Art World

Here Are 6 Things You Need to Know Going Into the Venice Biennale

Get up to speed fast on the biggest news stories about the biennial so far.

Get up to speed fast on the biggest news stories about the biennial so far.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

There has been no shortage of news in the lead-up to the 60th Venice Biennale, where art and politics have perhaps never felt more closely entwined. Organized for the first time by a curator from the Global South, the event will spotlight the experiences of marginalized people and underrepresented groups who have historically been left out of the predominantly white, Western art canon. It opens against a backdrop of ongoing geopolitical tension amid wars in Gaza and Ukraine, and during a year of more than 64 national political elections around the world. The Biennale Foundation itself has just installed a new president, which could change the shape of the event for years to come.

As the much-anticipated vernissage week arrives and the art world descends upon Venice, we’ve compiled a handy guide to the biennial’s biggest news and politics stories so far to get you up to speed before arriving in La Serenissima.

This year’s edition of the Venice Biennale is curated by Adriano Pedrosa, the artistic director of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo. He is both first Latin American and first curator from the Southern Hemisphere to organize the event. Speaking on Artnet’s The Art Angle podcast, Pedrosa said he feels a sense of “huge responsibility” to curate the show “strategically.”

“What I’m trying to do is really a speculative curatorial exercise,” he said. “It’s a draft, it’s an essay, it’s a provocation. I do feel that Venice gives us this opportunity to propose something quite ambitious.”

Adriano Pedrosa. Photo: Courtesy of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand.

Pedrosa’s chosen theme for the main exhibition, “Foreigners Everywhere,” spotlights those who are typically considered to be outsiders living on the margins of society. It will feature an impressive 331 artists, with the Global South having a particularly strong presence compared to past years. Pedrosa is also keen to platform the work of Indigenous artists, overlooked modernists from outside the Western tradition, queer artists, and artists from the Italian Diaspora.

Our data reveals that Pedrosa is also putting the spotlight on historical artists who were overlooked in their lifetimes. Additionally, the exhibition includes three times as many Asian artists and artists of Asian heritage compared with the 2022 edition, as well as a growing number of official and unofficial collateral events surveying an increasingly global Asia.

Of the long list of 87 nations headed to Venice, first-time exhibitors include Ethiopia, Timor-Leste, Tanzania, and the Republic of Benin. Morocco had planned to participate for the first time but its pavilion was unfortunately cancelled soon after it abruptly dropped its selected artists in January.

In a bumper year of elections around the world, many with questionable presidential candidates, the Venice Biennale has seen its own new president installed: Pietrangelo Buttafuoco. “How exciting, what are his credentials?,” you might ask. After all, this is one of the most important leadership roles on the international art scene. His celebrated predecessor, Roberto Cicutto, had previously been CEO of the prestigious Istituto Luce-Cinecittà and had been tapped by Italy’s formerly center-left cabinet to be the biennale’s president in 2020; he was forced to step down last month, at the end of his first term, following the appointment of Buttafuoco.

Comparatively, Buttafuoco’s cultural CV seems a little lacking: he did a stint directing a regional theatre in Catania in 2007. He does, however, have extensive experience as a right-wing journalist with ties to neofascist organizations and, last year, he published a gushing biography of the late Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s scandal-plagued conservative prime minister during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Pietrangelo Buttafuoco is an Italian journalist, writer, television host and commentator. Photo: Leonardo Cendamo/Getty Images.

Incidentally, Buttafuoco is friends with Italy’s culture minister, Gennaro Sangiuliano, and has publicly supported the current far-right prime minister Giorgia Meloni, stating last year: “Every morning I say a prayer that she will make it.” His appointment to the Venice Biennale presidency was highly praised by Meloni’s government. One member, Raffaele Sperazon, proclaimed: “Another glass ceiling has been broken. Often, the Biennale Foundation has been considered by the left as a fiefdom in which to place friends and acolytes. Buttafuoco, finally, affirms a change that the Meloni government wants to imprint in every cultural and social center of the nation.”

Will Buttafuoco have any sway over the curatorial direction of the Biennale? He’s only just joined so the implications of his premiership have yet to play out, but it remains to be seen whether an inclusive theme like “Foreigners Everywhere” would be permitted at the 61st edition of the Venice Biennale in 2026.

