Archaeology & History

Iron Age Swords Seized in the U.K. Deemed ‘Frankenstein’ Forgeries

Analysis of the artifacts showed they were modified by forgers to increase their value.

In the late 1920s, a large cache of bronze and iron weapons was discovered in the western Iranian province of Luristan, near the border with Iraq. They dated from the Iron Age and demonstrated how the region had pioneered a range of metallurgical innovations that gradually spread across the ancient Near East. For many European museums, these 3,000-year-old specimens became must-haves, which in turn drove up prices and encouraged looting.

New research from the British Museum and Cranfield University, located in England’s Midlands, suggests this increased demand for Iranian Iron Age weapons has also triggered the production of forgeries and pastiches on a scale not yet known.

The revelation arrived following the confiscation of a collection of smuggled Iranian swords at London’s Heathrow Airport by the U.K.’s Border Force. The agency sent the swords to the British Museum, which has conducted research on eight of them using a non-invasive imaging technique known as neutron tomography. It’s the first time the technique has been used on Iranian Iron Age swords with the findings published in the November 2024 edition of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

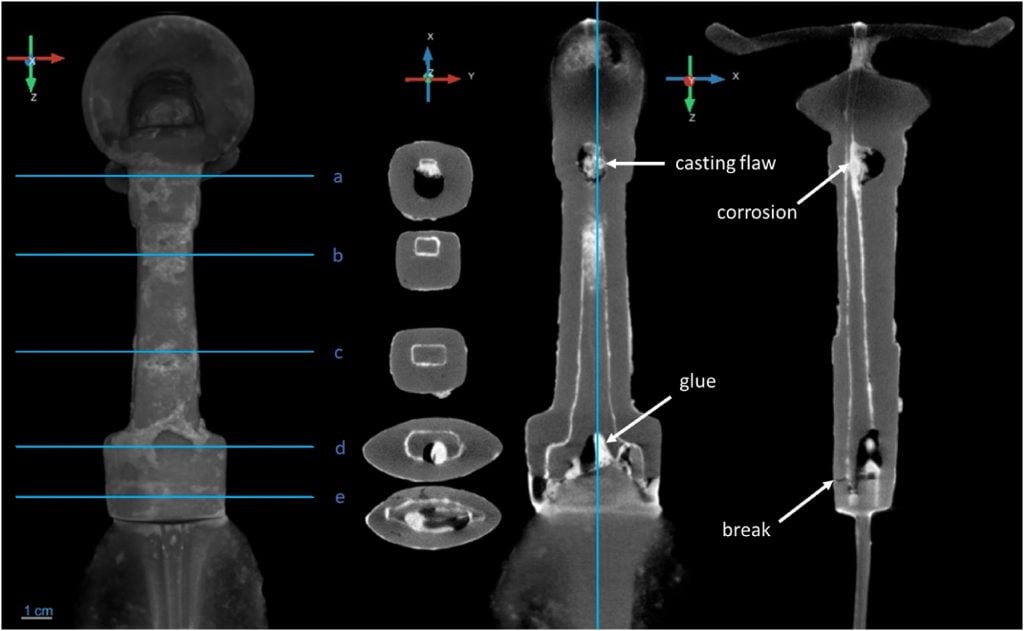

Neutron tomography shows the original blade as well as the glue or resin used. Photo: courtesy Journal of Archaeological Science.

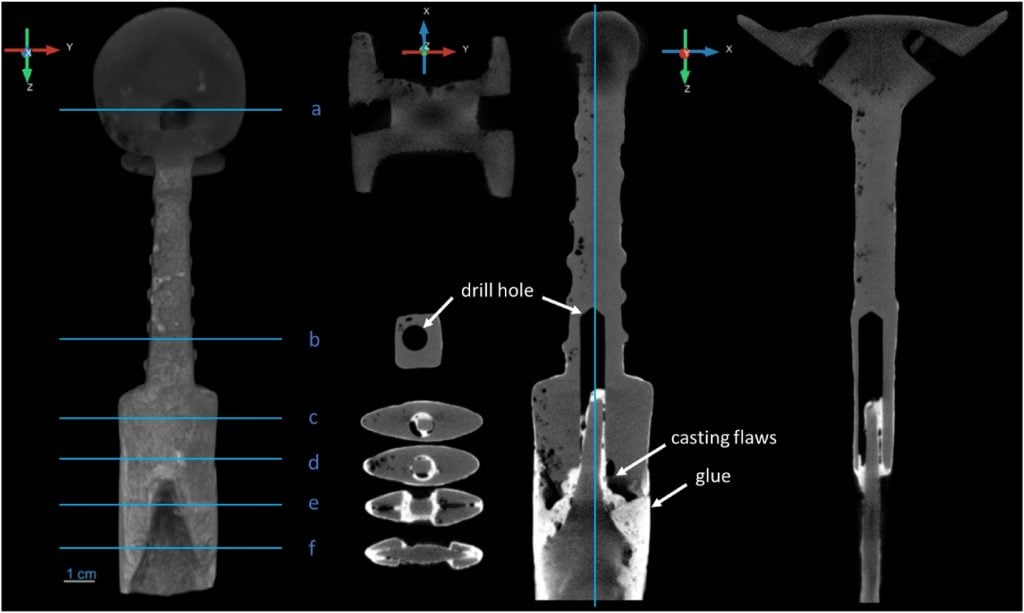

Neutron tomography, which is not yet commonplace in archaeological science, visualizes the internal structure of a subject by using neutrons and is particularly effective at identifying organic matter. Researchers were suspicious on account of discolored markings that looked like glue. Inside the swords, researchers indeed found the use of glue, as well as modern drill holes, and the fragment of a modern drill bit. The forgers’ goal was to produce valuable bi-metallic objects that archaeologists use to research the transition from bronze to iron. In some cases, bronze blades have been affixed to original iron hilts, an assemblage researchers called a kind of “Frankenstein’s monster.”

“The results reveal extensive modern modification, namely the replacement of original blades—often made of iron—with different (but probably also ancient) bronze blades,” researchers wrote in the report, “conclusively showing that ‘iron cores’ were not a technological feature in these bronze swords, but a result of modern tampering.”

Neutron tomography shows the use of glue and a large drill hole. Photo: courtesy Journal of Archaeological Science.

The findings not only evidence the prevalence of modern tampering in Iranian Iron Age swords; they also suggest that unless obtained during legitimate excavations, the authenticity of artifacts belonging to museums cannot be guaranteed. The researchers assessed that no matter if bought, donated, or confiscated from looters, it seemed highly likely that there would be further swords evidencing modification.

For researchers, evidence of fake bi-metallic swords makes it more difficult to track the spread of iron and new metallurgic techniques through the early 1st millennia B.C.E. Uncovering the prevalence of such bi-metallic forgeries will be crucial to understanding how common combining bronze and iron was in early Iron Age metallurgy.

The swords, which are part of a larger cache of seized objects, will be displayed at the British Museum before being repatriated to Iran.