People

‘The Colonial Effect on Us Is Huge’: Why Congolese Collector Sindika Dokolo Sees Restitution as a Way to Remake African Identity

The Congolese mega-collector is on a quest to help return illegally looted art to Africa.

The Congolese mega-collector is on a quest to help return illegally looted art to Africa.

Kate Brown

The question of whether Western museums should return works of African art to their home countries is vexed and hotly debated. But the mega-collector Sindika Dokolo thinks there’s a simple question that should be driving restitution determinations today: Was the object obtained legally?

The 47-year-old Congolese business magnate has used this query as the basis for a worldwide campaign to compel Western museums, art dealers, and auction houses to return Africa’s art in cases where it was not legally acquired. Five years on, he and his international team of art sleuths have tracked down and overseen the return of 15 significant works of art.

Dokolo is himself an established collector of African art. He began collecting at the age of 15 and, as part of his Sindika Dokolo Foundation, has since amassed upwards of 3,000 works, including those by some of the continent’s most important names: Zanele Muholi, Yinka Shonibare, and William Kentridge. Dikolo is happy to lend out works from his collection, but interested institutions had better first read his manifesto and know that they must agree to stage a show of similar content and value in Africa.

We spoke to the collector and philanthropist as he was waiting to board a plane to Brussels to meet the Congolese ambassador to Belgium to officiate the return of another work. He weighed in on the nuances of the African art market, the restitution debate, and how he’s trying to stir the pot by playing by the rules.

View of a gallery of “mugshots” of missing African artworks. IncarNations. African Art as Philosophy (2019). BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts.

At the exhibition of your collection that you co-curated at BOZAR in Brussels, there is a room of “mugshots” of African masks that you and your team are looking for. What happens if and when you find a missing work?

We have a team in London and Brussels that have been working for the past five years to identify original pictures with series numbers from museum archives so that they can prove the piece belonged to the museum. Then, we research pictures of the piece to determine the last time it was seen somewhere on the market so that we can try to follow the lead and find the pieces in collections.

We confront the current owner and we offer them two options: Either we go to court based on the evidence that we have, which means reputational damage, or we pay an indemnity, which is not the current market price but the price they paid when they acquired it. I tend to presume that the collector bought it in good faith.

We always try to hold a repatriation ceremony This whole process is also a way for us to raise awareness within the African public. I am very concerned with the principle that you can never be stronger outside than you are inside. What does the African public make of the repatriation debate? Are we using this debate to better understand how crucial it is for us to re-learn our own history and re-discover ourselves, our values, and our artistic creation? It is important that we, within Africa, look at this art in a dignified way so that we understand how important our contribution is. Some young people still think this art is a sign of witchcraft or savagery.

So you find that young people have internalized colonial ideas about their history and its objects?

I would guess that if you did a survey today, at least in Angola, very few would consider these art objects to be art or understand the value that it has. The colonial effect on us is huge. We look at our own self, at our own history with so much exoticism.

There is a lot of work that needs to be done and it is not a question of aesthetics, it is much deeper than that. It is political. We are not the owners of our own gaze. The presence the other is still very strong. Being African today means reading your own world through someone else’s eyes. So this whole debate around restitution is a huge opportunity to address this issue and to work on it in a constructive way. We want to take away the veil that the colonial time has left on us.

View of IncarNations. African Art as Philosophy (2019). BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts.

Were you encouraged by the restitution report published in France that advocated for the return of many African objects currently held in European museums?

This initiative was completely mind-blowing. Yet one year later the French have not done anything substantial. Now, if you look at Germany and the Netherlands, they did not make the same fuss or conduct all this advertising, yet they began to take some concrete steps.

And so while I thought the report was interesting, I am more interested at this stage in the African agenda by itself than in the evolution of the European perspective. I try to develop as much as possible an Afrocentric approach to what I am doing, especially in culture.

View of IncarNations. African Art as Philosophy (2019). BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts.

Speaking of the Afrocentric perspective, there have been several new museum projects on the continent, such as the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar and a planned museum in Kinshasa.

I know more about the museum in Kinshasa because I just found an important Kuba mask that I will return to that museum, which will be my first repatriation in the country. I want to organize a proper ceremony in Kinshasa in the presence of the Kuba king, who is very impressive. Do you know that picture of Picasso dressed as an African king? There was an image of it in an exhibition at the Quai Branly. It is actually a collage done by one of Picasso’s friends, but actually this collage was of the full attire of the Kuba king. It is spectacular.

What do you think about the funding of these museums? The Kinshasa museum is being funded in part by South Korea, and the museum in Senegal by Chinese investors.