One clue to how a country’s politics might influence its exhibitions was the original proposal for Poland’s pavilion, conceived of while the country was ruled by right-wing populist party Law and Justice. The series of paintings by Ignacy Czwartos, titled “Polish Exercises in the Tragedy of the World: Between Germany and Russia,” featured dark ruminations on the various ways in which Poland has been historically mistreated by its neighboring countries. Some critics believed that this preoccupation with the painful past placed too much focus on nationalistic grudges. Karolina Plinta branded the concept “an anti-European manifesto.”

Installation view of “The Painter Was Kneeling When Painting” exhibition by Ignacy Cwartos at Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw, Poland. Photo: Juliusz Sokołowski, courtesy of Zachęta National Gallery of Art.

Shortly after the country’s new centrist prime minister Donald Tusk took office in October, the ministry of culture decided to submit a more timely and altruistic exhibition concept. The pavilion will now showcase Repeat After Me, a performance video by the Ukrainian art collective Open Group that spotlights the experiences of Ukrainian refugees. Czwartos’s plans, meanwhile, will not be thwarted. His off-site exhibition “Polonia Uncensored” is set to open near to the Giardini.

There are a few more cross-border collaborations on view this year that underscore the fraught nature of national pavilions. Denmark’s pavilion will host a presentation by the Indigenous Greenlandic artist Inuuteq Storch. Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark but won home rule in 1979. South Korean curator Sook-Kyung Lee is the first non-Japanese national to be invited to curate Japan’s pavilion this year. Meanwhile Koo Jeong A, the artist representing Korea, told Frieze, that her project Odorama Cities “is a response to the segregation represented by the national pavilions in the Giardini.”

Even Russia is initiating some international agreements. As Putin’s war on Ukraine wages on, Russia’s stately pavilion in the Giardini was set to sit empty for the second edition in a row. Realizing that it was wasting some hot real estate, the Kremlin has instead lent it to the Plurinational State of Bolivia.

The closed pavilion of Russia pictured at the 59th Venice Biennale. Photo: James Arthur Gekiere/ Belga Mag/AFP via Getty Images.

In 2022, the South American country’s pavilion was hosted at a small off-site venue Artspace4rent. This Russian pavilion, however, should provide ample room for its exhibition “Qhip Nayr Uñtasis Sarnaqapxañani,” or “Looking at the future-past, we are treading forward,” a survey of some 25 artists from Bolivia and other Latin American countries.

Russia and Bolivia are no strangers to striking deals. Late last year, Russia’s Uranium One Group signed a highly sought-after $450 million contract with Bolivia to gain access to its 23 million metric tons of lithium reserves. The valuable resource is used to make lithium-ion batteries, which are in particularly high demand for the production of electric vehicles.

Not every country currently involved in a serious military conflict will be ducking out of this year’s show. Israel’s participation has provoked anger across the international arts community, with over 23,000 artists, curators, and writers signing the Art Not Genocide Alliance (ANGA)’s petition for the country to be excluded in light of its ongoing attacks on Gaza that have killed more than 30,000 Palestinians. Among the signatories are Nan Goldin, recent Turner Prize-winner Jesse Darling, and Adam Broomberg, the photographer participating in one of this year’s official collateral events as part of Artists and Allies of Hebron.

Israel will present a “Fertility Pavilion” reflecting on contemporary motherhood, courtesy of artist Ruth Patir. The ANGA petition noted that “Israel has murdered more than 12,000 children and destroyed access to reproductive care and medical facilities. As a result, Palestinian women have C-sections without anesthetic and give birth in the street.”

Ruth Patir. Photo: Goni Riskin.

Shortly after the petition was published, Italy’s culture minister Gennaro Sangiuliano ruled out the possibility of barring Israel from the Biennale. “Israel not only has the right to express its art, but it has the duty to bear witness to its people precisely at a time like this when it has been attacked in cold blood by merciless terrorists,” he said. “My deepest solidarity and closeness goes to the State of Israel, its artists, and all its citizens.”

