Kaleidoscopic landscapes and riotous bursts of flowers are the signatures of Brooklyn-based artist Shara Hughes—scenes she creates entirely from her imagination.

The artist’s third solo show with Zurich’s Galerie Eva Presenhuber, “Day By Day By Day,” opened in June, but she will not have seen it in person by the time it closes in September.

“It’s very strange,” said Hughes. “I travel quite a bit, but I haven’t really gone anywhere. Not even to see family.”

Instead, the artist has spent the past months making only the two-block journey between her Brooklyn studio and her apartment where she lives with her boyfriend, the artist Austin Eddy. She spends her mornings drawing at home, then heads to her studio to exercise (a temporary improvisation), before a long day of studio activity.

That ritual has already proved fruitful. Hughes just opened an exhibition at Parts & Labor gallery in Beacon, New York, which places her new works alongside landscapes by Lois Dodd from the 1960s to the 1980s. In September, Sabine Knust in Munich will open a show of Hughes’s new prints—made mostly in quarantine.

We caught up with Hughes to talk about her favorite studio supplies, living life with another artist, and the one work of art she most wishes she owned.

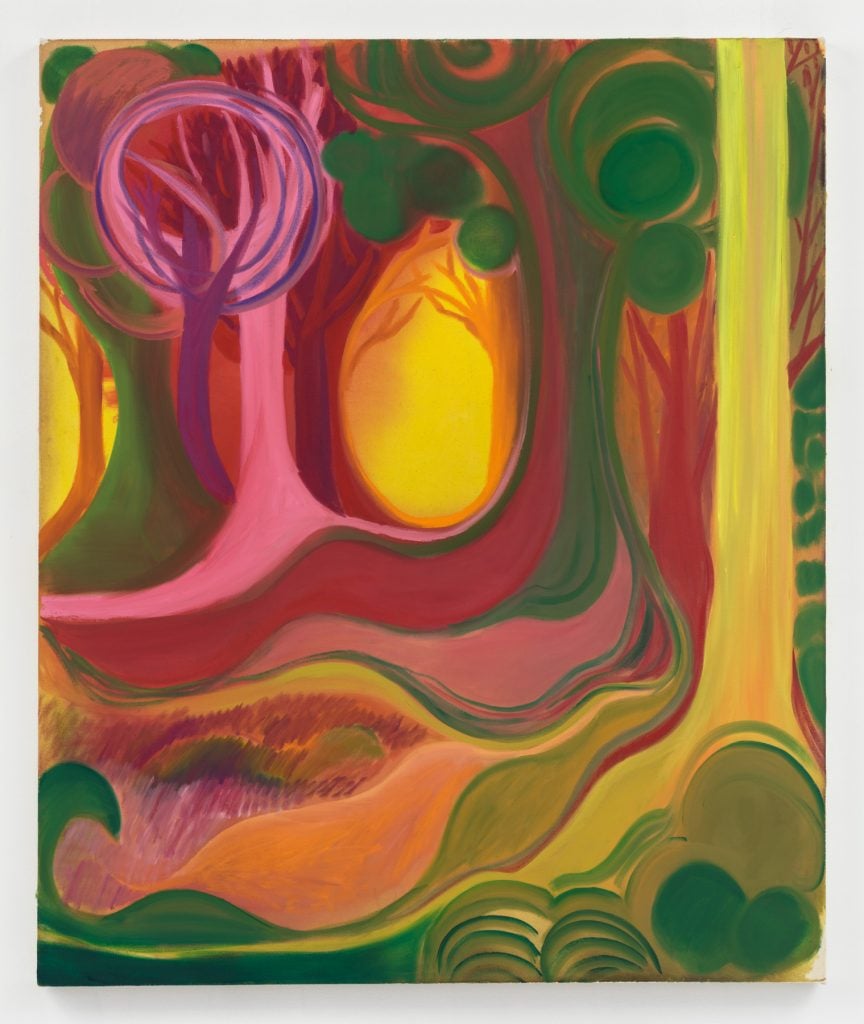

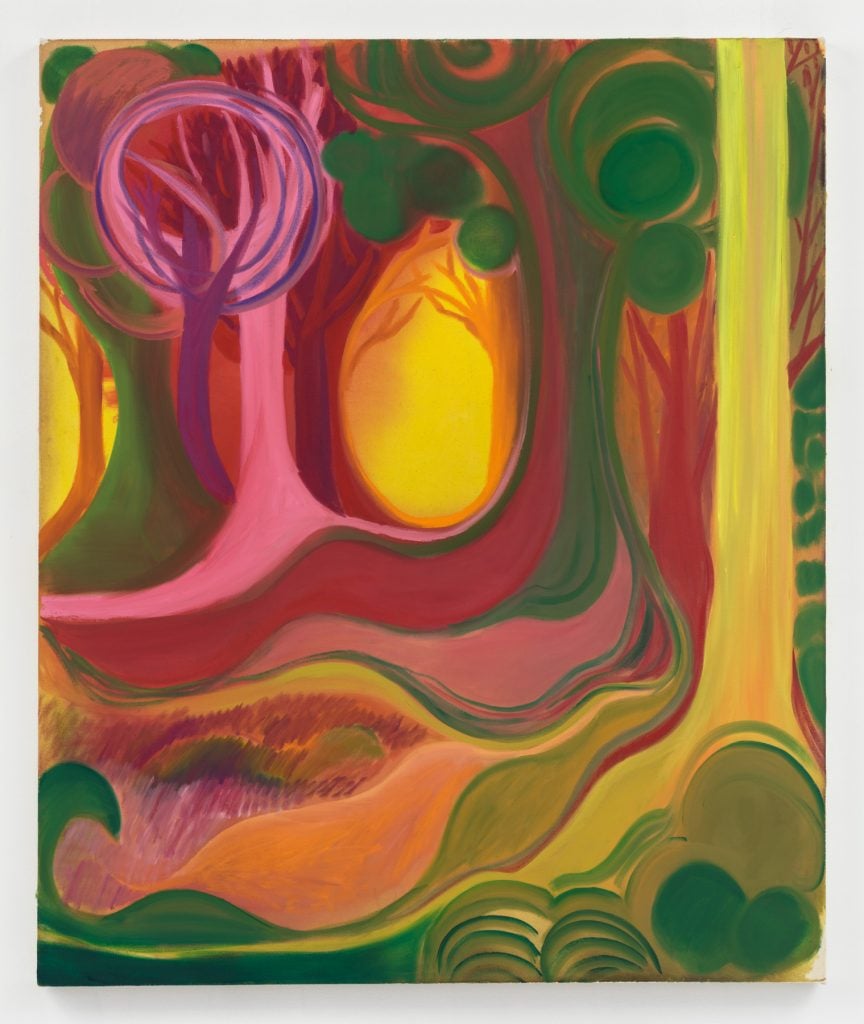

Shara Hughes, Haze (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

Let’s start with the good news that museums are scheduled to reopen at the end of the month. What’s the first museum show you want to see?

The Agnes Pelton show at the Whitney—if it will still be there. I’d been to the Phoenix Museum of Art where the show originated and—while the show wasn’t open at the time—the curators let me come in and see a few works in the back. I didn’t know who Agnes Pelton was and it was a real, “Oh my god, I love it” moment. I’ve been looking forward to the show since.

Unlike say, Vincent Van Gogh or Georgia O’Keeffe, who both made careers painting real-life flowers and landscapes, your imagery comes entirely from your imagination. Why do you find yourself drawn to botanical imagery? What does it offer you?

It just happened. I was tired of making heavily symbolic work and decided I wanted to take the narrative out. The only thing I could think of making, in that case, were some landscapes—ones I thought no one was ever going to see. Instead, landscapes opened a whole new world for me, one that was awesome and exciting.

There’s something very open-ended about the idea of a landscape that appeals to me too. All landscapes are constantly changing, whether it’s the time of day or the temperature or the weather patterns and things growing and dying. The constant state of change created so much possibility.

In another sense, the landscape is so seemingly simple. Everyone knows what a landscape looks like—there is an entire tradition of painting that informs our expectations. I wondered how I could take something that is seemingly so known and make it mine, while still getting all the satisfaction of painting, and the history of painting, in one.

