Art World

Alexander Calder’s Complete Archive Is Now Entirely Online—Discover Some of the Rare Photos, Sketches, and Ephemera Here

Click through the newly unveiled research archive before seeing MoMA’s ambitious new Calder show.

Click through the newly unveiled research archive before seeing MoMA’s ambitious new Calder show.

Taylor Dafoe

An ambitious exhibition that tries to get its arms around the breadth of Alexander Calder’s output is opening at the Museum of Modern Art this weekend. That’s no easy task, it turns out.

Just look at the Calder Foundation’s newly unveiled online research archive, the digital home of hundreds of photographs, documents, works of art, and other materials related to the American sculptor—much of it previously unpublished or otherwise rarely seen—and all of it free to access.

It will do for hardcore Calder-heads what IMDB does for movie buffs. The kitchen sink archive is chronologically organized and searchable by genre of artwork (“hanging mobile,” “oil painting,” etc.); material type (films, photos, exhibition documents); and the artist’s career stages (“1937-1945: Public Commissions and the War,” for instance.)

But historians aren’t the only audience here. The site, designed by Brooklyn-based studio CHIPS, also offers up a more palatable tasting menu of the artist’s greatest hits in the form of illustrated timelines, interactive maps, and microsites dedicated to specific topics.

The idea, says Beryl Gilothwest, who led the three year project for the foundation, was to both “approximate the experience of actually being in a physical archive,” and introduce new opportunities to “facilitate a dynamism” that’s missing while shuffling through boxes and papers. For instance, photos featuring a Calder artwork, even if it’s just in the background, link to a page detailing the specific piece. That page will then direct you to the exhibitions in which that work was included, which will direct you to the artist’s career timeline. Every piece of information connects to another; there are no dead ends.

“You can see these sorts of connections that, ultimately, can’t even really be experienced when you’re physically in the archive,” says Gilothwest. “It became more than we ever anticipated.”

Indeed, it can be a fun exercise to click through the materials, choose-your-own-adventure style. What quickly stands out is the sheer scope of Calder’s career—the places it brought him and the many artists and institutions with which he converged along the way.

With that in mind, we asked Gilothwest to pick out some of his favorite rare materials that he discovered while digitizing the archive, and explain them in his own words. See his selections below—then catch some of them in person this weekend at MoMA’s show, “Modern from the Start.”

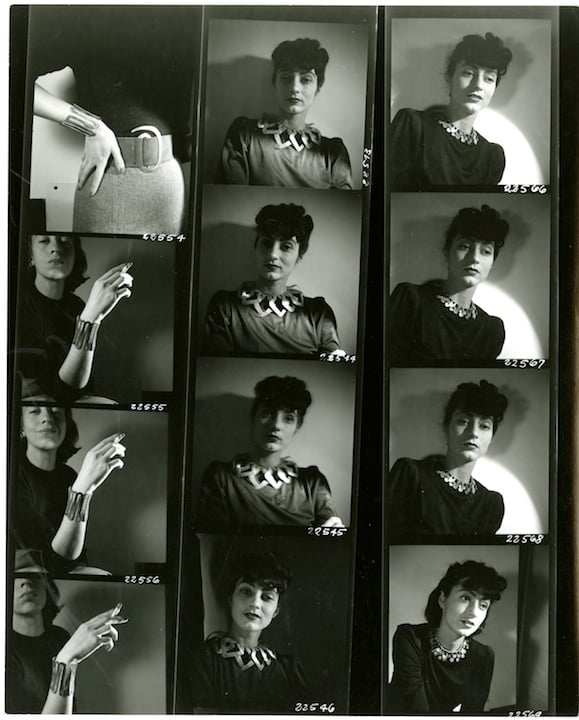

Contact sheet showing Lee Krasner and Mercedes Matter modeling Calder jewelry, 1940. Photograph: Herbert Matter. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“The Swiss photographer Herbert Matter amassed arguably the most important visual record of Calder’s life and career, particularly from the 1930s to the ’50s. In 1940, he enlisted his wife, Mercedes Matter, who was an Abstract Expressionist painter, and her friend, the legendary painter Lee Krasner, to model Calder’s jewelry for him. I love the moodiness of these photographs, evoking a quality of German Expressionist cinema. It also presents the unlikely intersection of Calder and Krasner. In our online archive, there’s also a photograph of Calder and Jackson Pollock (Krasner’s husband) on the beach in East Hampton in the late 1940s.”