When you are a bankrupt country everything is funded from outside and this fact does not only pertain to Africa. I am thinking about Portugal and Greece. These countries were bankrupt a few years ago and were funded by other countries, and that was no problem. Why is it a problem for Africa?

My country lives in a state of virtual bankruptcy. We cannot secure the integrity of the territories, educate children, or build roads. So the problem is not where the money is coming from at this point, the question is how to make the best of the little crumbs that we manage to get here and there. In terms of South Korea helping the Democratic Republic of Congo with a museum, I don’t see a polemic there.

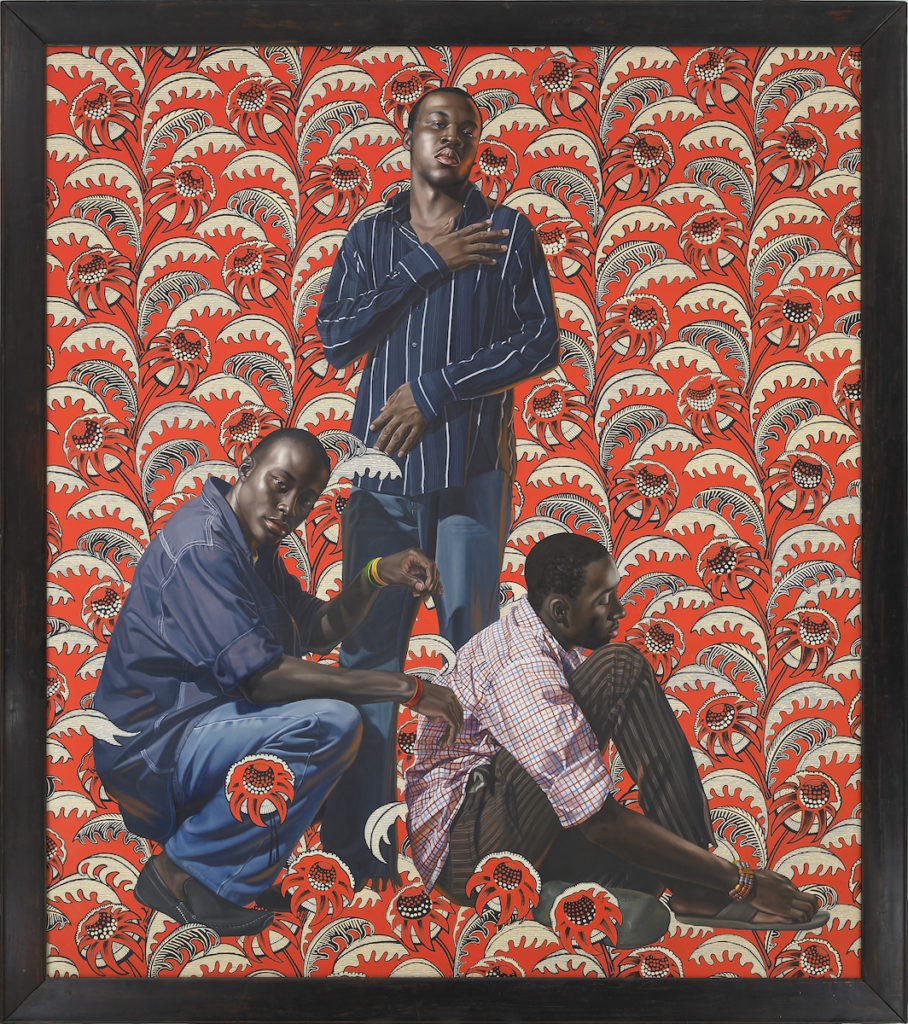

Kehinde Wiley, Hunger (2008). © Kehinde Wiley. Courtesy of Deitch Projects.

But once the museum is open, how can it thrive? There are numerous instances where impressive museum projects fail due to poor long-term planning.

Yes, the question will be how we, as Congolese, will organize ourselves, because we did not really manage to yet understand what a museum is. It is not just a building. It is a cultural operator. You need to have curators and professionals who are linked to museology. This is where we got it wrong so far: We understood it first as a show-off building and then we saw it as a state company where we could thank people by naming them there. I am not criticizing it because I am not aware of all the details, but I am aware that it has been a problem in the Congo before and it is a problem in Africa that we do not always promote the right people. A lot of people do not yet understand that a museum is as complex as a nuclear facility—it requires people who are trained.

All that is not the problem of the South Koreans, that is more a problem for us as an African country. It is exactly the same issue as with the question of repatriation. What do us Africans do about the possibility that maybe some of the most important treasures in the world might come back to us and come under our responsibility? Do we take the necessary measures? Are we training the right people? Are we getting prepared? I think we are missing sometimes the dimension of how critical this is. We still consider that as aesthetics or a tourist opportunity. We do not fully understand the strategic and political dimension of art and culture. So this is a bit of the work we are trying to do as well, to raise this awareness.

