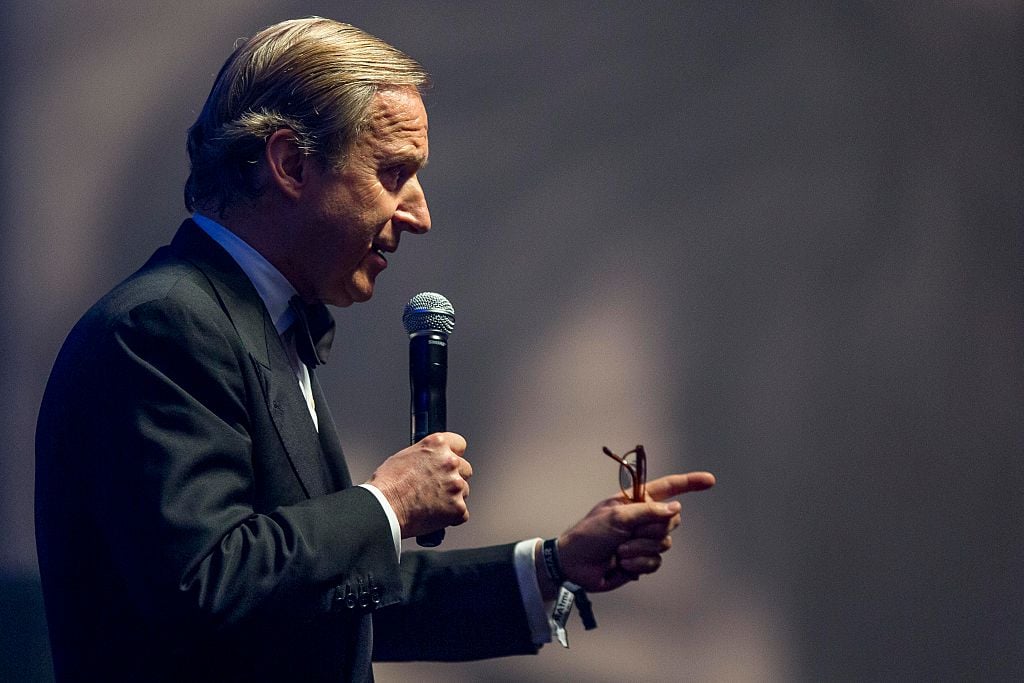

HONG KONG – MARCH 14: (EDITORS NOTE: This image has been converted to black and white) Auctioner Simon de Pury attends the Gala dinner as part of the 2015 amfAR Hong Kong gala at Shaw Studios on March 14, 2015 in Hong Kong. (Photo by Jerome Favre/Getty Images)

Simon de Pury’s autobiography, The Auctioneer (St. Martin’s Press, May 2016), in which he recounts how he became the world’s pre-eminent auctioneer, begins in medias res and in ardor: “If anyone needed a rebound, it was I.” The year is 2002 and Phillips de Pury is going down the toilet. Quebequios billionaire Louise MacBain arrives both as de Pury’s romantic and fiduciary savior, but by page two, “that love affair had gone the fiery way of the Twin Towers.” This memoir is as snappy and swaggering as the prestissimo speech acts the author is world famous for performing with gavel in hand.

From this personal nadir, we rewind to where it all began. De Pury, as most people in the art world know, was born in Switzerland—Basel, prosperously. He clarifies that his aristocratic airs are firstly the product of nature rather than nurture: “My father was a baron, though that was a title he kept in the closet (Just for the record, I’m one, too, and I keep my title in the closet as well. Self-effacement runs in the family).”

Other family secrets now evidently out in the open are that the town square in Neuchatel, Place de Pury, was named for the De Purys, as well as a failed colony in South Carolina called Purrysburg (which is not a cat amusement park).

A true citizen of the world, who even spent a chunk of his childhood living in Tokyo’s Okura Hotel with his parents, De Pury paints his own character as quintessentially European, in that he is, if nothing else, a man of his passions. His path to art is a lifelong roller coaster of arousal, suffering, ecstasy, despair, and capitalist vindication: internal ups and downs only tempered by his eventual ambidextrous indoctrination into the New York art world, which he describes—in dichotomy with the old world—as principled on opportunism and bottom lines.

Decades before this, New York is where he had the door slammed in his face as a portfolio-carrying teenaged artist. Decisively having retrained his sights on ascending the ranks of Sotheby’s auction house, De Pury traces his movements around Europe from generalist intern, to Sotheby’s trainee, to neophyte furniture department auctioneer, to up-and-coming modern and Impressionist powerbroker by the age of 25. These coming of age chapters hinge on a plan hatched by family friend Ernst Beyeler, the legendary collector, who poses the life-defining question, “Is your attraction to art physical or intellectual?”

Simon de Pury and Michaela de Pury. Happy Hearts Fund Gala 2012 “Land of Dreams: Mexico”. Image: Patrick McMullan

Beyeler portends that De Pury’s answer, the former, means he must never become an academic or, as in a Disney curse, he would live a life of vicariously staring at slides, never to see, touch, or own a masterpiece himself. In this way, Beyeler devises a plan for De Pury to briefly intern with Galerie Kornfield in Bern (an auction house better known as a top-flight prints and drawings dealer) and then continue his apprenticeship in London at Sotheby’s under Derek Shrub (and, several months later, Peter Wilson, the auctioneer De Pury describes as his role model.)

