Sigmar Polke, Hermes Trismegistos I-IV, (1995) Installation view at Palazzo Grassi, 2016

Photo: Matteo De Fina; © The Estate of Sigmar Polke by SIAE 2016

A lavish and scholarly Polke retrospective at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice puts the artist’s playful experiments with the moving image center stage, casting better-known work in fresh light. Selected by his children Anna and Georg Polke, a program of unseen 16mm films with an Italian connection was culled from hundreds of hours of footage captured by the artist on his Beaulieu camera in a process he described as “an extension to seeing.”

2016 coincides with a number of anniversaries relating to both Polke and the Pinault Foundation, an exhibition rationale that even director Martin Bethenod appeared to find embarrassingly arbitrary as he announced it at the opening. It’s 75 years since the artist’s birth, 30 since he won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, 10 since the opening of the Palazzo Grassi, and—unspoken, but let’s bung it in here anyway—the year of Francois Pinault’s 80th birthday (21 August, should you wish to send a card…).

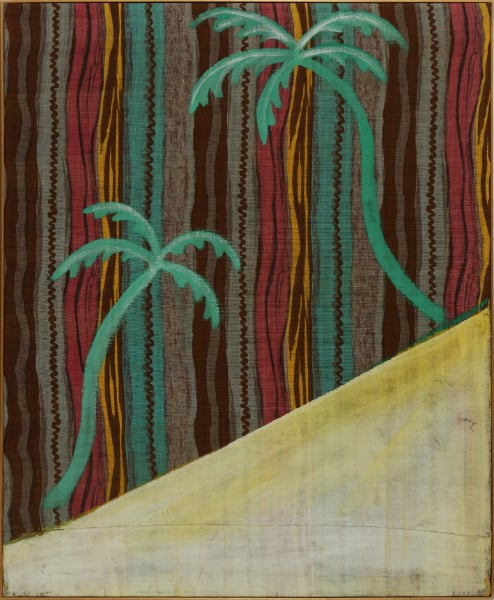

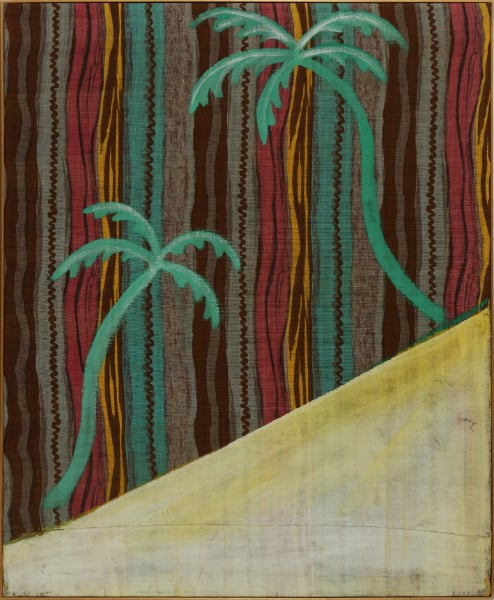

Sigmar Polke, Das Palmen-Bild, (1964).