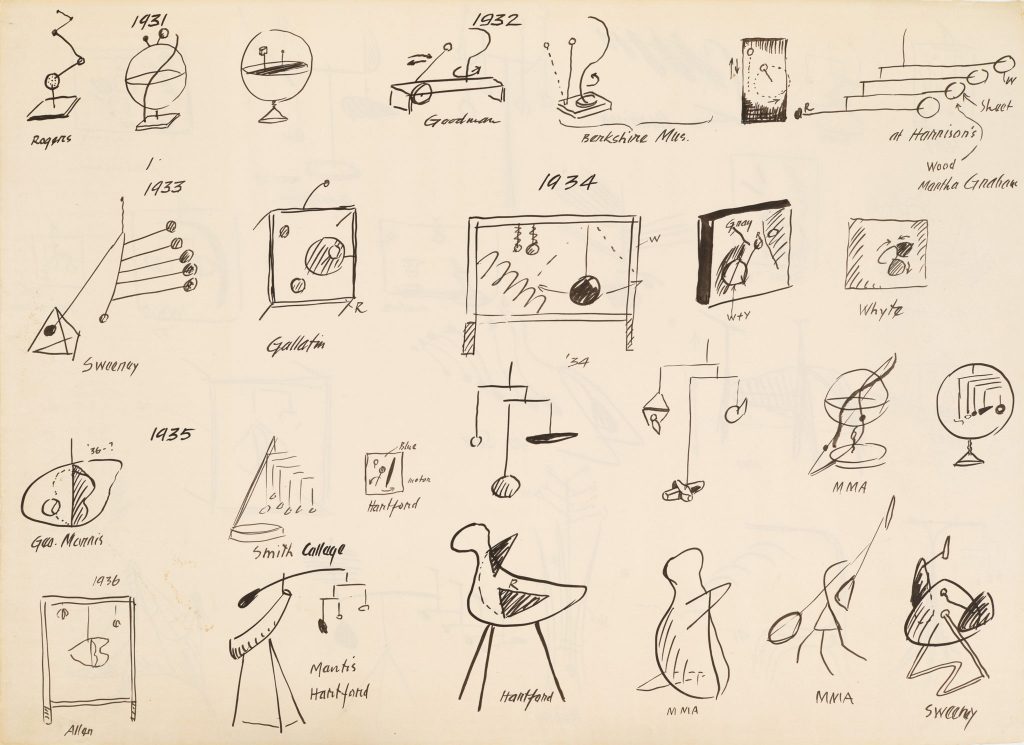

Untitled (double-sided drawing, 1943). Made in advance of “Alexander Calder: Sculptures and Constructions” at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“This fascinating document has never been exhibited or published, at least until ‘Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start.’ Calder Foundation president Alexander S.C. Rower has written an essay about it for the catalogue. Calder made it in 1943, likely in the wake of a conversation with curator James Johnson Sweeney about his forthcoming retrospective at MoMA. Of the 48 works depicted, 32 of them ended up in the show. The drawing, which Calder made from memory, is rare because of its scale (Calder often made inventory drawings, but they were much smaller). It is especially interesting though because Calder drew his works in roughly chronological order. By doing so, he gives us an essential insight into how he viewed his trajectory as an artist.”