Throughout the book, more words are probably given to descriptions of women than art, though its heart beats with the reminiscences of one true romance (however platonic), and that is with a man. Soon after setting up Sotheby’s Geneva outpost in 1975, De Pury is recruited by a colleague to become the curator for Baron Hans Heinrich Agost Gábor Tasso Thyssen-Bornemisza. He moves into Thyssen’s lakeside guest house in Lugano and begins a peripatetic existence at the behest of a man around which the highest echelons of the international art world orbit.

5th November 1956: Baron Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza (1912 – 2002) lights a cigarette for his new wife, British fashion model Fiona Campbell-Walter, whilst staying at the Ritz Hotel in London. The couple were married six weeks before in the Italian village of Castagnola. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

This middle-third of The Auctioneer is where it flies, as a personal document and a historical one. The most enjoyable, and creative, aspect of the book is the gloriously immoderate name-dropping of people, places, and other signifiers of extravagance, much of which takes place while in the employ of “Baron Heini.” This takes on a poetic, schizophrenic life of its own, exquisitely rendered as equally farcical and obscene:

“Then an Indian princess in Montreux introduced me to her fortune teller.”

“She then sold the Holland Park house to Goga Ashkenazi, a world-class adventuress connected to the ruler of Kazakstan.”

“If I fucked myself out of the gatehouse and into the villa proper, I also ate myself out of Grieves and Hawkes and into Caraceni.”

“Back on terra firma, the baron assuaged his vertigo with Forbes’s then-inamorata Elizabeth Taylor.”

“Qatar is the Florence of Arabia, and its Sheikha Al Mayassa, at 31, the sister of the Emir and a worldly Duke graduate, is a desert Catherine de Medici.”

“Our star client Rosemarie Kanzler, who was also from Zurich, but from the wrong side of the Hauptbanhof, had become a singer in Berlin on her way to wealth and had serenaded Hitler to sleep with Viennese lullabys.”

“Few fetes could compare to her 1986 birthday bash for the prince, where the birthday cake was festooned with sixty phalluses made of marzipan, and the people who ate them included Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall, Al and Judy Taubman, Malcolm Forbes, Adnan Khashoggi, Ann Getty, and of course Heini and Tita.”

MIAMI BEACH, FL – DECEMBER 03: Simon De Pury, Daniel Arsham, and Swizz Beatz attend the ArtNet & Whitewaller Panel At L’Eden By Perrier-Jouet at Penthouse at the Faena Hotel Miami Beach on December 3, 2015 in Miami Beach, Florida. (Photo by Andrew Toth/Getty Images for Pernod Ricard USA)

“With that privileged access to the Vatican, plus an eyebrow-raising love afair with her Italian counterpart princess Alessandra Borghese, whose mother was heiress to the San Pellegrino water and Citterio prosciutto fortunes, Gloria had moved to Rome to be with her new passions.”

Delirious depictions of class are the book’s greatest strengths and weaknesses. It’s illustrative to see here, years before “globalization” had metastasized, how people and places bear metonymic bonds with one another. These royals and scions are the embodiments of the cities and countries they represent, insofar as they are the vessels through which sovereign power and wealth are merged, consolidated, and passed down through generations.

However, De Pury almost seems to playfully troll the mass market readers for whom the book is intended with infrequent but eyebrow-raising asides about the have-nots that seems to simultaneously poke fun at the insulation of his own class of haves. The first person described as coming from an “underprivileged” background is his first wife, Isabel, whose father, rather than a major collector, is merely a knighted chancellor of Essex University. And in one of the more tragic sections of the book, in describing his greatest failures at auction, De Pury recounts doing a charity benefit for Parkinsons disease in Neuchatel. After realizing that “most of the attendees were victims of Parkinson’s and, on top of that, were people of very limited means,” he calls the resulting lack of sales heartbreaking. “There was no way I could use my skills to part these people from assets they did not have,” he writes. “I couldn’t have gone home more depressed.”

Simon de Pury and Leonardo DiCaprio at the fundraising gala for the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation in St Tropez, France. Image: Getty Images

One last anecdote like this takes place in the book’s penultimate chapter, “Courting Medicis,” which confoundingly progresses from a bonafide Medici number one (Sheikha Al Mayassa of Qatar) to a Medici number two who is quite dubious by comparison: Leonardo DiCaprio, adulated as a visionary collector for almost two pages. De Pury asserts the fact that 650 people paid 12,000 euro each to attend a Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation auction held in St. Tropez last year “is testimony to how big—and how generous—the oft-derided ‘1 percent’ actually is”—as if more than the very richest minority of the 1 percent can afford 12,000 euro tickets to a fundraiser, and as if generosity if the common bond among the Riviera groupies of “the pussy posse” (those are the media’s words, not De Pury’s).

It’s interesting that De Pury studiously avoids quantifying his own wealth in any form. Price tags abound elsewhere, but even when he narrates being on the opposite side of an auction block for a lot of Karl Lagerfeld’s Jean Besnard vases—“These vases, I vowed, would never escape me”—he never names figures as “the prices became astronomical” in a bidding war with a mystery opponent (later revealed as a spurned Louise MacBain).

Overall frank, confessional, entertaining, and well-written (with co-author William Stadiem), the book begins to unspool in its denouement, in which De Pury muses on the future of art and describes his new online venture akin to a higher price-point Paddle8. This sales pitch fizzles following the champagne fizz of his outlandish memoirs.

In closing, he comes full circle to a defense of potential misgivings about his stock. “I always saw myself,” he writes, “as an artist in a dealer’s suit.” I’m not sure if he has met the reserve for that claim, but it’s fair to say that Simon de Pury’s life story sells itself.