The Venice Biennale’s organizers said in an email, “it’s important to emphasize that, according to the [Biennale’s official] procedures, the decision to participate or not lies with the countries,” noting that Russia opted to withdrawn from the 59th edition in 2022. Shortly after October 7, Patir and the exhibition’s two curators told ARTnews that they were “left stunned and horrified” by both Hamas’ actions and the “escalating humanitarian crisis in Gaza.” They added, “we cling to the belief that there has to be a pocket for art, for free expression and creation amidst everything that’s happening.”

ANGA is now calling on the Biennale’s attendees to boycott Israel’s pavilion. The Glasgow-based artists Cade & Macaskill’s show “The Making of Pinocchio” had been selected as part of the theater program but they have since withdrawn their work in protest of Israel’s participation.

Palestine, meanwhile, has never had a national pavilion at the Venice Biennale because, like the majority of E.U. countries, Italy does not recognize it as a sovereign state. The closest thing Palestine will get to official representation in Venice this year is “South West Bank,” a group exhibition co-organized by the Artists and Allies of Hebron and the Bethlehem-based Dar Jacir for Art and Research. Among the Palestinian artists included are some familiar names like Emily Jacir and Jumana Manna. It is one of 30 official collateral events chosen by this edition’s curator Adriano Pedrosa.

One of the participating artists, Dima Srouji, stressed that “the theme of the show is not a response to genocide, it’s a continuation of our practice that we’ve all been doing for years. We’ve been living in apartheid for 75 years and the art world in Palestine has always responded to occupation. The only difference for us is the scale of atrocity.”

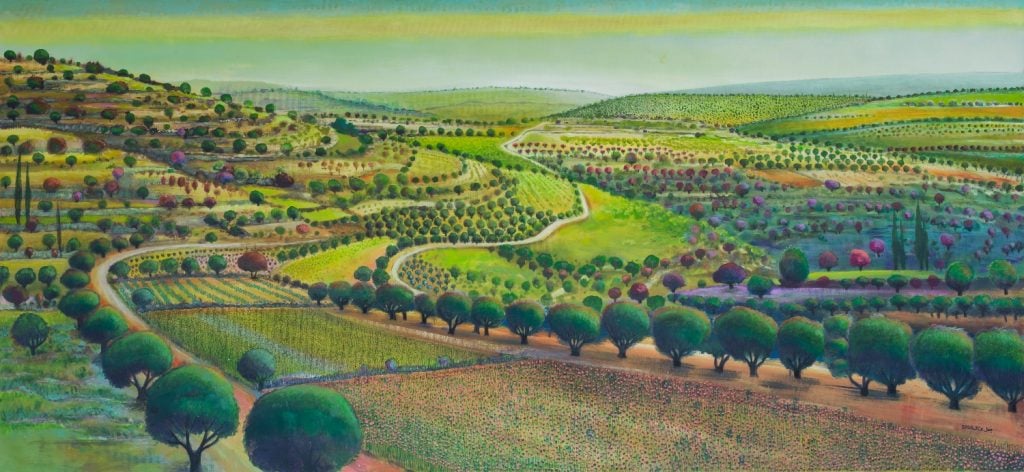

Nabil Anani, In Pursuit of Utopia (2020) from “From Palestine With Art” by Palestine Museum U.S. Courtesy of the artist.

Srouji praised the show’s organizer, the Berlin-based South African photographer Adam Broomberg, as a long time “ally for Palestinian Liberation.” She added, “it shouldn’t really be on us [Palestinian artists] to ask people for spaces to show because, honestly, we don’t have the capacity. Thankfully, Adam was the person who applied for this. What solidarity really looks like is giving us space for our voices to be heard.”

With a particular focus on topography, the show will also feature “Anchor in the Landscape,” a series of photographic studies of olive trees in Palestine taken by Broomberg and Rafael Gonzalez. These indigenous plants, which Broomberg called symbols of “the unwavering resilience of the Palestinian people,” have long been targeted and destroyed by Israeli occupation.

A further 23 contemporary Palestinian artists will be given centre stage in “Foreigners in Their Homeland,” an exhibition organized by the Palestine Museum U.S. It was not chosen to be an official collateral event but will instead run as an unofficial event at Palazzo Mora from April 20. “How do you present 56 years of occupation?,” the museum’s director Faisal Saleh said in February. “We have a story to tell and our story is compelling.”