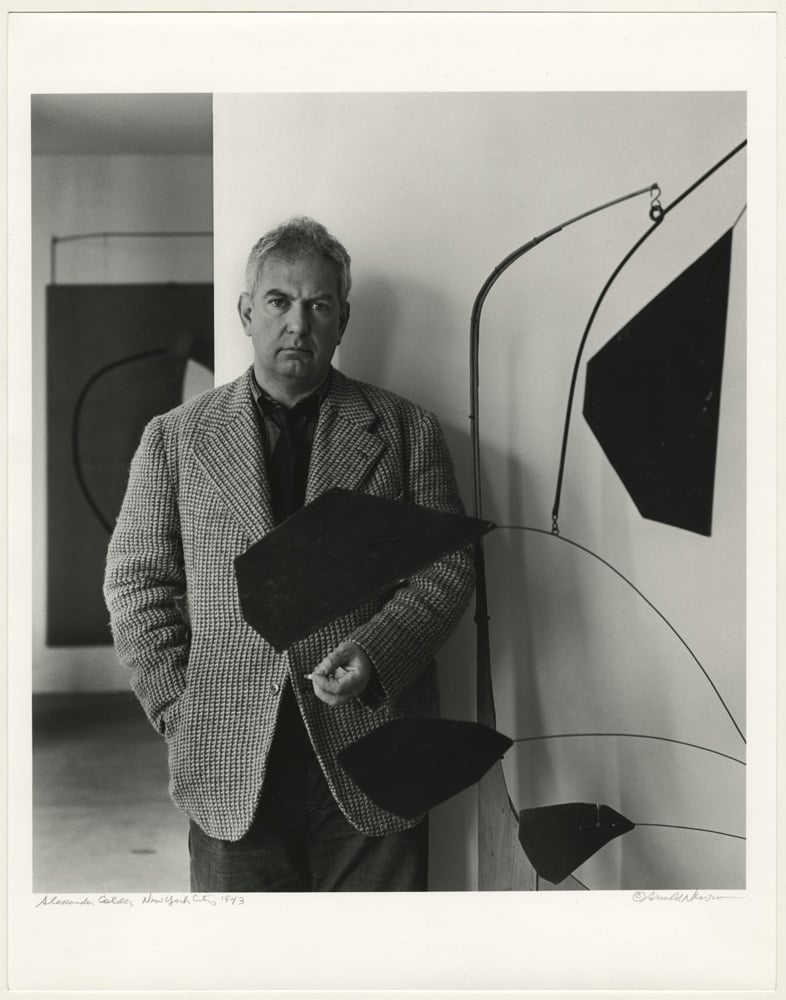

Calder at “Alexander Calder: Sculptures and Constructions,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 20 September 1943. Photograph: Arnold Newman © Arnold Newman. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Many of the most important photographers of the 20th century photographed Calder, including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Irving Penn, André Kertész, Carl Van Vechten, Gordon Parks, Man Ray, and more. Arnold Newman took this portrait of Calder in the galleries of his transformative MoMA retrospective in 1943, on the eve of its opening. The show’s extraordinary success turned Calder into one of the best-known American artists of the time, so this photograph captures a pivotal moment in his career. Newman also photographed Calder several years later in his Roxbury, Connecticut, studio.”

Martha Graham performing Judith at Columbia Auditorium with Louisville Orchestra, Kentucky, 4–5 January 1950. Photograph: Lin Caulfield. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“In this photograph, Martha Graham is performing Judith in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1950, adorned in a number of Calder’s jewelry pieces. One of the bracelets she is wearing now belongs to MoMA and is included its new show. Calder was fascinated with the idea of working on theatrical productions throughout his career, and two of the most important early projects he worked on were Graham’s Panorama (1935) and Horizons (1936). Unfortunately, no documentation of either remains, so this photograph of Calder and Graham together in a performance context is particularly precious. In our online archive there are also some great snapshots of Calder and Graham together at the opening of his MoMA show in 1943.”

Calder placing a necklace on Jeanne Moreau during the production of Nucléa, Théâtre National Populaire, Paris, 1952. Photo: Agnès Varda. © Agnès Varda Archive. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“This might be my favorite image in the online archive, largely because of the meeting of the minds depicted within. In 1952, Calder designed the sets and costumes for a production of Henri Pichette’s Nucléa at the Théâtre du Palais de Chaillot in Paris, directed by Jean Vilar. The photograph was taken by a young Agnès Varda, who was the theater’s staff photographer at the time. She initially planned to pursue a career as a photographer, but changed course in the wake of her first film, La Pointe Courte, which was released three years after this picture was taken. Varda and Calder struck up a friendship and she would photograph him on several occasions in the 1950s, including a famous series of him and his sculptures in the streets of Paris. The final piece of the story is that Calder is placing a necklace on the star of the play, the New Wave legend Jeanne Moreau. She was well known in theater circles at the time, but her breakout as a film star was still several years off.”

