There is an overwhelming amount of shows across Venice to see this week—some 30 official collateral events are on view, dozens of galleries have brought their own exhibitions, and there are a bunch of private museum foundation shows to see.

Our team placed bets about what we thought would be exciting to see in the lagoon, but sometimes those expectations did not match up with reality. Here are our honest reviews.

Pierre Huyghe’s “Liminal” at Punta della Dogana

Pierre Huyghe Liminal (temporary title) (2024–ongoing). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Marian Goodman Gallery, Hauser & Wirth, Esther Schipper, and TARO NASU © Pierre Huyghe, by SIAE 2023

Expectation: Before it was one of the biggest trends in the art world, the French conceptual artist Pierre Huyghe was pushing the boundaries of fiction and reality. I was bowled over in 2014 when I stumbled into his exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in 2013, which saw the institution transformed: a dog with a pink leg roamed around a landscape made of a drywall; a hermit crab lurked in a foggy aquarium dragging his home, which was a Brancusi-like head. These live situations, where sculptures move and breathe and where representation in film bleeds into the real space of installation, arouses questions about humanity and the natural versus the synthetic. It was this trajectory that eventually brought Huyghe to the realms of artificial intelligence and machine learning, which are major themes in his new exhibition “Liminal” at Punta della Dogana. In his largest institutional solo show to date, a new film is changing and being edited in real-time by A.I. as performers circulate the institution donning golden LED screen masks.

Reality: Amid all the decorative opulence of Venice, and off the back of all the very colorful art in the Giardini and Arsenale, the minimalism of “Liminal” was striking. You enter into the Punta della Dogana and are immediately immersed in near total darkness until your eyes adjust. That is just one of a few subtle interventions that have a huge effect, including gritty dirt that is suddenly under your feet in another gallery space.

But Huyghe’s brand of minimalism here is also maximal—his video works are playing on the largest screens I have seen in years. The size of the show and the expanses of distance between the works is a flex in its own right and a testament to just how much real estate an artist of his stature can be given.

Does he use it well? For the most part, yes, but the entire show begins to feel like a mausoleum that is visiting us from a distant future. That includes the aspect of the show I loved the least: performers who slowly emerge from dark corners with gimmicky golden masks on that look like they were pulled out of Netflix’s “3 Body Problem.” The same magic that I found in other shows by Huyghe is not there for me this round, but I will always come back for more.

Rating: ★★★☆☆

–Kate Brown

“The Spirits of Maritime Crossing” at Palazzo Smith Mangilli Valmarana

Jompet Kuswidananto, Terang Boelan (Moonshine) (2022), at “The Spirits of Maritime Crossing,” at Palazzo Smith Mangilli Valmarana. The work is in the collection of Bangkok Art Biennale Foundation. Courtesy the artist and Bangkok Art Biennale.

Expectation: While the main exhibition at the Arsenale aims to shine a spotlight on the Global South and artists who were previously overlooked under the banner of “Foreigners Everywhere,” there’s still a large chunk of artists from Southeast Asia missing, according to Apinan Poshyananda, artistic director of the Bangkok Art Biennale. This exhibition, an official collateral event presented by the Bangkok Art Biennale Foundation and co-hosted by One Bangkok, aims to fill the gap.

The exhibition features 40 works by 15 artists from across Southeast Asian including Cambodia, Laos, and Indonesia; most of the countries represented do not have pavilions. “As the oldest and most grandiose international event, the Venice Biennale continues to take center stage despite criticism of its outdated nation-based platform and the inherent power structure of rich and poor pavilions,” Poshyananda said in an earlier interview. He said this exhibition “can be a new model for future presentation that shifts away from national format and restrictive government control.”

Reality: It is exciting to see the presentation of Southeast Asian artists in Venice, especially when most of them do not have a consistent presence in the national pavilions for financial and political reasons. At the same time, fitting these artists’ works in the historic Palazzo Smith Mangilli Valmarana seemed challenging.

