, nature of the letter: the sending and receiving of letters was regarded as quite risqué in Vermeer’s day and age (think: getting caught in the act of sliding into someone’s DMs).

Johannes Vermeer, Officer and Laughing Girl. Collection of the Frick Museum.

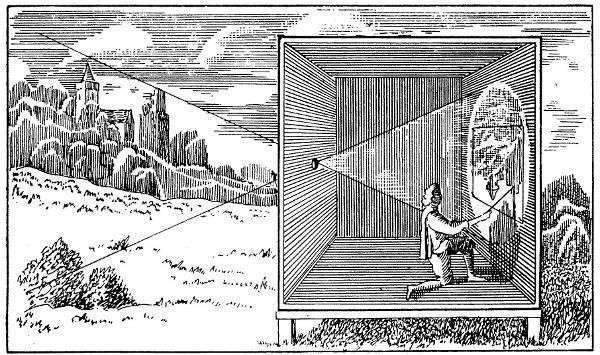

When it comes to Vermeer, what’s missing can often be as revealing as what’s on the canvas itself. While X-rays have illuminated a host of contextual changes in Vermeer’s compositions, the absence of underdrawings or sketches to delineate the very beginnings of his works has led many to wonder if the artist worked with the aid of a camera obscura—a device or room with pinhole used to project inverted images of a subject onto a darkened surface. Instead of revealing sketches or outlines, X-rays of Vermeer’s canvases show that the artist skipped ahead to the process of underpainting, directly applying paint with a conclusiveness that might imply he was tracing the images.

The American artist Joseph Pennell first suggested the possibility in 1891, when he noted that the male figure in Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl was almost twice the size of the girl across from him—a decidedly photographic proportion, rather than painterly perspective. Several years ago, in her book, Traces of Vermeer, the author Jane Jelley put the hypothesis to the test, orchestrating experiments that attempted to uncover how exactly Vermeer might have gone about using the camera obscura. Her results—made with era-specific materials—were strikingly similar.

Engraving of a “portable” camera obscura in Athanasius Kircher’s Ars Magna Lucis Et Umbrae (1645).