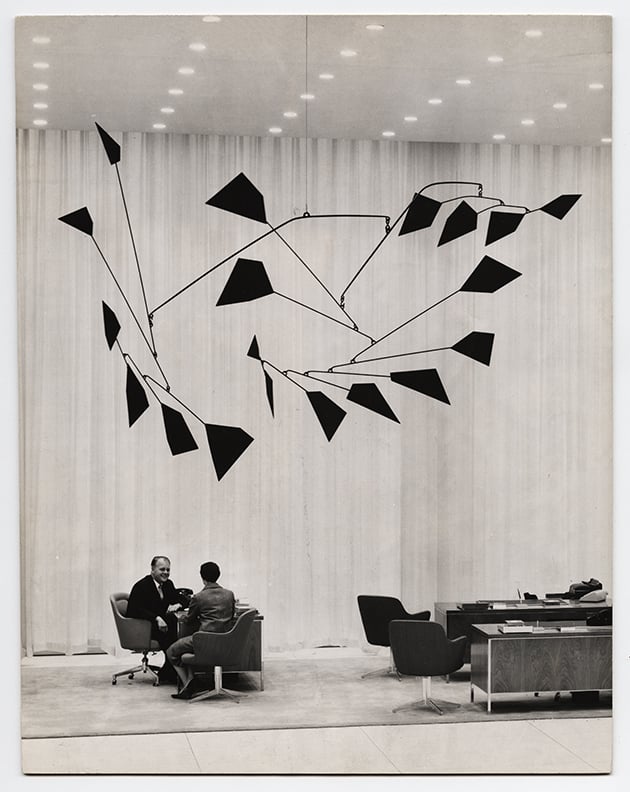

Untitled (1959), Chase Manhattan Bank, New York, c. 1959. Photo: Lee Boltin. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Calder worked with almost every important architect of his day and was friends with many of them, too, including Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, Josep Lluís Sert, and Carlos Raul Villanueva. For one of several collaborations with Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, Calder made this mobile for a branch of Chase Manhattan Bank at 410 Park Avenue in New York. It is open for business to this day. While the bank still owns the amazing mobile Calder made, it no longer hangs in the space for which it was intended.”

Calder and a nun with Black Widow (1959) outside the Chiesa di San Domenico, Spoleto, 1962. Photograph: Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“The most important documentarian of Calder’s life and career in the 1960s and 1970s was the Italian photographer Ugo Mulas. He took this photograph in Spoleto, Italy, in 1963. Calder had been commissioned by curator Giovanni Carandente to make the colossal 58-foot-tall stabile Teodelapio to stand outside the city’s train station as part of the fifth Festival of Two Worlds, an important arts festival that continues to this day. Carandente also placed modern sculptures all over the old city, including Black Widow in front of the Chiesa di San Domenico, as seen here. This is one in a wonderfully evocative series of photographs Mulas took of nuns walking by the sculpture. Black Widow was ultimately acquired by MoMA and has become a mainstay of their sculpture garden. It was just recently brought inside to be part of “Modern from the Start.”

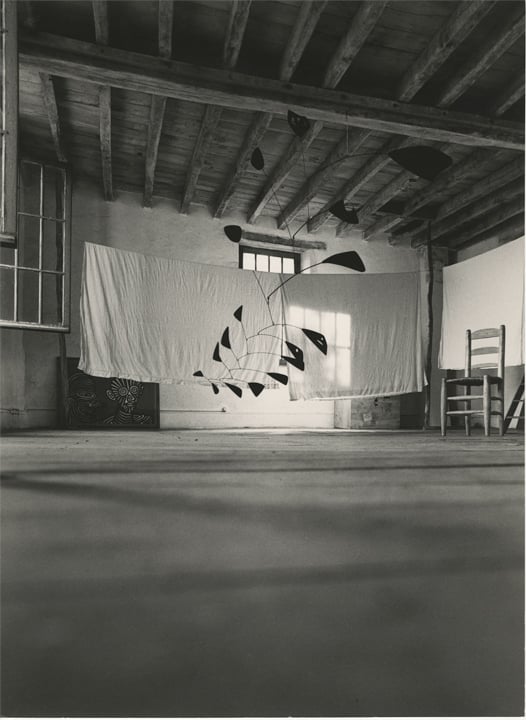

Black Mobile with Hole (1954), Moulin Vert, Saché, c. 1963. Photograph: Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“This is another photograph by Mulas from the same year, but this time in Saché, a small French village in the Indre-et-Loire. One of Calder’s finest mobiles, Black Mobile with Hole, hangs in Moulin Vert, the home of Calder’s son-in-law Jean Davidson. His very unusual house had previously been a mill and actually straddles the Indre River. Its idiosyncratic charm played a role in inspiring Calder to settle in Saché after his first visit in 1953. While Calder preferred his art to be installed in conversation with modern architecture, his taste in living spaces was far more bohemian.”

