Art History

Senga Nengudi’s ‘Water Compositions’ Sparked an Unusual Backlash in the 1960s. Here Are 3 Things You Should Know About the Evocative Series

The water sculptures and other influential works recently went on long-term view at Dia Beacon.

The water sculptures and other influential works recently went on long-term view at Dia Beacon.

Annikka Olsen

American visual artist Senga Nengudi’s work largely defies categorization. Working within the realms of sculpture, installation, and performance, as well as engaging in poetry, curation, and teaching, she is a consummate multi-hyphenate, with each strain of her practice influencing and informing another. Best known for her found object works and documented performances, Nengudi was a significant force within the 1960s American avant-garde, whose work continues to bear relevance to the understanding of 20th-century art today.

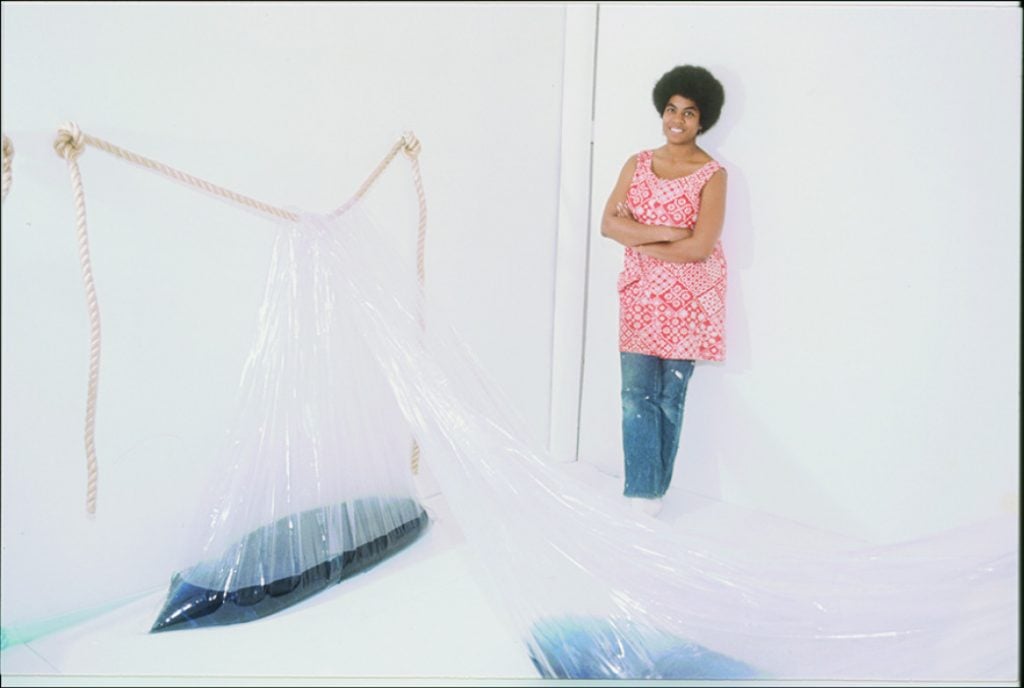

Senga Nengudi. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben Gallery, New York.

Born Sue Irons in Chicago in 1943, Nengudi moved with her mother to Southern California when she was seven years old. She went on to study art and dance at California State University Los Angeles (CSULA), receiving her B.A. in 1966, and went on to earn her M.A. in sculpture in 1971. As a student, she worked as a volunteer at the Watts Towers Art Center in southern Los Angeles and as a teaching assistant at the Pasadena Art Museum (today the Norton Simon Museum). Both experiences contributed to Nengudi’s burgeoning artistic practice, as she was introduced to the work of contemporary artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Allan Kaprow, as well as community-based models of artmaking.

Following the completion of her studies, Nengudi relocated to East Harlem, New York. Throughout her career, Nengudi would frequently move between Los Angeles and New York and the tenor and nuance of each city’s respective art scenes came to shape her artistic identity and development. In 1976, she joined Studio Z, a loose collective of artists based in Los Angeles who, as Nengudi put it, “looked differently at art.” Fellow members included David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Joe Ray, Franklin Parker, Barbara McCullough, and others. The group’s artists maintained individual practices but came together to produce events, concerts, and performances. Following the dissolution of Studio Z in the early 1980s, Nengudi continued to participate in performances across the city with fellow artists.

Back in New York, Nengudi’s work was being shown at the influential Just Above Midtown gallery—notably one of only a few spaces that would exhibit her work at that time. Over the following decades, Nengudi’s art began to gain traction, and her work was shown and her performances staged across the United States and in Europe.

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition (green) (1970). © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation.

In the early 1990s, Nengudi began working as an educator at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, where she taught until her retirement in 2008 (she continues to live in Colorado Springs today). Over the course of her career, she has been the recipient of more than two dozen awards and honors, including being elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2020. Today, at 79 years old, Nengudi continues to be at the forefront of the contemporary art world. Recently, Nengudi was named the 2023 Nasher Prize Laureate—the first Black woman to win the prestigious award—recognizing her more than five-decade career and pioneering practice.

And, earlier this year, Dia Beacon opened a sweeping, long-term exhibition of Nengudi’s work. Curated by Dia’s associate curator Matilde Guidelli-Guidi along with curatorial assistant Emily Markert, the show features both sculptures and installations dated from between 1969 and 2020 (including recent acquisitions to Dia’s permanent collection), highlighting the multifaceted and expansive range of Nengudi’s practice.