As such, some of the original power of a few works have inevitably been discounted due to the limitation of the architectural structure, such as Thai artist Jakkai Siributr’s There’s no Place (2020), an elaborate installation consisting of embroidery that thrived in an outdoor open space. But the bulk of works on view are nonetheless intriguing, and great examples of the diversity and versatility of Southeast Asian contemporary art scene. A particular highlight was the symbolic mixed media boxes from the series Jesus is condemned to death (2023), depicting the journey of Jesus carrying the cross by the Filipino artist Alwin Reamillo and the humorous and thought-provoking video works by the Bangkok-born Kawita Vatanajyankur, who turns her body into a toilet brush in The Toilet (2020).

The titular video work (“The Spirits of Maritime Crossing” is also the name of a collaborative film by Poshyananda and Marina Abramović) did feel a little out of place. The works by Southeast Asian artists are strong enough to be the stars of the show, not overshadowed by an international name that people are already familiar with. Nevertheless, it is still an exhibition well worth seeing if you are in Venice.

Rating: ★★★☆☆

–Vivienne Chow

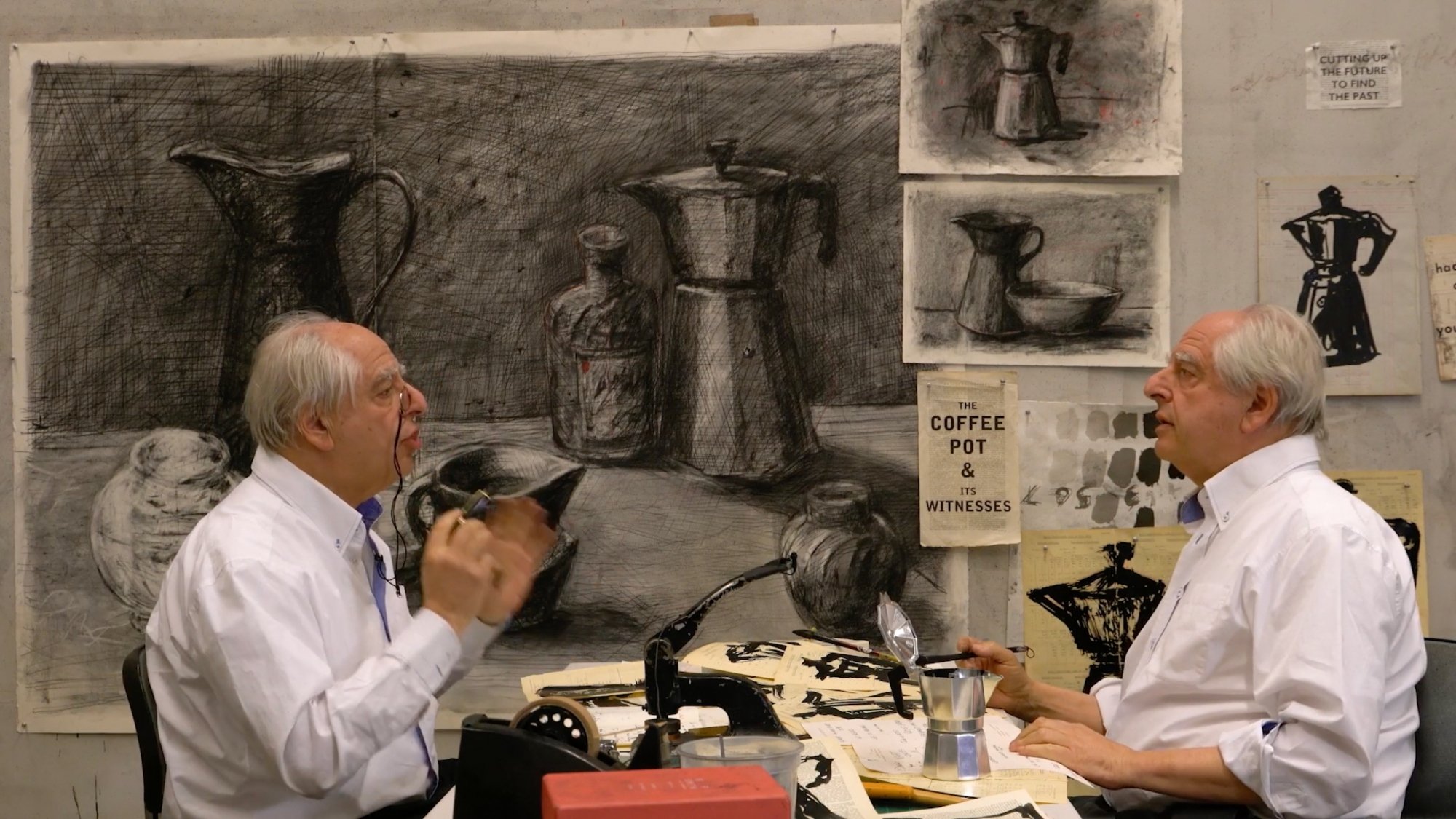

“William Kentridge: Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot” at the Arsenale Institute for Politics of Representation

