People

Seattle University Removes Chuck Close Work in Response to Sexual Harassment Allegations

Some observers wonder whether museums should include asterisks next to the names of accused artists.

Some observers wonder whether museums should include asterisks next to the names of accused artists.

Sarah Cascone

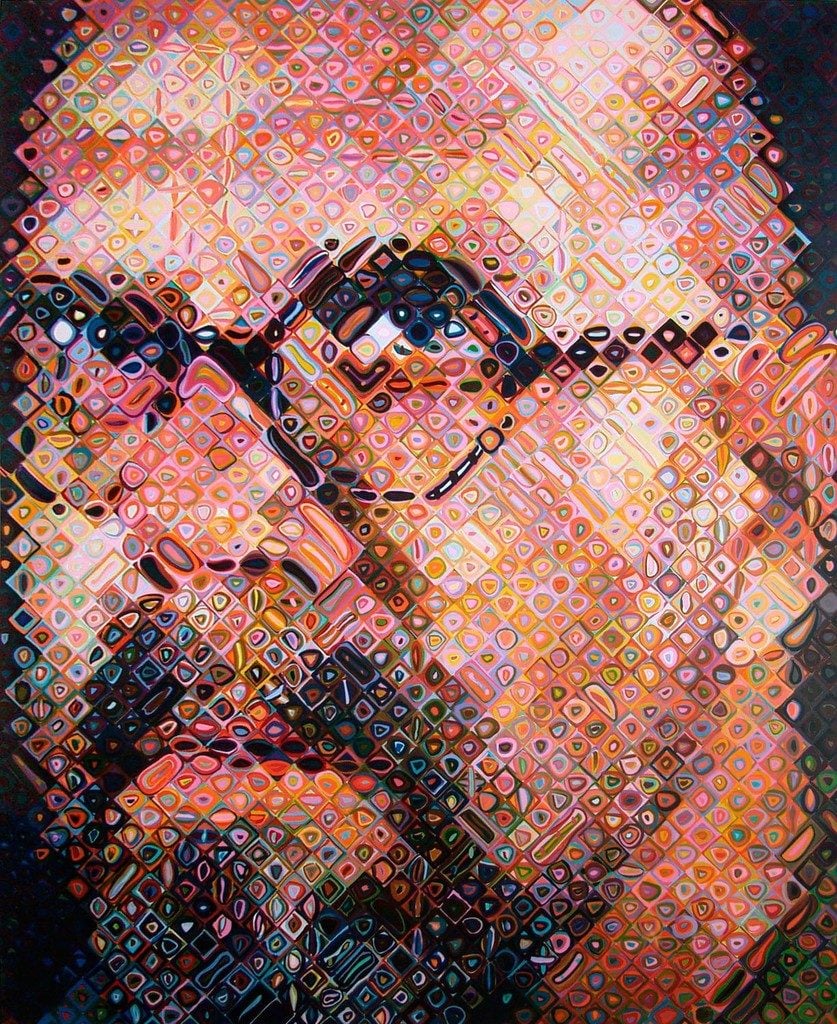

The fallout from sexual harassment allegations against Chuck Close continues as Seattle University removes a prominently displayed self-portrait by the artist. The work, Self-Portrait 2000, a serigraph made with 111 different screens and overprints and valued at $35,000, was formerly on display in the second floor lobby of the school’s Lemieux Library. Now, an oil painting by Linda Stojak hangs in its place. (Both works were donated to the university.)

“We were concerned about potential student, faculty or staff reaction to seeing the self-portrait, and decided that the prudent and proactive course of action would be to replace the self-portrait with another work,” wrote representatives of Seattle University in an email published in the Stranger. They noted that the decision was made “given escalating developments regarding sexual harassment and sexual misconduct scandals.”

Several women have accused Close of behaving inappropriately and making lewd remarks about their bodies when they posed as models for him. Close’s lawyer did not immediately respond to a request for comment from artnet News.