Several examples of the artist’s “Water Compositions,” sculptures are featured in the exhibition. These works comprise heat-sealed vinyl forms containing water dyed with food coloring that the artist undertook in the late 1960s and very early 1970s. These water-based pieces are widely considered the artist’s first mature works and reflect the myriad inspirations and influences she worked with to that point—and reveal the early trajectory of her artistic practice.

Marking this significant exhibition and Nengudi’s recent award, we took a closer look at the artist’s early “Water Compositions” and discovered three intriguing facts that bring new light to the important series.

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition (multicolor) (1969/2021). © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation.

While enrolled at CSULA in the 1960s, Nengudi discovered a book on Japanese avant-garde in the school’s library. The book introduced her to post-war Japanese art movements and groups, and she felt a particular resonance with the Gutai Art Association. Initially formed in 1954, Gutai was already an influential force within the global contemporary art world by the time Nengudi discovered it. Dynamic and multidisciplinary, Gutai art exemplified a new approach to artmaking that put focus on the act of creating and the direct engagement with materials (many parallels have been drawn between Gutai and the later Fluxus movement in the West).

Following her graduation, and inspired by the Gutai group, Nengudi spent a year in Tokyo studying Japanese culture at Waseda University. Upon her return, she undertook her first experiments with plastic and water, which resulted in the creation of the “Water Compositions.” These works took various forms: while some were laid across the floor, others were attached to the wall or hung with rope, and some were placed on pedestals. Today, the handling of the water sculptures is exclusively reserved for preparators, but early iterations and presentations of the pedestal-based pieces had an interactive element. Viewers were allowed to gently handle and manipulate the works, making it possible to form a deeper, physical and psychological connection with the materials and their form—an interaction evoking the Gutai ethos

.

Senga Nengudi with Water Composition II (ca. 1970). Courtesy of Tilton Gallery.

Nengudi’s “Water Compositions” embody mid-century American avant-garde conceptualism; at once abstract and visceral, their meaning is interpretive and experiential. At the time of their making, however, most of her contemporaries—specifically fellow Black artists—were working with political art, creating works that directly and often explicitly engaged with prevailing sociopolitical issues. Even in terms of abstract art of the period, many Black artists were creating works that emulated and interpreted the geometries and colors of traditional African textiles. Nengudi’s poetic, mixed media sculptures not only didn’t “fit” with the type of art many expected her to make, but they were considered by some to have openly fallen short of the pressing need to engage with critical and pressing issues faced by the Black community.

Senga Nengudi, detail of Water Composition I (1970/2019). © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation.

During this time, she shared studio space with artist David Hammons in Los Angeles. In a 1986 interview with Hammons for Real Life Magazine he recalled, “This was the sixties. No one would even speak to her because we were all doing political art. She couldn’t relate. She wouldn’t even show around other Black artists because her work was so ‘outrageously’ abstract. Senga came to New York and still no one would deal with her because she wasn’t doing ‘Black Art.’”

Despite initial reserved reactions to the “Water Compositions” from her contemporaries, they were shown in “Eight Afro-Amercans” in 1971 at the Musée Rath in Geneva, Switzerland. By some accounts, this inclusion and the show on the whole—which also featured work by Romare Bearden, Bob Thompson, among others—incurred protests, as it was felt the work featured was not political enough. Critically, however, Nengudi recalls in her 2013 oral history interview for the Archives of American Art that “it was well received.” They were exhibited again in 1977 at the Studio Museum of Harlem in “California Black Artists,” indicating their growing significance within the art historical canon.

Senga Nengudi, Water Composition III (1970/2018). © Senga Nengudi. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy of Dia Art Foundation.

In 1968, design student Charles Prior Hall created the prototype for the first modern waterbed, which he then patented in 1971—and their popularity quickly exploded. Concerned that the “Water Compositions” would be associated with the waterbed (and the mawkish, even tawdry, advertising campaigns that accompanied their dominance in the mattress industry), Nengudi stopped making them. In her oral history, Nengudi said of making her water sculptures, “And I did that until waterbeds came out—[laughs]—and then I said, ‘Well, I can’t do that anymore. Water in plastic has gone commercial. They got waterbeds.’” The conclusion of the “Water Compositions” series led to a multi-year period of reflection and consideration. She slowed her output and focused on further developing her identity as an artist and navigating the art world of each coast.

Senga Nengudi with her work Untitled R.S.V.P as she opens her first major solo exhibition outside the U.S. at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds. Photo: Danny Lawson/PA Images via Getty Images.

Ultimately, she went on to produce her acclaimed “R.S.V.P” series in the mid-1970s, beginning in Los Angeles and premiering in New York, which was influenced by a wide range of Nengudi’s perennial inspirations, including the Japanese avant-garde, Minimalism, textiles, and the human body. Featuring deep-toned pantyhose idiosyncratically knotted and filled with sand, and arranged variously to walls, the works from “R.S.V.P” had a dual artistic function: as site-specific installations and as sites for performance and interaction. Like the “Water Compositions,” the work produced for the “R.S.V.P” series continued Nengudi’s exploration of bodily and anatomical tenets within her work.