“Self-portrait as a coffee pot.” Installation views. ‘William Kentridge. Self-Portrait as a Coffee-Pot‘, Arsenale Institute for Politics or Representation, Venice. ©️ William Kentridge. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2024. Courtesy the artist, Goodman Gallery, Galleria Lia Rumma and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

Expectation: The South African artist debuts a new series of 30 minute films made during lockdown that explores how rumination and conversation evolves into creative acts within the apparent confines of the studio. In some videos Kentridge often appears deep in conversation with himself, taking on some of life’s eternal themes like utopia, optimism, and history. Shown across two screens, the videos are housed on the ground floor within a custom immersive installation that brings the studio environment to Venice. On the top floor, in an apartment that once belonged to the German painter Oskar Schlemmer, the films are presented as one might watch them in the domestic sphere: on a laptop in the kitchen or on a TV in the bedroom.

“His is an elegiac yet humorous art that explores the possibilities of poetry in contemporary society,” said the show’s curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. It “provides an acerbic commentary on our society, while proposing a way of seeing life as a continuous process of change and uncertainty rather than as a controlled world of facts.”

Reality: Woven through with anecdote, observation, philosophical musings, and skits, the films feel genuinely expansive in their ambition, so much so that it might strike the viewer as a bit unusual—so often artists instead endeavor to define and contain the conceptual possibilities of their projects. Christov-Bakargiev’s curation is precise yet creates an impression of creative spontaneity that feels quintessentially Kentridge: the walls are curtained in newspaper clippings and there are smears of black paint and hastily scrawled notes on scraps of paper. A delightful set of handmade sculptures bring signature drawings like the coffee pot to life in three-dimensional form.

Speaking at the show, Kentridge emphasized the studio as “a machine for working but also a subject,” which it often historically was. In this age of digital nomads, sites of creativity are often a bit sleeker and more portable. “This is very much an argument about the dirtiness and grittiness of paper, ink, charcoal, and human gesture, as opposed to just the action of your knuckles on a keyboard,” he said. “It’s either your wrist or elbow or shoulder or whole body in movement: both making but also a performance.”

“These films are about the possibility of physical making as a way of thinking,” he added, “thinking in cardboard, thinking in ink, think in charcoal, allowing the hands and the material to lead the thinking. Ideas can be generated in the activity of making. The meaning comes at the end of the work, in the gap between the assumption of knowing and making the work. What actually comes out is who you are.”

Rating: ★★★★★

–Jo Lawson-Tancred

Dread Scott’s “The All African People’s Consulate” at Castello Gallery

Dread Scott, All African People’s Consulate (detail of participant with passport), 2024. Participatory installation. Courtesy of the artist and Cristin Tierney Gallery, New York.

Expectation: Conceptual artist Dread Scott is interested in how one of the defining experiences of immigration can be reimagined to be more inclusive. In this new exhibition, he aims to invert the pinnacle of rigid, exclusionary nation-state bureaucracy—otherwise known as passport control—by making it a welcoming and collaborative process. Visitors to the consulate will interview with staff about their relationship to Africa. For those of African descent, the staff will offer them a personalized passport that facilitates their citizenship in a futurist, globalist community; others receive a visitor’s visa.

The project echoes the Afrofuturist call for a union that draws together all Black people of Africa and its diaspora. But Scott takes this one step further and ultimately makes it a reality. In issuing his own passports at The All African People’s Consulate, he draws into existence a new state, one not dependent on land, exploitation, or violence, as most others have been. It might not be recognized by certain governments, but neither is Palestine and it and its people are no less real.