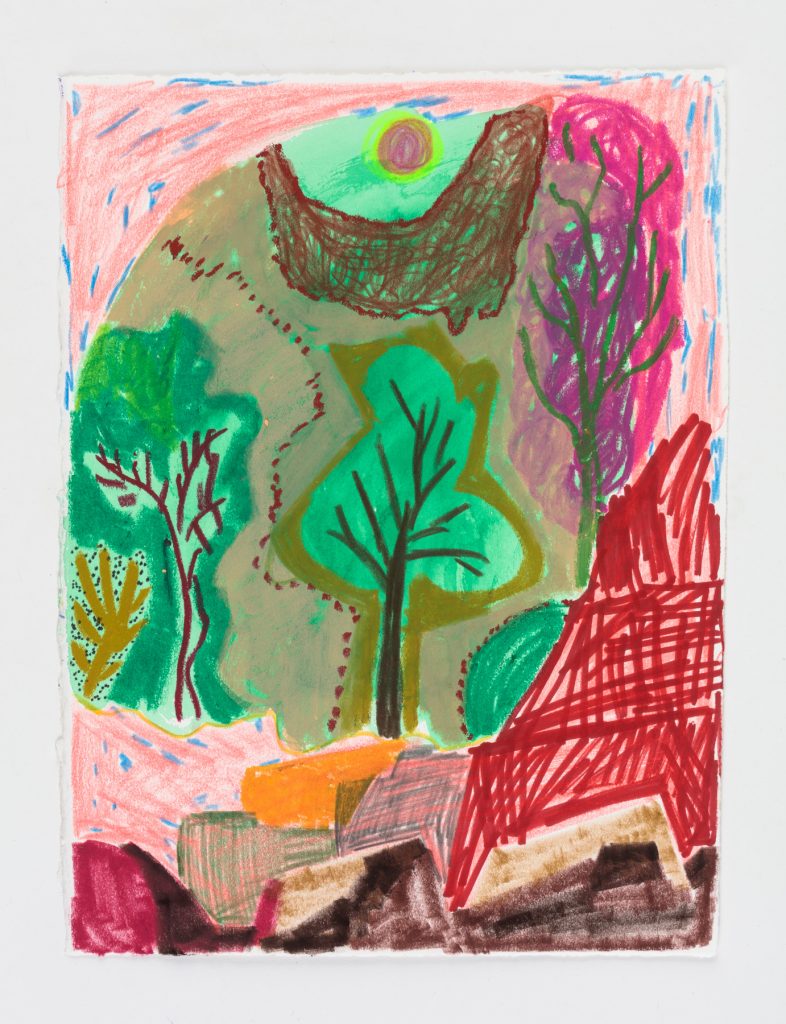

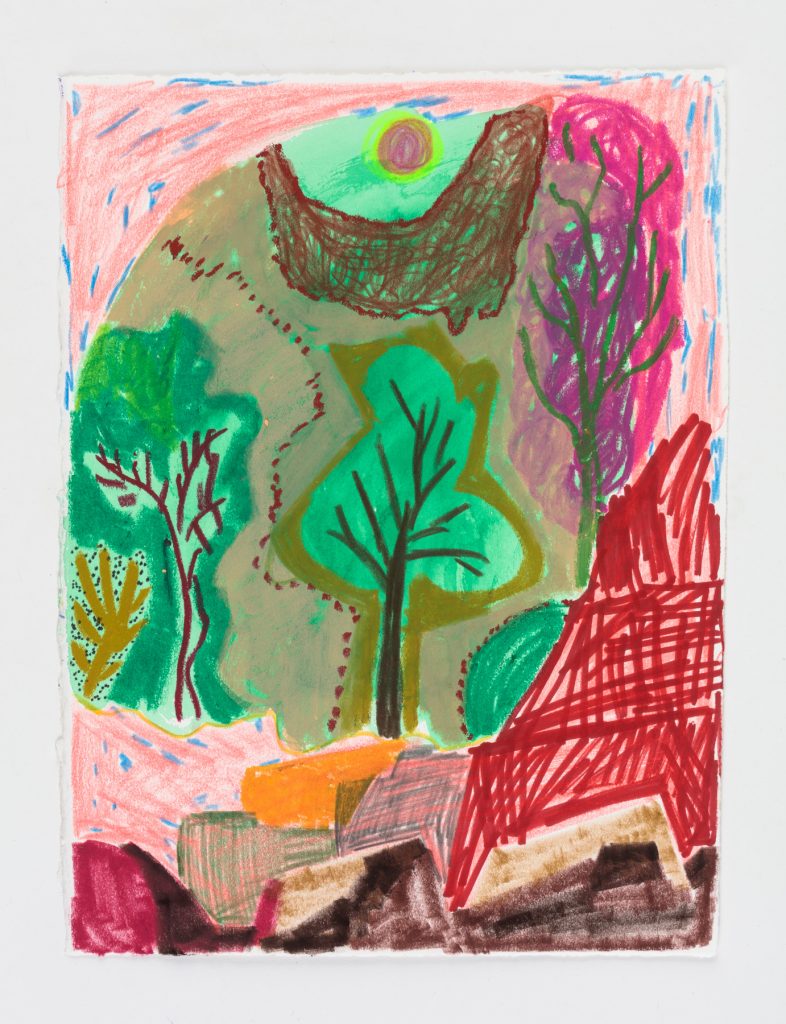

Shara Hughes, Keeping Things In (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

Rather than being pretty or decorative, your flowers can sometimes seem quite menacing and almost alien. Do you have any thoughts about that?