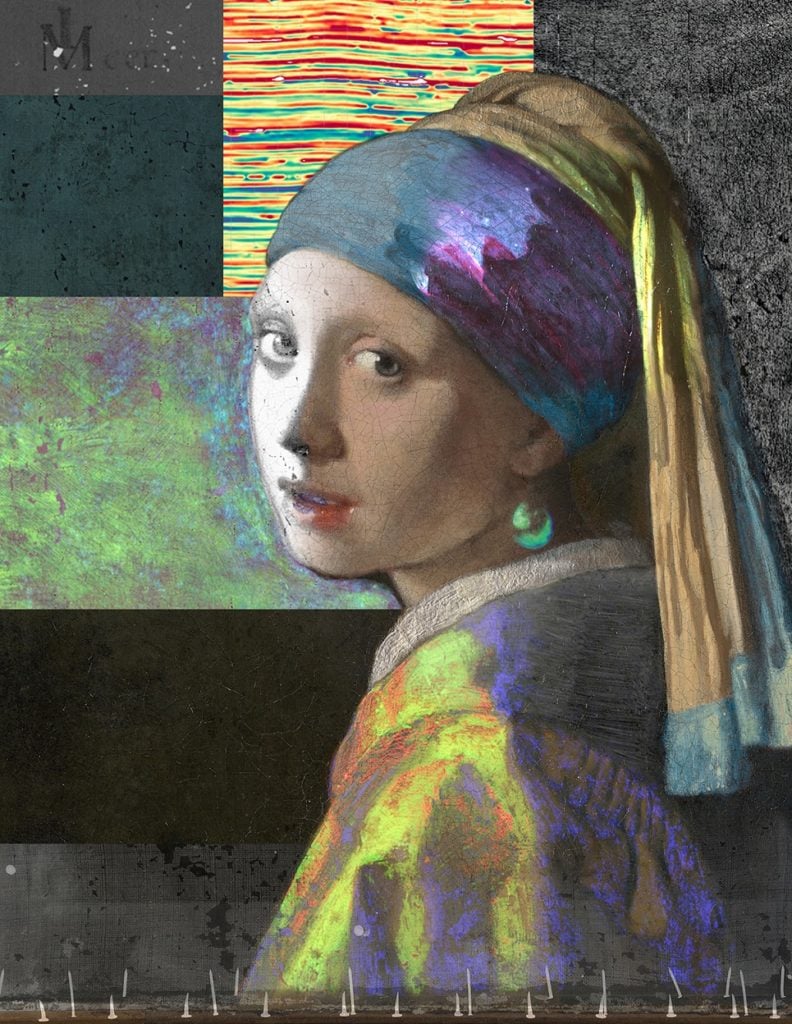

More recent X-rays of Girl with a Pearl Earring seem to lend further credence to the theory. The work’s underpainting, which was made with leaded paint distinct from the rest of the composition, revealed that the highlights on both the pearl and the girl’s right eye were perfectly spherical—aka the shape of a pinhole—in Vermeer’s first pass, details which he altered as the painting progressed.

Composite image of Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring from images made during the “Girl in the Spotlight” project. Image courtesy of Sylvain Fleur and the “Girl in the Spotlight” team.

A Dutch Golden Age masterpiece, the Girl With a Pearl Earring has spurred countless interpretations (and, yes, even a movie) with many pondering over the identity of the serene young woman in the painting. Some have argued that the woman was intended as an ideal or archetype of beauty rather than a specific person. These historians have pointed to the vacuous black background, as well as the girl’s lack of eyebrows or eyelashes as indications that the painting is not meant to be “of this world” but rather an almost sculptural ideal.

Whatever Vermeer’s intention, in April of 2020, the Mauritshuis museum in the Hague used new technological tools to reveal that Vermeer had indeed painted delicate eyelashes, which subsequently faded from view. Oh, and that blank dark space behind her? It was originally meant to depict a green curtain.

More alarmingly, perhaps, the museum’s studies suggest that the girl’s lavish pearl earring might actually be a fake. In a blog detailing the studies, Mauritshuis’s paintings conservator Abbie Vandivere wrote that it might not even be a pearl at all. “Costume and jewelry specialists believe that it’s too big to be real,” she wrote. “Perhaps Vermeer exaggerated it a little to make it more of a focal point of the painting… At high magnification, you can see that Vermeer painted the pearl with only a few brushstrokes of lead white.”

Johannes Vermeer, The Art of Painting (1666-67). Collection of Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Wall maps were a popular decorative fixture of Dutch interiors during the 17th century, and a particular point of pride in the influential mercantile nation. Maps were often included in paintings simply to add some compositional drama to otherwise bare walls. Vermeer’s maps, however, were often rendered with a cartographer’s sensitivity and detail.

Thoré-Bürger dubbed the obsession with detail Vermeer’s “mania for maps.” Some of Vermeer’s maps have even been identified. In both Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (1663) and Officer and Laughing Girl (1657), Vermeer includes a map designed by Balthasar Florisz van Berkenrode in 1620 and printed by Balthasar Jansz Blaeu. The map was likely in Vermeer’s possession and might have been a nod to another aspect of the artist’s life: to support his family, Vermeer ran a shop from his home—where he sold, among other things, sought-after maps.

Johannes Vermeer, A Girl Asleep (1657). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Maids were the subjects of much salacious gossip in 17th century Europe; in Holland paintings depicting the promiscuous comings and goings of these women became popular moralizing tales or bawdy genre scenes. In one of his earliest genre scenes A Maid Asleep (ca. 1656-57) a young woman of a household staff is shown dozing at a table alongside a glass of wine. A mussed up table dressing hints at some kind of revelry, as does a second toppled (and now obscured) wine glass.

In its final version, however, the painting is not particularly instructive, and rather a reflection of Vermeer’s fascination with light and perspective. X-rays, however, show that Vermeer had originally included the figure of a man in the doorway, a detail he later chose to omit, perhaps as too obvious a gesture. As is so often the case with Vermeer’s paintings, what he hides can be the most revealing.