Like in his Slave Rebellion Reenactment, an ongoing project started in 2014 that was filmed in 2019 by John Akomfrah, who represents the U.K. at this year’s biennial, Scott’s consulate concept re-envisions a world where Black and other marginalized people have the freedom of movement and right to exist that is automatically afforded to so many others (many of whom have white skin). Nevertheless, it’s hard to imagine that a consulate, even a revolutionary one like Scott’s, could be exciting and few details about the performance work and its environs were given in advance.

Reality: On the opening day of the exhibition, a speaker set up outside of the “office” was blasting Afrobeats and the vibe inside the space was buoyed by some snacks and fizz. I doubt that this energy will be consistent throughout the run of the exhibition, so be prepared to show up to what is essentially just a waiting room. Visitors will need to participate in the bureaucracy to understand the work, which ultimately is a strength of the artist’s concept.

After checking in for an interview for a visa at the front desk, I loitered for about 30 minutes until my name was called and I was shown into a side room with a desk, a chair, and an inkjet printer. I was subject to a brief interview about my relationship to Africa, which, as a white citizen of the United States, is fraught: I have obviously structurally benefitted from the historical exploitation of the continent’s resources and people that undergirds everyday life in America. But the interview was conversational, not intimidating, and after a quick passport photograph, I had a freshly minted visa in my hands. Having also just renewed my U.K. visa, I can tell you that the consulate’s congeniality and expediency is a wonder.

Rating: ★★★★☆

–Margaret Carrigan

“Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge” at Peggy Guggenheim Collection

Philippe Halsman, Jean Cocteau New York, USA. 1949 © Philippe Halsman / Magnum Photos.

Expectation: This retrospective exhibition of Jean Cocteau, the renowned artist, writer, filmmaker, and multifaceted figure central to the French twentieth-century art scene, is not an official collateral event, yet what would Venice be without a visit to Peggy Guggenheim’s storied collection?

Comprising over 150 works spanning various mediums including drawings, graphics, jewelry, tapestries, historical documents, books, magazines, photographs, documentaries, and films, the exhibition promises to showcase Cocteau’s remarkable versatility as an artistic “juggler.”

The exhibition’s titular “revenge,” appears to allude to the criticism Cocteau faced during his lifetime for what some viewed as over-extension across various pursuits. However, curator Kenneth E. Silver remarks in his exhibition text that contemporary artists are now expected to demonstrate such multihyphenate cultural adaptability. Considering also Cocteau’s modern sensibility in being open about his homosexuality, and the contemporary resonance of his public struggle with opium addiction, Silver suggests dryly: “Perhaps the world has finally caught up with Jean Cocteau.”

Reality: While there’s no doubt that Cocteau’s fascinating life and work deserves more recognition, the exhibition feels somewhat slight. Discoveries included an anonymous book of erotic cartoons detailing Cocteau’s love for men, and I added the 1932 film The Blood of a Poet—starring Lee Miller as a classical statue—to my watch list. Aside from that, some of the ephemera, and examples of his collaborations with brands like Schiaparelli felt like filler, and the setting isn’t the comfiest one in which to watch the entirety of La Belle et La Bête. In the panorama of what’s on view in Venice, I’d vote skip.

Rating: ★★☆☆☆

–Naomi Rea

“Boris Lurie: Life With The Dead” at Scuola Grande San Giovanni Evangelista

Boris Lurie, Three Women (1957). Photo: © Boris Lurie Art Foundation.

Expectation: Born in the Soviet Union in 1924 to a Jewish family, Lurie lost his sister, mother, and grandmother to the Holocaust but managed to survive imprisonment in a concentration camp. By the time he settled in New York in 1946, he found himself living amid the memories of the dead. This unique perspective pushed him towards making subversive political work and he remained on the fringes of an art world obsessed with consumerism and conceptualism.

Lurie always brought our attention back to the darker sides of humanity with his anti-market movement “NO!art,” co-founded in the 1960s. He was boldly unafraid to shock audiences, making collages, sculptures, and paintings filled with explicit references to Nazism, including the use of swastikas and yellow “Jude” stars. The critic Harold Rosenberg once described NO!art’s shows as “Pop with venom added.”

Though he was a regular on the New York scene, Lurie’s work has had particular resonance in Germany. The Center for Persecuted Arts in the German town of Soligen is dedicated to artists who were historically suppressed by the Nazis or the GDR (East Germany). It has organized this exhibition to celebrate the centenary of Lurie’s birth.