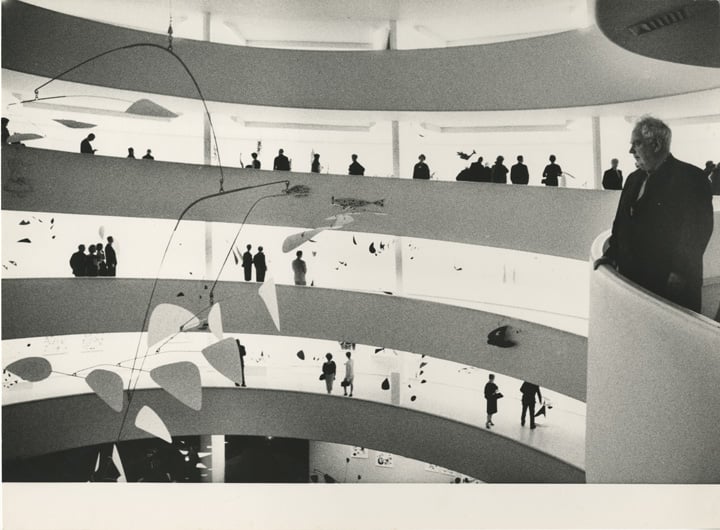

Calder at the opening preview for “Alexander Calder: A Retrospective Exhibition,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1964. Photograph: Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Here, Calder attends the opening preview of his massive retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1964. He made The Ghost, the monumental mobile in front of him, specifically for the show to hang from the dome of Frank Lloyd Wright’s building. Notably, this was the first time that the museum allowed a sculpture to be suspended from that ceiling. The work now belongs to the Philadelphia Museum of Art and hangs in its Great Stair Hall.”

The Spiral (No! to Frank Lloyd Wright) (1966) at the opening for Guggenheim International Exhibition: “Sculpture from Twenty Nations,” Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1967. Photograph: Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Around 1946, Calder was asked to create a ‘central object’ for what would eventually become Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous building for the Guggenheim. When asked to make it gold, Calder replied ‘OK, and we’ll paint it black.’ The commission never came to fruition, but Calder later made The Spiral, a motorized standing mobile with a spiraling top element of industrial brass, which was exhibited at the Guggenheim in 1967. The work’s alternate title was ‘No! to Frank Lloyd Wright.’”

New Mobilization Button, 1969. Made for the peaceful demonstration “National Mobilization to End the War” in Washington, D.C., on 15 November 1969. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“The Calders’ liberal politics turned them into staunch opponents of the Vietnam War in the 1960s. Calder made this button for a peaceful demonstration in Washington, D.C., in 1969, held by the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam. A few years earlier, the Calders took out a full-page advertisement in the New York Times on behalf of SANE, the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy.”

Les Masques (1971). Woven by Pinton Frères, Aubusson, France. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Calder made quite a few tapestries with expert weavers in Aubusson, France, in the 1960s and 1970s, including this one with Pinton Frères in 1971. In order to make these works, Calder created ink and gouache paintings as cartoons. We have added a series of these paintings to the online archive, none of which have been published or exhibited before. Calder’s wife, Louisa, also hooked several rugs with designs drawn from his paintings, several of which are also featured in the archive.”

Calder with Hervé Poulain holding BMW 3.0 CSL 24 Heures du Mans 1975 (maquette, 1975), Le Carroi house, Saché, 1975. © 2021 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Inspired by the jetliner that Calder painted for Braniff International Airlines, the French race-car driver Hervé Poulain commissioned the artist to paint a BMW 3.0 CSL in 1975. It became the first BMW Art Car, a popular program that continues to this day. Rauschenberg and Warhol are among the other artists who have participated. In this photograph, Calder and Poulain are sitting in the artist’s home in Saché with a maquette for the car.”

“Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start” opens March 14 at the Museum of Modern Art and will be on view through August 7, 2021.