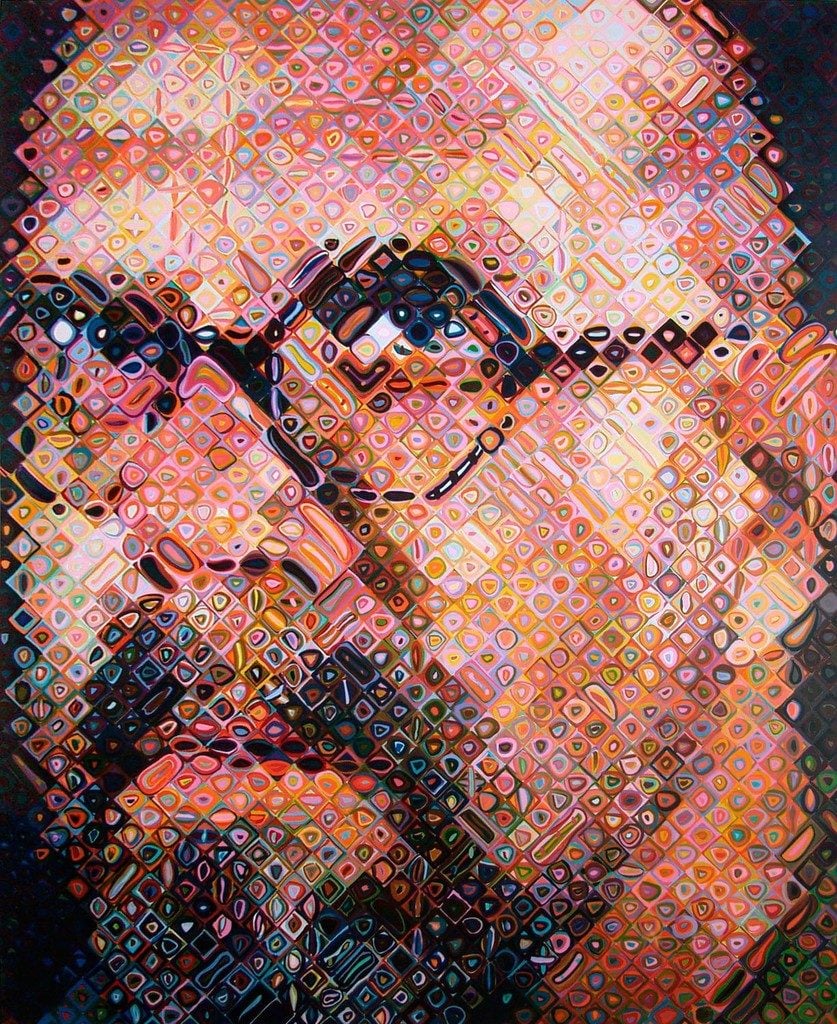

Linda Stojak, Untitled (Shirley). Courtesy of the artist.

In response to the allegations, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, postponed an upcoming exhibition of Close’s work. Originally scheduled to open May 13, the show, “In the Tower: Chuck Close,” has been postponed indefinitely, as has a planned exhibition for photographer Thomas Roma, who stands accused of pursuing sexual relationships with several of his students at Columbia University.

The claims against Close and Roma are part of a much larger wave of accusations against high profile men in a number of fields, triggered by the eruption of the Harvey Weinstein scandal.

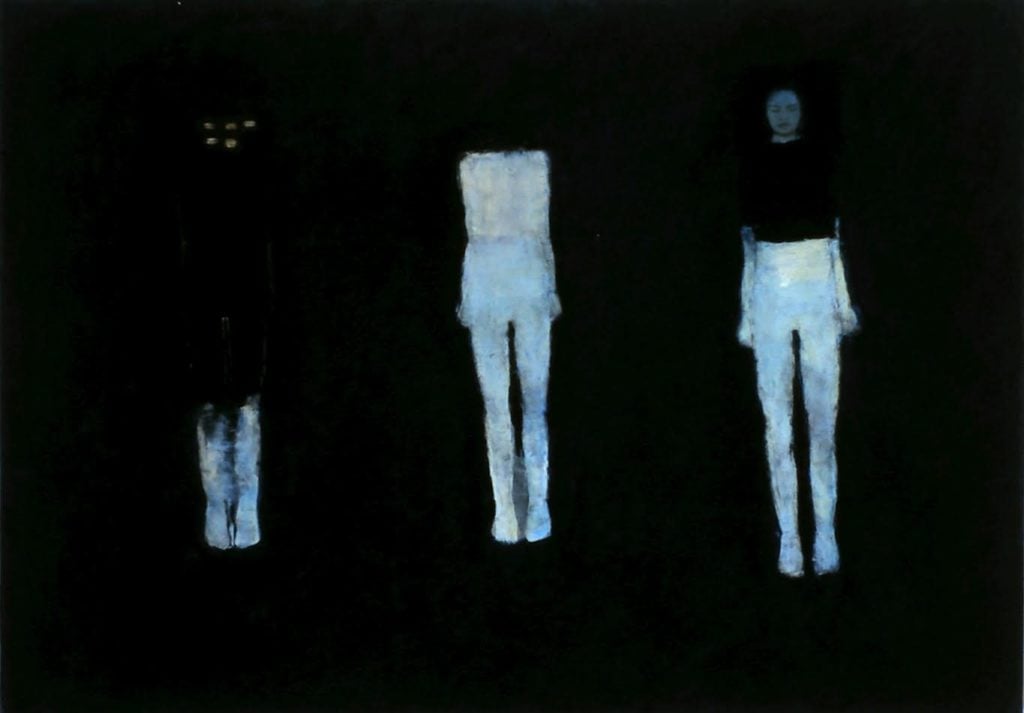

Chuck Close, William Jefferson Clinton (2006). Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, lent by Ian and Annette Cumming, ©Chuck Close.

With closer scrutiny of artists’ behavior, institutions will continue to reconsider whether or not to display work by those accused of sexual misconduct. This weekend, the New York Times wondered whether museums ought to include asterisks next to names in such cases, the way that they sometimes include damning biographical details about controversial portrait sitters.

“How much are we going to do a litmus test on every artist in terms of how they behave?” asked Jock Reynolds, the director of the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, in the Times. “Pablo Picasso was one of the worst offenders of the 20th century in terms of his history with women. Are we going to take his work out of the galleries? At some point you have to ask yourself, is the art going to stand alone as something that needs to be seen?”