The symbol of the flower is traditionally assumed to be soft and pretty and beautiful—and can be a stand-in for these outdated virtues of womanhood. Typically in painting, you see flowers arranged in a still life in this beautiful way that can be very perfected. I think being able to imagine flowers in a powerful way or a scary way or an ugly way or even a vulnerable way is stretching that kind of one-sided definition into something way more complex, which I like.

Do you have a favorite flower?

No, not really. There was a time when I was interested in poisonous flowers and what they looked like—it turns out they’re beautiful just like most other flowers, so in my work that led me to more thinking of these flowers as the expression of a feeling rather than a real thing. As for real flowers, I wouldn’t even say I know that much about them!

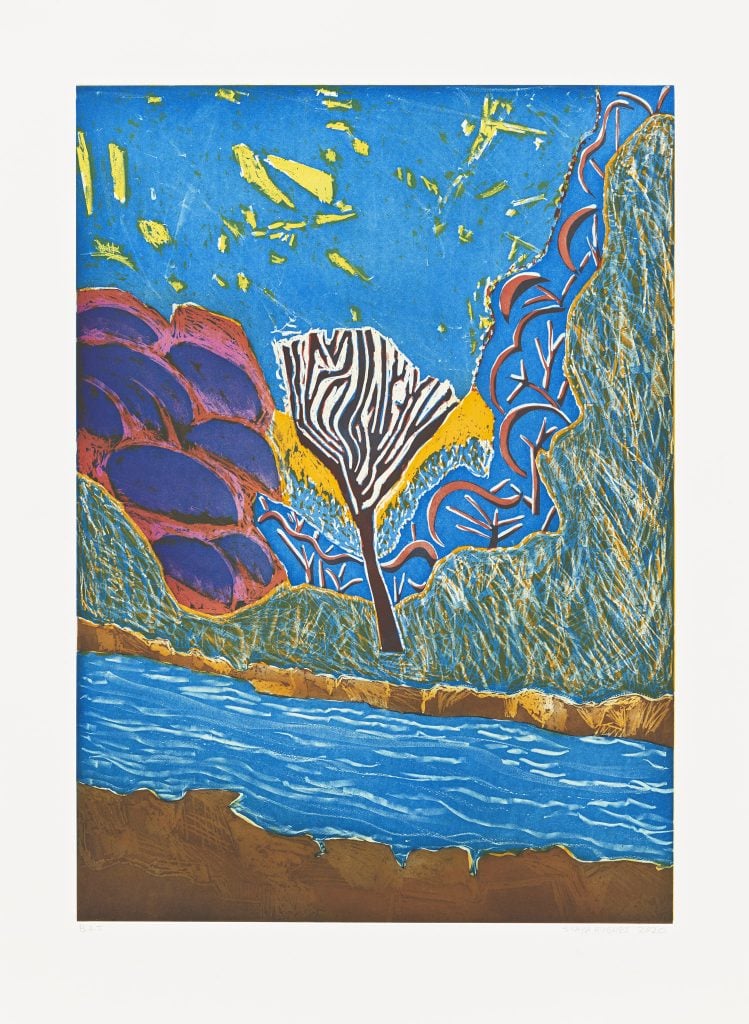

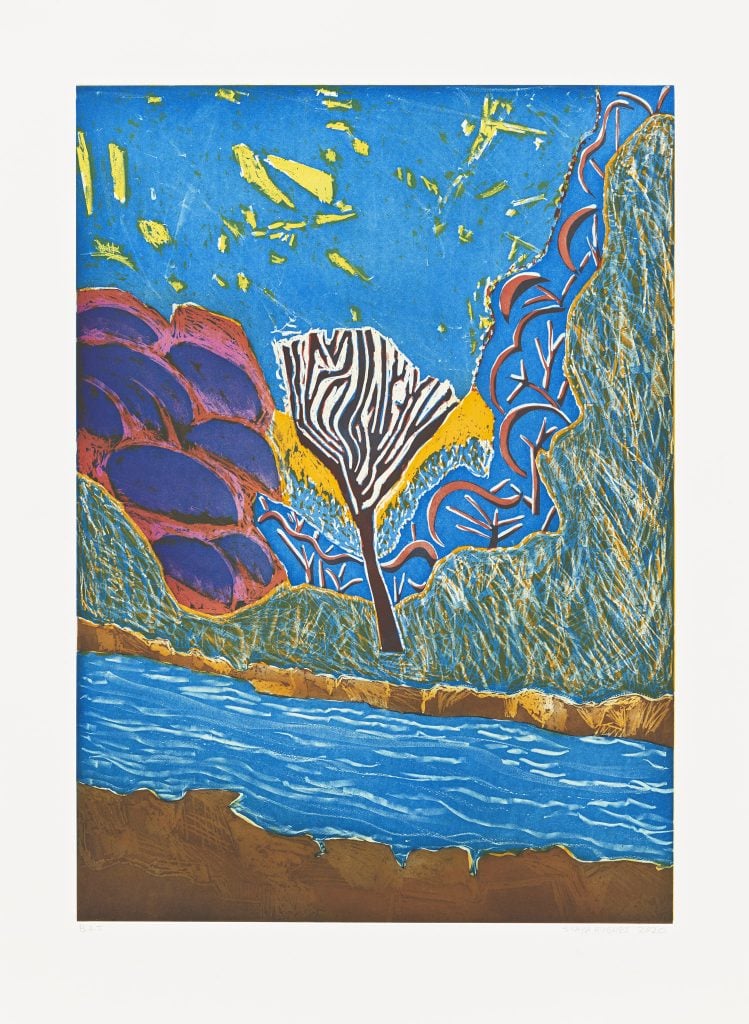

Shara Hughes, Social Distancing (2020). Courtesy of the artist.

How do you know when a work is finished? And what do you think makes a painting good?

I have a painting on my wall right now that I believe I finished six days ago. It stays on the wall until I feel like I can live with it and my eye doesn’t keep getting stuck in one area in a bothersome way. It’s intuition and a sense of not going overboard or not giving away too much and being just enough and still great. I have to trust myself about when to stop.

What makes a painting good is tough. This painting I’m looking at right now is fine, but I think that maybe a painting I made two weeks ago might be better. I don’t necessarily know why. Maybe it’s the color, or maybe the composition is too easy, or too complicated.

When you do something every single day, like exercising, you become more attuned. With painting, your sense of color gets heightened and the sense of composition gets really specific. It turns into something that’s so natural that it’s hard to explain, but you just know. That said, sometimes other people see things I don’t—there are paintings that I don’t think are that special and my boyfriend will be like, “Oh that one’s really great.” So with all things, we can be our best and worst critic.