Photo: Alistair Overbruck; © The Estate of Sigmar Polke by SIAE 2016

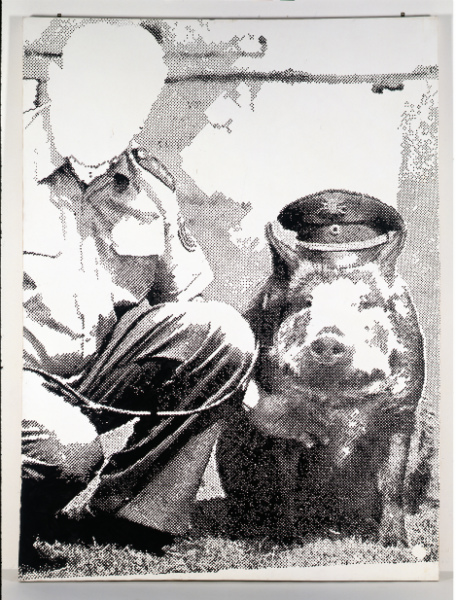

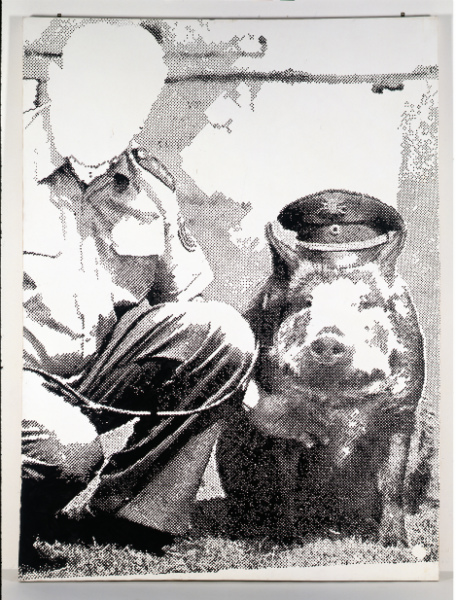

The one commemoration that mattered on that list is to be found at the spiritual heart of this retrospective: Athanor, Polke’s transformation of the German Pavilion in Venice in 1986. Drawing its title from the alchemist’s furnace, Athanor marked an alchemical turn in Polke’s work. It brought together raster paintings engaged with the contemporary world—Polizeischwein and Hände (vorm Gesicht) (both 1986)—with resonant objects (meteorite and rock crystal), vast paintings in resin and pigment, and a light-sensitive wall work.

Of Athanor’s many components, however, only the raster paintings are here physically present. The introduction of Polke’s own films of the creation and reception of Athanor are thus co-opted in part to facilitate a portrait in absentia.

Sigmar Polke, Polizeischwein, (1986).

Photo: Wolfgang Morell; © The Estate of Sigmar Polke by SIAE 2016

Polke’s home movies by no means abide by the obsessive and po-faced archival urge of the artworld’s current generation. Interspersed with footage of the work and wider Biennale, we see Polke, his partner, and assistants goofing around. Filming visitors responding to the exhibition the camera lingers overlong on the T-shirt frontage of a bra-less young woman. There are glimpses of Polke the man, then, but in these Venice films—and the wider moving image program—there is also unexpected insight into Polke the artist.

Polke’s fascination with the transformative (and unpredictable) power of light, with the lenslike qualities of resin and thick acrylic gel, with iridescence, and with spiritual links between the “magic” of captured and moving images and the “magic” of alchemy, all feel to be strongly rooted in his private film practice. It is in his layering of images and effects, however, that the film works feel revelatory.

The multiple-exposure was a mainstay of Polke’s filmplay. He layered travel footage with documentation of his working process, details of pigments and color, exhibitions and monuments, and even material shot from the TV. This complication and dispersion of the image, and rejection of hierarchy between the inherent form of raw materials and the depiction of personal and political themes finds direct parallels in his work with paint and associated materials.

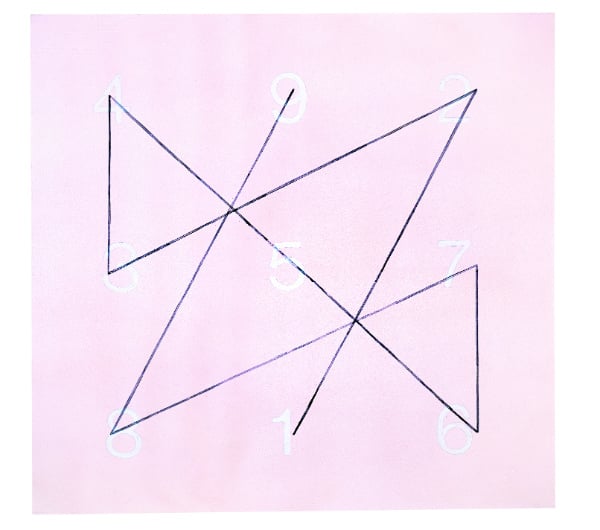

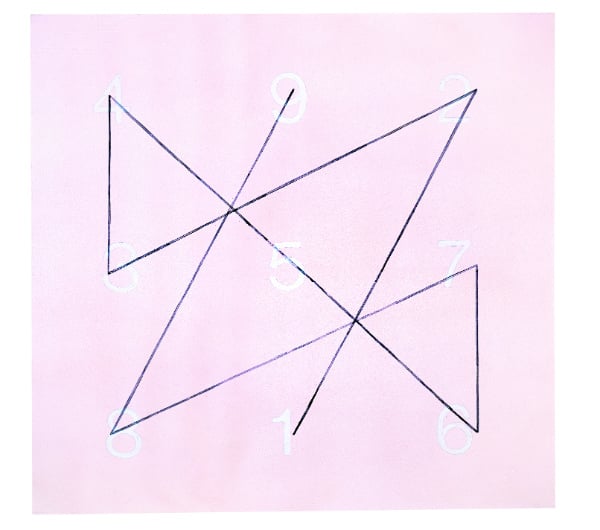

Sigmar Polke, Magische Quadrate I: Saturn, (1992).