As an avid collector, what do you make of the big boom in the contemporary market for African art?

As much as I criticize the contemporary art market in general right now, which I think is full of second- and third-degree concepts and aesthetics, not to mention a lot of emptiness and absence of ambition, I see that in other parts of the world it is the other way around. In bankrupt African countries, which are at a crucially strategic time in their existence, there is so much important cultural production there to expose to the public.

I always give the example of South Africa. Within my contemporary collection, which includes Sue Williamson, William Kentridge, and Kendell Geers, I am very interested in the Rainbow Nation era that marked the end of apartheid. At this very crucial time in the history of that country, if it hadn’t been for the artists who managed to dream this utopia of a rainbow nation, it would have been impossible to realize. There is an important role of art and culture and artists that goes way beyond the question of aesthetics.

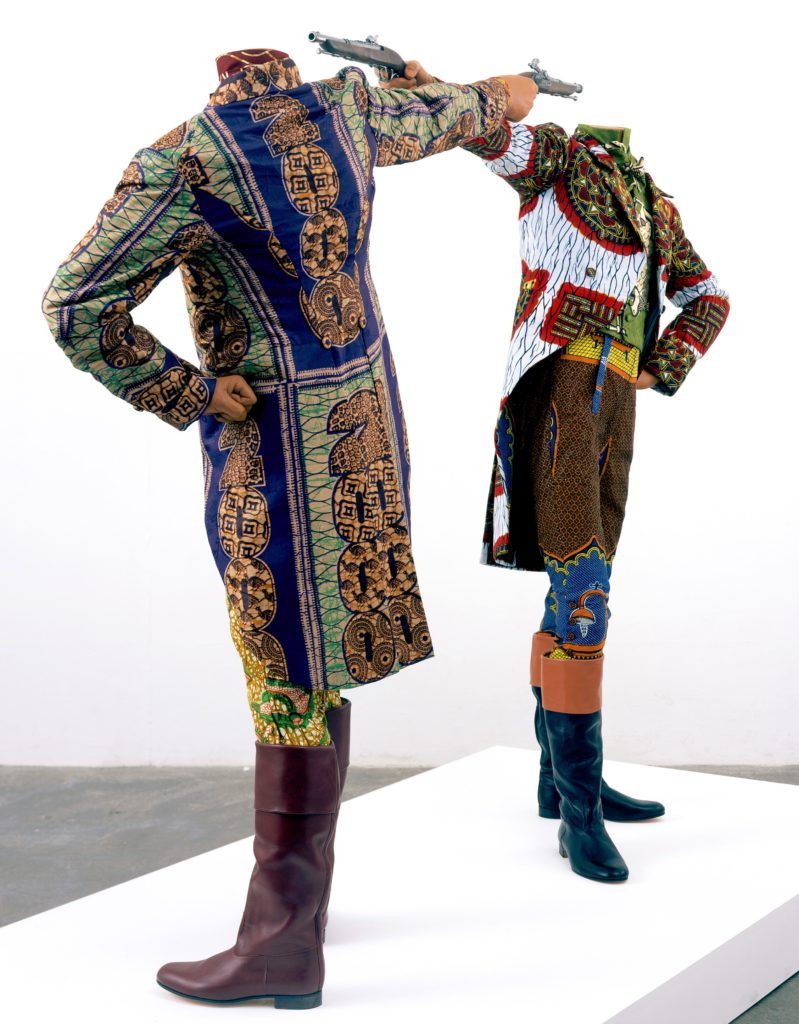

Work by Yinka Shonibare.

What do you think the next steps will be for the African art scene?

The next challenge for African art will be to develop an internal market. We are one of the places on earth with the biggest growth; we have everything we need to develop an art market. We have an exploding middle class, a class of industrialists and others who could become patrons. What we have not been successful at is getting African collectors interested in Africa. The artists that I am in contact with are not as eagerly collected within Africa as from the outside. Take Yinka Shonibare, for instance—I think I am one of the only African collectors that collect him. This is a real challenge. However, all this debate about historic art and how strategic, political, and beautiful it is, will contribute in time to generate a new collector scene.

Even Chinese art and Russian art, it began as a trend because it is first of all collected by Chinese and Russian collectors. The next big challenge will be to see how many collectors we can generate and I am not very happy with the way this is going.