Your boyfriend is also an artist. Do you think that affects your practice if at all?

I never really wanted to date an artist because I think we can be kind of complicated. But Austin and I are the exact same person in so many ways. We’re both crazy workaholics and that works out well for both of us. Even when we are traveling we have to bring our supplies and are drawing every day. I feel like with somebody else it could be an annoyance, like why are you always at the studio? And it’s fun to have somebody to go with you to all the things you love.

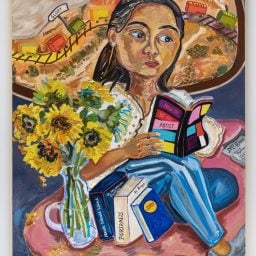

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio (1911). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art

Do you have a favorite object in your studio?

I have so many supplies and there’s nothing I couldn’t do without but there are certain paintbrushes that I have that are so bent and the hair is all furry. I use these for specific kinds of areas. You can’t buy a brush like that because it’s basically trash—but sometimes I know how to use those trash tools to my advantage. So you could say I have a collection of really nice brushes to really not so nice ones and that’s good because I can play all those notes—that range is probably my most prized studio possession.

Let’s end on my favorite question: If you could own any work of art, no limitations, what would it be and why?

I think about this a lot actually and had a big discussion with some of my other painter friends about this. For me, it’s Matisse’s Red Studio. It might be predictable, but I can’t stop thinking about that one—then there’s none other. There are a million amazing paintings that I would live with, too, but that’s my number one.