Photo: Fridtjof Versnel; © The Estate of Sigmar Polke by SIAE 2016

Since the mid 1960s, Polke’s painted images—often themselves broken up into a grid of raster dots—have co-existed with the more or less assertive pattern and texture of their fabric supports. Early examples shown here include Bohnen (1965), in which the titular green legumes are painted onto an eroded scrap of tablecloth, and Das Palmen-Bild (1964), palm trees on a sandy slope that reap further banality by association with a stripy cloth backing that might have been pulled off a suburban couch.

The imposed overlayering of image on pattern worked to different end in more worldly later works. In Flüchtende (1992), the domestic associations of the patterned support used for a rasterized image of two refugees evoke thoughts of home and the impact of its removal.

Around the time of Athanor, and through to the end of his career, Polke explored the optical, (and spiritual) properties of rare and costly pigments, including the magisterial purple extracted from sea snails and the true ultramarine of Lapis Lazuli. As with his experiments in 16mm, however, Polke’s probing of optical effects also extended to cheap thrills, including the use of iridescent polyester fabric supports (Hermes Trismegistos I, 1995), interference color (the Magische Quadrate series, 1992), and even glitter glue (Indiana mit Adler, 1972).

The perceived link between alchemy and early experiments with moving image are explored in Polke’s Lanterna Magica works, such as Die Geschichte vom Hund (1988-92) a series of translucent, double-sided resin-daubed paintings animated by light. Handsomely displayed in a scarlet cabinet, Die Geschichte vom Hund tells the story of Mother Hubbard – itself a tale of transformation in which an old woman’s dog acquires the characteristics of a gentleman companion – through images from nineteenth century woodcuts.

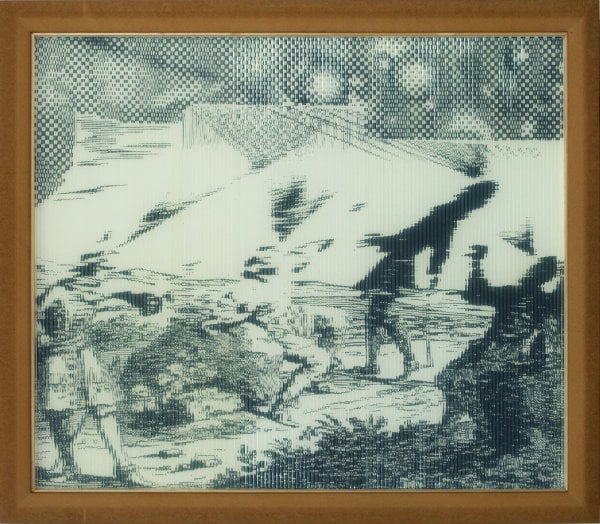

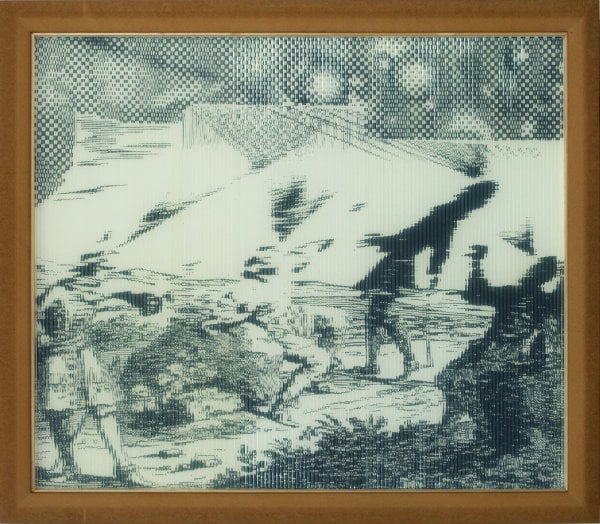

Sigmar Polke, Strahlen Sehen, (2007)

Photo:

Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen; © The Estate of Sigmar Polke by SIAE 2016

Of all Polke’s experiments with the passage of light – including the handmade lenticular images of the 2007 Strahlen Sehen series – this exhibition suggests the seven vast Axial Age (2005–7) paintings as the most important, thanks to a radical (and courageous) positioning choice. In contrast to the unobtrusive brick of their familiar position in the Punta della Dogana, here the works (the largest of which, Deucalion’s Flood, is 900 x 480cm) are shown on custom supports that stand proud of the Palazzo’s walls, and, more importantly, its windows. Thusly positioned, these works, with their resinous, mercurial surfaces coruscating with iridescent purples and golds, are revealed to be not canvases but transparencies, painted on gauzy polyester that leaves nothing but the illusion of unstable color floating in sunlight.

Sigmar Polke is on view at Palazzo Grassi, Venice from April 15-November 6