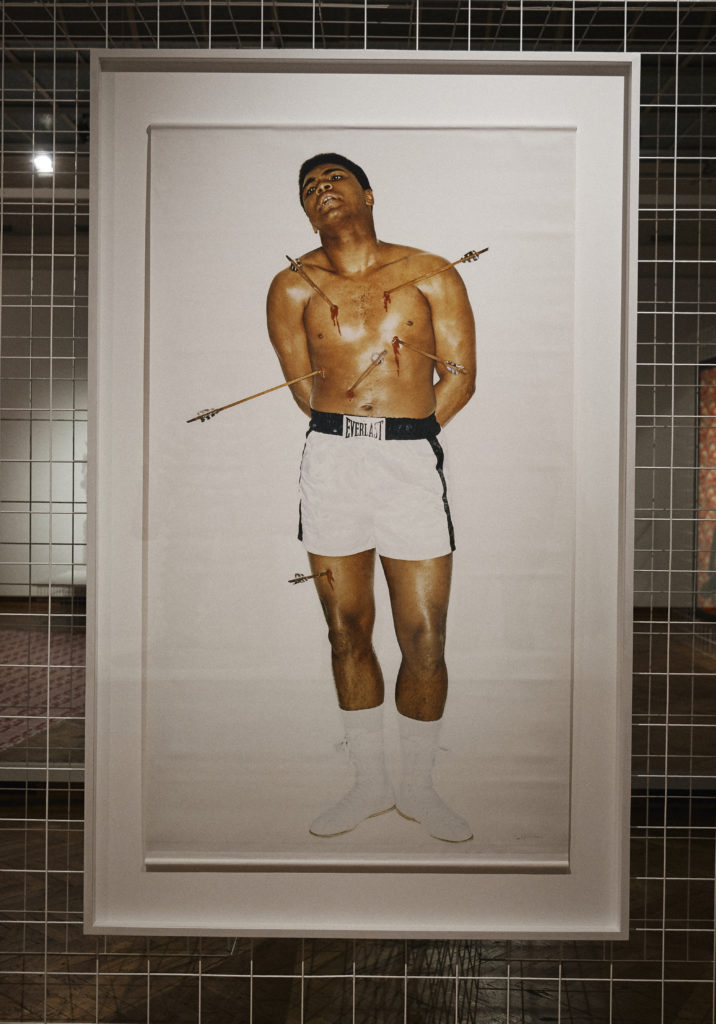

Chokwe Mask that went missing from the Dundo Regional Museum in Angola during the civil war (1975-2002). The mask will be returned to the Angolan authorities after the exhibition at BOZAR – Centre for Fine Arts.

There has been a surge in new art fairs focused on African art. Could fairs be part of the solution?

Art fairs could be a critical player, but dealers will only come back if they sell. That is always the problem. How do you trigger the interest to start with? It is taking a long time. Fairs like 1:54 are such amazing initiatives, there is a lot of quality and dynamism. But it is a lot of foreign people. I am not feeling the African art market yet. I have a lot of friends who are prominent business people in Africa, but somehow I have not yet managed to convince them to buy.

Are you concerned that a similar situation could recur, where African art is again owned by foreigners and held abroad?

There is a clear parallel between the two, but contemporary artists need to be exhibited, and they need to be bought, and they need to live, so it is different. The problem of ownership is not the main issue, the main issue is access. There are a few artists who have managed to be active on the market and do well in big institutions and the art market, but who also make sure that their work is present and visible on the continent. Ownership by African collectors is great, but it’s more important that it is being seen by the public.

View of IncarNations. African Art as Philosophy (2019). BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts.

African art has been a major inspiration to many modern artists, including Picasso. What can traditional African art teach contemporary artists today?

African civilizations were so much more advanced than we are today in terms of the role of the artist and the artistic proposal. Take performance art, for example. We are reaching now the limits of what the art market can do. You cannot essentially own performance and yet it has value, and we are encountering this question in a major way right now. Selling it is ridiculous, so we need to perhaps rediscover the way this medium of art intervened in pre-contact societies to understand how it can really revolutionize the contemporary art market.

You stipulate in loan agreements that part of working with your collection means that foreign institutions need to establish a parallel exhibition on the African continent. Some have not yet panned out, but you have IOUs from several institutions or curators in Europe.

Anybody who is interested in artworks or in exhibitions of the collection, I am very happy to do it, but I have a few conditions. The first condition is that I do not accept any money because I know that the hand that gives is always on top of the hand that receives. It is also important that whoever I work with understands that my collection is contemporary art. I will loan the works for free, but you have to do everything in your power to organize the same exhibition somewhere in Africa, whether it is in a museum in Johannesburg or on a baseball field in Mogadishu. You cannot just show African art, you have to get involved. It has not always been successful, but we are trying in this way to have more activity on the continent than abroad.

We need to start looking at Africa as something other than mass defeat. The access to art and creativity is what makes us human and garners respect, and if I can read respect in your eyes, that is a way that I can elevate myself and a way that I can take care of myself. This is what lies behind the collection.