Reality: These dense collages, which mix painting, magazine clippings, and found objects, pack some punch, alternating in surprising ways between dark humor and uncomfortable examinations of brutality. Or both at once, as in one archival photograph of a frail Holocaust victim in a concentration camp that is casually labelled From a happening, 1945, by Adolf Hitler (1969). Though the intention is to protest an increasingly commercial West that was moving on too quickly from the horrors of World War 2, references to Pop Art and “happenings” skewer the midcentury New York art scene more obviously than society at large. Some works took aim at political enemies within America and expressed outrage over what he saw as the government’s complicity in the murder of Patrice Lumumba, the first freely elected president of the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1963.

Lurie’s warnings about the tempting trap of forgetting history’s hardest lessons in favor of fun and fanciful distractions are timeless but some of his more moralizing reprimands are not. The gratuitous overuse of pornographic images of women, allegedly to condemn their exploitation, rings false and feels instead like its own form of exploitation and chastisement. Nonetheless, the show is impeccably well put together and I was happy to learn about the NO!art movement because it is always amusing to watch obscure art world infighting.

Rating: ★★★☆☆

–Jo Lawson-Tancred

“Breasts” at ACP Palazzo Franchetti

Laure Prouvost, The Hidden Paintings Grandma Improved, In Deepth © Laure Prouvost Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Expectation: The group show curated by Carolina Pasti has great ingredients on paper: works by artists including Louise Bourgeois, de Chirico, Cindy Sherman and many more, all loosely united in their depictions of the titular subject.

Reality: Yes, it’s sponsored by fast fashion lingerie brand Intimissimi, but I came in with the most open mind and best of intentions. According to the press release, “the presentation investigates how breasts act as a catalyst to discuss socio-political realities, challenge historical traditions and express personal and collective identities,”—and I mean, who doesn’t love boobs? But wow, this show is shockingly bad. The entrance’s long red hallway of boob-shaped ceiling lights, a contribution by London-based designers Buchanan Studio is titled—I kid you not—“Booby Trap” and it sets the tone.

From there each room is loosely tied to an alleged theme; whatever those might be, the first room was tasteful nudes of white women (the Cindy Sherman was a highlight, de Chirico’s treacly portrait of what looks like Martha Stewart was a low); the second room was a vitrine of small sculptures; the third room was photographic nudes of not white women; and the third room that we’ll call a wildcard of no discernible theme included Chloe Wise, Laure Prouvost, fiber art, and my own sinking disappointment.

The one saving grace is that it’s sort of for a good cause—thirty percent of catalog proceeds go to cancer research at Fondazione IEO-MONZINO—but you’d be better off sending donations directly.

Rating: ★★☆☆☆

–Janelle Zara

Christoph Büchel’s “Monte di Pietà” at the Fondazione Prada

Christopher Büchel, The Diamond Maker (2022-). Photo courtesy of Fondazione Prada.

Expectation: The Swiss provocateur is no stranger to courting controversy at Venice. In 2019, he debuted Barca Nostra (Our Boat), the recovered wreck of a barge that sank in the Mediterranean in 2015, killing 1,100 migrants trying to make their way to Sicily. Taboo-breaking work is generally celebrated in the art world, but this divisive piece was seen by many as a step too far. Members of the art world described the work as “haunting” and “absolutely vile.”

Thankfully, Büchel’s latest venture is more diamanté than disquieting. Hosted at Palazzo Ca’ Corner della Regina, “Monte di Pietà” rifts on one of the venue’s earlier functions as a pawnshop with reasonable interest rates that served as an antidote to loan sharks between 1834 and 1969. Inspired, Büchel has decided to explore how debt continues to be used as a means of power and suppression.

At the show’s center is The Diamond Maker, an ongoing project since 2022 that takes aim at the art market’s materialistic approach to constructing value. Büchel has been making lab-grown diamonds by applying heat and high pressure to extracts of organic matter from his unsold artworks and his own feces. That surely won’t put off the avaricious art world, which is lured in less by shiny surfaces than the slightest whiff of anything that claims to be transgressive.

Reality: The show did not open on time in vernissage week so it remains shrouded in mystery. One thing for certain, Büchel’s name has made much less of a splash in Venice than it managed to in previous years.

Rating: ?

–Jo Lawson-Tancred